“A small society, a big family. That’s what we are.” Alì, dark eyes and a proud look, is washing vegetables for lunch. He arrived in Greece from Afghanistan more than one year ago, in March 2016, and he never thought he would become part of a community project that involves cooking, too. After being in several refugee camps, he reached Athens and began to live in this seven-storey building on Acharnon Road, just metres away from the National Archaeological Museum and Victoria Square: the City Plaza, an old hotel which has become the biggest squat in the city.

The hotel shut its doors because of the dramatic financial crisis, but on 22 April 2016, a group of activists and refugees decided to occupy and renovate it. Its 92 rooms now accommodate about 400 people, half of which are children. Most of the people here are asylum seekers, but there are also volunteers and activists who have come from all over Europe to participate in this grassroots integration experience that is really setting an example. On its first anniversary, the City Plaza celebrated what has turned out to be a winning bet: at the beginning, it was just an experiment of self-organisation to react – after the closure of the Balkan route and the deal between the EU and Turkey – to the refugee crisis in the heart of Europe. Today, it is an internationally acknowledged and studied model.

During these twelve months, the City Plaza has hosted about one hundred families. The majority come from Afghanistan and Syria, but there are also Kurds, Iraqis, and Pakistanis. There is a social-based access criterion: priority is given to people with children or health problems. For this reason, many of the guests have been living in the hotel from the very beginning and are now permanent residents; others have replaced those who left to go further north, also thanks to the European relocation program.

