How is a market constructed? How can we understand its multiple exchanges? In his book on the 1990s Russian transition to capitalism, one of the biggest moments of “market-construction”, Vadim Volkov shows how the hand of violent actors played a visible role in guaranteeing the enforcement of new property laws. He calls the protagonists “violent entrepreneurs”, organized individuals who were able to transform their violent resources – martial arts abilities, experience handling weapons, capacity to intimidate and so on – into economic capital. Instead of selling chairs, newspapers or iPhones, what these entrepreneurs sold was their ability to exercise coercion.

In the past few weeks the ‘mediation’ company Desokupa has returned to the Spanish media spotlight after their leading role in the eviction of La Yaya, a community center in Argüelles, a neighbourhood in Madrid. This is not a new situation. Since late 2016 several media have tried to understand the phenomenon of Desokupa: its director, Daniel Esteve, was interviewed by Spanish newspaper El Mundo and invited to Antena 3’s national television show, Espejo Público. Its employees, meanwhile, have been subject to several journalistic inquiries in which they have been defined as both violent (ex-boxers, ex-paramilitaries) and political actors (with strong ties to the far-right).

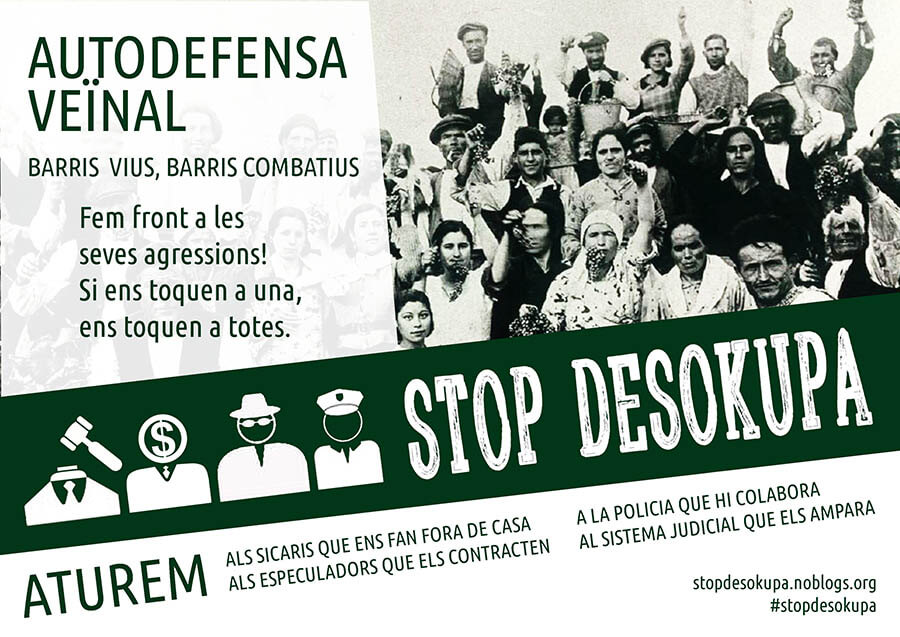

The most controversial side of the company, however, doesn’t concern the atypical profiles of its members, but rather, its activities: Desokupa executes eviction ‘mediations’ in Barcelona and Madrid, where they intervene in favour of the ‘okupied’ property’s owner. At best, the company develops its activities in a legal grey-zone, which in some cases may involve the use of extrajudicial violence. This has been denounced by both the Observatori DESC (through an ongoing complaint against Desokupa) and the neighbourhood organisation Stop Desokupa. The latter contends that, on top of being criminal, Esteve and his company’s activities are part of a mercenary avant-garde of new real estate speculation.

These criticisms of Desokupa quickly go beyond the narrow framework of the company’s actions, considering it instead as an actor in the larger power structures currently at play in Barcelona. Though Desokupa’s national expansion is already taking place, here we will try to understand the reasons for the appearance of the company in Barcelona’s particular context, how it relates to the real estate market and what the consequences are for the city.

Harnessing ‘potential’ violence

If we take a closer look at Desokupa’s activities (for example this video footage of their interventions and the testimonies of those involved), the company clearly fits into Volkov’s definition of violent entrepreneurs. It is important to recognise, however, that Daniel Esteve, Ernesto Navas, Jivko Ivanov and their partners do not go around beating people up, nor cashing extortions or shooting-out territorial rivals. There is an important gap between Desokupa and the 90s Russian mafia that we should not forget.

