Romaphobia is one of the last acceptable forms of racism. It is acceptable in as much as it is palatable or understandable given the overwhelmingly negative attitudes towards Roma across Europe. Recent research by the World Bank explored social exclusion and attitudes towards certain groups in society with Roma communities across Europe, even generating negative attitudes comparable to paedophiles and drug takers in some states.

It is important to understand why this is the case. Romaphobia is present in casual conversations in homes and at work, in media portrayals of the carnivalesque Gypsy, when state authorities accuse Roma of abducting blond-haired, blue-eyed children, in the town planners who place Roma in ghettos, in political elites who target Roma for special treatment and bulldoze their homes, when authorities segregate Roma school kids from their peers, or deport Roma communities en masse.

Where does Romaphobia come from?

There are several reasons that might explain why Roma are stigmatised. The first is exclusion. For centuries, Roma have been excluded from nation-building exercises promoted by political entrepreneurs, their difference harnessed as fuel to build the nation as ‘us’ (the majority) not ‘them’ (Roma). Roma, as a heavily constructed and policed identity, become necessary ‘others’ positioned outside of the nation. Roma then become easy targets for political elites who want to bolster their own popularity and power. An example of this is seen in Hungary with Roma culture and identity consistently equated with criminality by media and politicians.

Over time a stigmatised identity becomes shackled to the internal ‘other’, and proves almost impossible to escape. Usually a stigmatised identity becomes so rooted in everyday language and practice that it becomes self-sustaining: Roma who are stigmatised as impoverished and helpless cannot get work and may end up on the streets begging, meaning that stereotypes are confirmed.

This Romaphobia ‘loop’ is fuelled by distrust and a lack of understanding between the majority and Roma communities. Changing the hearts and minds of the majority is made more challenging by the presence of Romaphobic statements made by political representatives, the persistence of entrenched negative associations of Roma/Gypsy identity in everyday discourse, as well as the inability of Roma communities to effectively break these stereotypes. In Italy and France, for example, elites have actively targeted Roma communities, creating a narrative which maintains that Roma are not part of French or Italian societies even though Roma have lived there for over 500 years.

Another reason is avoidance: some Roma want to avoid the enveloping arms of the state and create opt-out strategies to actively resist incorporation into society. The ultimate aim here is to retain control over one’s own affairs believing that survival cannot be left in the hands of others. For a community which has been persistently persecuted, such a strategy is understandable. However, this oversimplifies the story as many Roma actively participate in societies across Europe.

A question of solidarity

Stereotypes, unless challenged, will remain. There have been groups in the past which have protested negative ascription of group identity such as women, African Americans and gays and lesbians, to varying degrees of success. Roma too have mobilised over time in different ways including transnationally with the creation of the International Romani Union, International Roma Day, as well as recently with Roma Pride parades, demands to be included in Holocaust commemoration, and the newly established European Romani Institute for Arts and Culture. These outward facing interventions are absolutely crucial as they demonstrate the capacity to articulate a positive Roma identity and create a dialogue for inclusion.

In the past, we saw efforts to assimilate Roma communities by the state, to dilute Roma identity to the point where Roma lost their cultural specificity. Today we see Roma communities targeted by populist forces who spotlight the presence of Roma as being unwanted or threatening. Across a continent still reeling from economic collapse, Roma communities are a convenient scapegoat for social and economic problems. In reality more participation and visibility, not less, is the answer. The mobilization of Roma communities in fields of culture, politics, and economics is the best way to declare belonging to society, to change the narrative of Roma stigmatization and demand rights to be included in society as equals.

The conviction that Roma are Europe’s perennial outsiders has become a trope and, whilst useful in order to understand the historical exclusion of Roma, it does not preclude the possibility of Roma agency and change in the future. By articulating demands for equal rights, it challenges the notion of Roma as the archetypal other and enacts the citizenship of Roma across Europe.