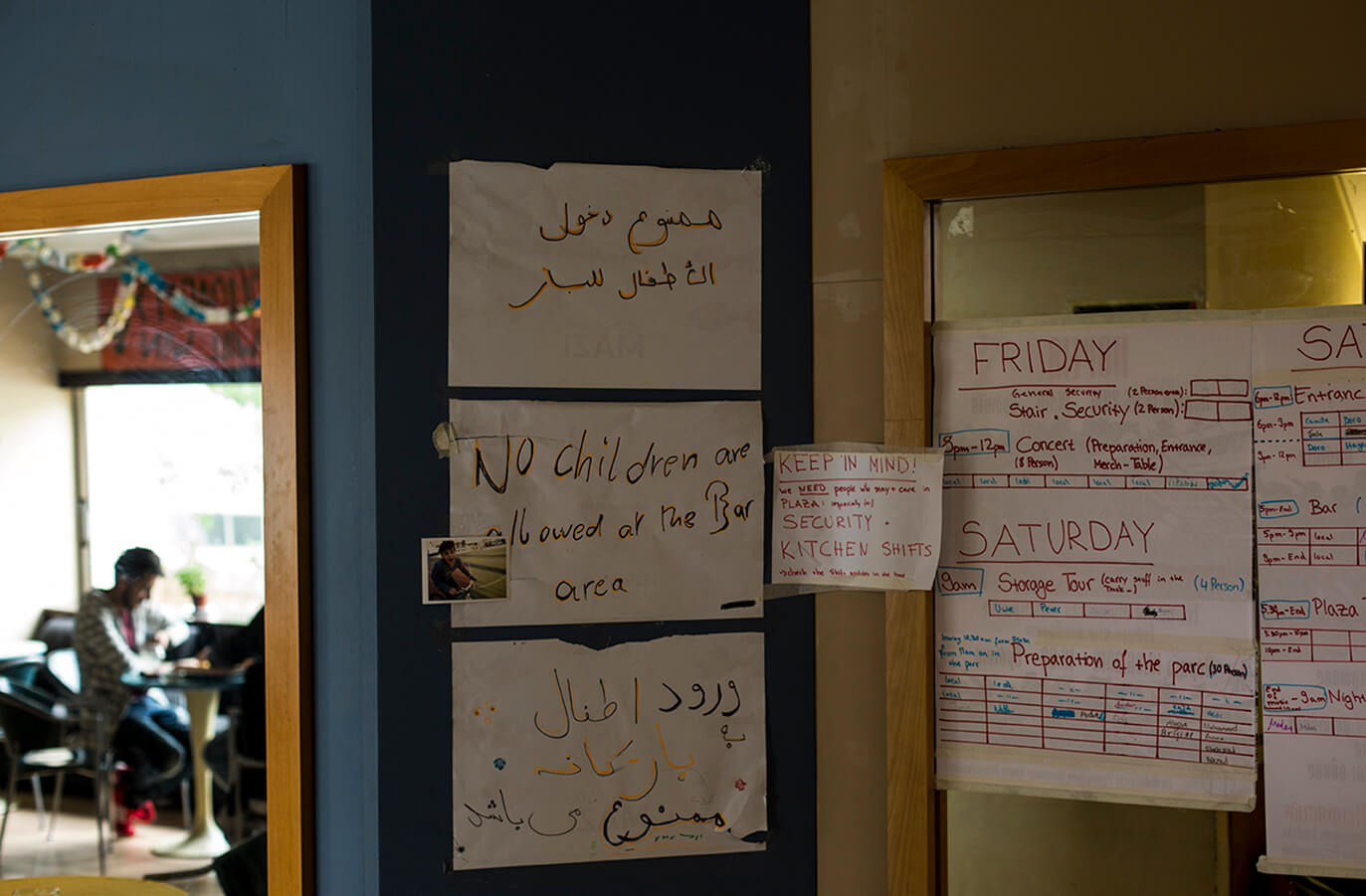

Each family has its own room, but everyone participates in the community project by taking turns in the kitchen (where 800 meals are served every day), in the laundry, or in other services that keep collective areas in good condition. New arrivals are greeted by the squatters at the reception desk, where they receive a registration form they must fill in with their essential data: whether they are in Greece seeking asylum, whether they want to join the relocation program, or whether they are waiting to be reunified with their family.

For the refugees in Greece there is nothing like this place, because here, first of all, we are considered humans.

According to the information they share, they are then assisted through all the legal procedures. A medical team is in charge of medical care. “For the refugees in Greece, there is nothing like this place,” Alì explains, “because here, first of all, we are considered humans. In the camps, it is often too easy to forget that refugees are people. It is different here – volunteers, activists, coordinators, refugees, everyone is cooperating in this big project, which also has a strong political connotation. I am proud of being part of it, chiefly because at the City Plaza we believe in the importance of two aspects: health and education. These are essential rights for people who come from countries where they don’t exist anymore.”

A safe harbour for a long wait

Fatima is from Syria. Sitting beside the window, she looks at her children playing hide-and-seek behind the hotel’s glass walls. She is waiting to join her husband in Germany. She has been stuck in Athens since the closure of the Balkan route and now shares her room with another woman and her twins. “We’re following the procedure and waiting to join him,” she explains. “In the meantime, we found this place where at least our children are fine.”

Her case is not a rarity. According to the latest Unicef report, almost 75 thousand migrants and refugees, including almost 24 thousand children, are currently stranded in Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, and the Western Balkans. Unicef highlights the seriousness of the situation for single mothers and children. “In most cases” the organisation clarifies, “men are the first family members who migrate towards Europe, while the rest of the family follows them at a later date. But with the closure of borders in 2016 and the implementation of the EU-Turkey agreement, many family members are blocked in transit countries where they have to apply for reunification and start a process that can take from 10 months up to two years.”

Today, the City Plaza accommodates about 180 minors, almost half the total number of its squatters. They are the ones who welcome the new arrivals, running up and down the stairs of the large building covered in pictures of their everyday life together. On the anniversary of the occupation of the building, a new children’s area was opened on the first floor, a sort of kindergarten with toys and coloring books, where the French volunteer Clementine keeps an eye on the younger ones. Some babies are just one year old.

Together with Clementine, we meet Vittoria Morrone, a girl who moved here from Turin, Italy, five months ago. The whole sixth floor of the hotel is now occupied by the volunteers who keep arriving from several countries. “After graduating in psychology, I decided to take some time off to understand what I want to do with my life,” Vittoria explains. “I’d heard about this project and thought it could help me. At the beginning, I had planned to stay just one month, but I’m still here.” Like everyone at the City Plaza, Vittoria takes turns wherever she is needed, from the reception desk to the laundry. But for the last two months she has been in charge of the women’s area, which was created to meet the needs of female refugees. “For cultural reasons, many of them spend the whole day in their rooms because they find it difficult to stay in group spaces like the bar,” she says, “that’s why it was important for them to have a private place.”

A yoga and relaxation course is held in the new women’s room, and once a week an Afghan girl gives beauty lessons. What is more, important information about gynecological issues, pre- and post-pregnancy, is available here: “This is their little shelter.” Vittoria also teaches English to a female class: “Some of the refugees have never attended school. Here they have the possibility to learn, and this is extremely important.” Uwe Khorl is 28 years old and comes from abroad, too. He joined the project after taking a medical degree: healthcare is constantly guaranteed in the occupied hotel, “but in case of emergency, I can lend a hand,” he says. “Otherwise, I do whatever is necessary. I ended up here while I was on holiday in Greece. They told me about the problem of refugees in Athens, so I thought it was important to invest in this kind of experience.”

An integration model in the heart of the crisis

“We struggle together, we live together. Solidarity will win” is the motto the activists chose to highlight that the occupation of City Plaza is a true act of resistance against European migration policies. However, like every other squat in Athens, its days could be numbered. The Syriza government has decided to regain possession of some structures, so all occupied areas are now in danger.

The extensive media attention could be what saves the hotel, which is now being examined by some scholars as a best practice that is worth reproducing.

Still, unlike other squats, the City Plaza is a private property. Last winter its owner, former actress Aliki Papahela, declared to Time that she can no longer afford to pay the property taxes and would like to sell the building, but that the current occupation makes it impossible. At the same time, she recognised that the City Plaza project was necessary and important. In the end, the extensive media attention could be what saves the hotel, which is now being examined by some scholars as a best practice that is worth reproducing.

Valeria Raimondi has been living here for some months to write her urban studies PhD dissertation for the Gran Sasso Science Institute in L’Aquila. The core of her study is the accommodation of migrants and the forms of resistance they have to devise day after day. “The aim of City Plaza is to build a community starting from an organised housing project. We struggle together, we live together is a slogan that also encompasses the political sense of occupation,” the researcher underlines. “This is a positive and important experience, a best practice that should be exported for many reasons. First of all, because it’s a truly decent accommodation solution, as far as everyday life is concerned. Secondly, from the integration point of view, the City Plaza brings refugees into the urban context.”

“In Athens” Raimondi continues “all government-run camps are far from the city centre, some of them are even far from the city, without any connection, and migrants can’t go out freely. On the contrary, this hotel is near the Exharchia neighbourhood, a central position not only geographically but socially: this is the place where a real crisis economy has developed over the last number of years with self-organised facilities, self-managed soup kitchens, medicine collection points. A social basis has made this grassroots housing project easier than it would be in any other European city.” According to Raimondi, however, there are still some critical issues: “The collaboration model works, but only to a certain extent, since it is ensured by a rigid hierarchical organisation inside the hotel,” she adds. “Refugees have to be constantly spurred to participate; many of them contribute, but others just behave like guests.”

The project is entirely funded by private donations, which can be made on the official website. “Some people bring clothes and food every day,” Nasim explains at the reception desk, “others send money. We have supporters in many countries.” In fact, since the media began to speak about it, the City Plaza has become internationally famous. For its first birthday, activists organised a big party in Platia Protomagias, with traditional and ethnic music concerts and food from different countries. The squatters also created some gadgets with the brand of the refugee accommodation space: notebooks, shirts, and a small book that contains one year of stories and thoughts from those who managed to continue their journey. “It was one of the best experiences of my life,” writes Rabyee, who now lives in Dijon. “I live in France now, but I will try to come back home, and the City Plaza is my home.”

This article was first published on Open Migration. All photos in the article are by Alberta Aureli. Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis and proofreading by Alexander Booth.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)