It may take a generation to start to see significant results, and it is unclear exactly what these successes will look like but Roma communities are determining their future through participation and representation. The public voice of Roma is often ignored or silenced and Romaphobia can stifle this voice or distort its message. That is why efforts at Roma mobilization at the local, national and transnational levels need to be supported. And why challenging the prevalence of anti-Roma prejudice requires mobilization in political, cultural and economic life.

Whilst the voice and visibility of Roma across Europe can challenge negative stereotypes, it is necessary to ensure interaction and inclusion between Roma and non-Roma, finding common ground as people who want a just, equitable and better life. It is only through the mobilization of Roma communities that manifestations of Romaphobia can be challenged, institutions underpinned by Romaphobia broken and political practices motivated by Romaphobia halted.

*The lead image in this piece is an artwork by Damian LeBas. All rights reserved.

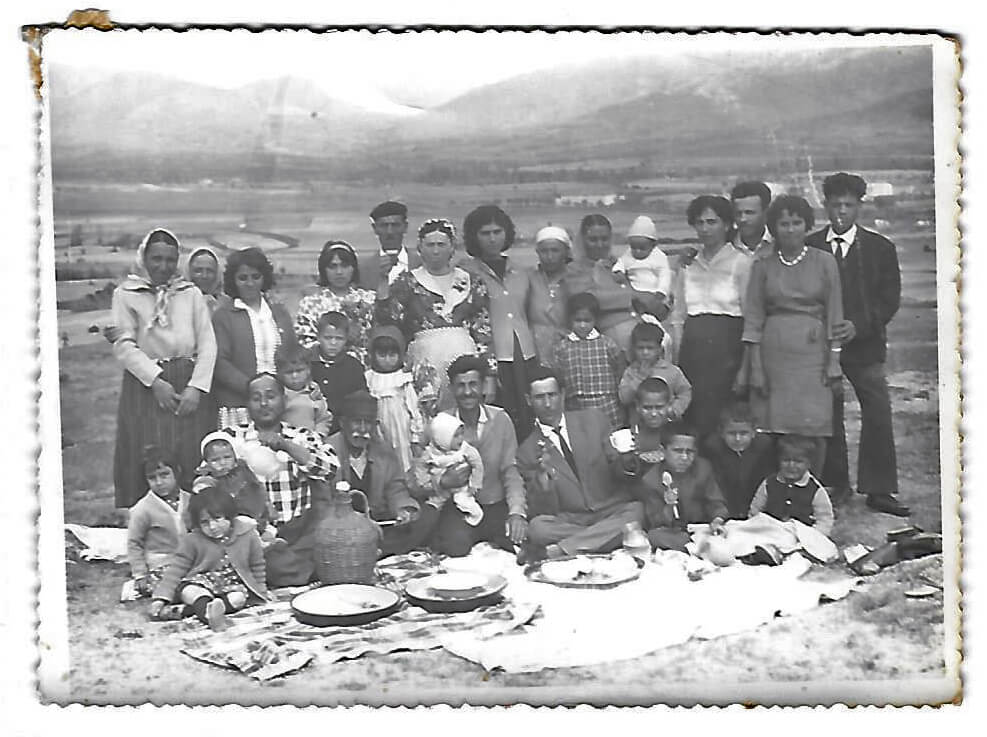

** The images in this piece are published with thanks to #RomaReality, a group which collects “photos of Romani people going about their daily lives without the exoticizing filter of mainstream media and academia.”

***Aidan McGarry is the author of Romaphobia: The Last Acceptable Form of Racism. Available to purchase here.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

Speaking and writing about “antitsiganizm” has become a kind of fashion – at

least in Germany. Projects and jobs are often connected with that. Therefore

McCarry is just following this fashion – nothing new under the sun.

In nearly all these “antitsiganisticist” oeuvres one aspects is excluded: the

component Gypsies themselves contribute to their negative image. I know, such a

remark is considered “antitsiganistic”, but uttered by somebody who

knows Gypsies for nearly 40 years.

Denying this component reveals a lack of objectivity on one side and is suitable to strengthen the aversion against

Gypsies among those people who have had negative experiences with Gypsies.