One of the characteristics of the Catalan company seems to be that, despite basing their economic activity on violent resources, these are not necessarily put into practice. Violence is held as a potential. This is probably their most entrepreneurial feature, through which we can best appreciate the ‘economization’ of violence carried out in their business. In his study of the Sicilian mafia, sociologist Diego Gambetta argues that the success of violent economic actors depends precisely on this rationalized use of violence: the less explicit it is, the more successful the exploitation of violent resources will be.

In economic terms, a beating is always followed by a series of risks (the physical effort, the possible death of the rival, troubles with the police, etc.), and every risk is a cost. But if the same results can be obtained through insinuation alone, one can get the same benefit at no cost. This is why the definition of Desokupa as violent entrepreneurs makes even more sense, as they do not exercise their violent potential. This is their key success.

It’s a success that seems to go hand in hand with a will to legitimate such violence socially: Esteve was once an underground MMA-fighter, then a promoter for the sport, and is now a Desokupa partner; Navas, after being sentenced for the attempted murder of an antifascist, was transformed into a regular worker and family man; the same is true of Ivanov, ex-paramilitary and now professionally settled.

This narrative points us to another important difference with the Sicilian and Russian mafias: Desokupa pretends to conduct its business within the law (a matter that we will consider later). These claims of legality and legitimacy are a key aspect of the company. Desokupa members are entrepreneurs in Volkov’s sense, as we have seen, but they also embody the everyday meaning of the word. This is something they attempt to portray, for instance, in their web page’s aesthetics, which is filled with references to dialogue, coherence and respect, over a background of the sun setting over Manhattan: a rhetoric in defence of private property and small property owners. We should not let the company’s violent features eclipse its most ‘businessy’ aspect: Desokupa is an actor in the real estate market, albeit quite a particular one. This is why the Stop Desokupa campaign has been denouncing the company’s activities for over a year, considering them a service for real estate speculation.

Which of the two versions should we accept? Is Desokupa a legal and legitimate company serving small property owners, or is it the armed wing of real estate? In order to try and answer these questions, we need to analyze Barcelona’s real estate market structure, and try to identify the role played by the company in the institutionalization of the city’s new touristic model.

The airbnbfication of Barcelona

The question of who employs Desokupa is central to understanding the conflicting positions about the company. According to Desokupa itself, their clients are exclusively small scale owners that have lost control of their property, as Esteve makes clear in all his public interventions. Yet even if this were the whole truth, we should not forget the context in which the company appears. This in fact is the main question: why does Desokupa exist?

From just a glance at the company’s etymology (Desokupa could be translated as De-squat), the answer is clear: because there are okupas (squatters). It’s similar to the way that without fascists there would not be antifascists. To avoid simplistic comparisons, we should consider the political component of many occupations, in line with anarchist movements and their critique of private property. Until now, though, nothing new.

Squats have always existed, we might say. So why has Desokupa been created now? Here it’s important to take into consideration the existence of ‘forced’ squats, those that are not politically voluntary. We could think here about the cases of people no longer able to pay for their mortgage or rent. Another case also exists, where property is squatted for its economic exploitation. Though such examples are a clear minority, they deserve to be mentioned for a fuller context. With all this in mind we can argue that if Desokupa has come into being today, it is because of an escalation in the number of squatting cases.

How do owners respond to this situation? In a report by En el Punto de Mira, a real estate businessman explains why he decided to hire Desokupa: he intended to refurbish one of his properties for later sale, but found it was squatted. Thanks to Desokupa’s intervention he was able to complete the project, cashing-in a 30% return on his investment. As described in the report, far from being anecdotal this case points to a trend in Barcelona’s real estate market where, in spite of the burst of the 2008 housing bubble, prices have not gone down. On the contrary, they keep on rising.

This produces an entire market around squatted dwellings, which, aside from having thrived after the real estate crisis (a second cause of squatting), offer a higher economic return. Why? Because owners of squatted properties, be they banks or individuals, are forced to lower their prices due to the marginal costs of non-exploitation during the time of the judicial procedure. Desokupa’s existence completes the equation: one can buy an under-priced flat because it is squatted, hire the company, which offers results within 48h, and for a ‘small’ sum (at least 4.000€) have it available for economic exploitation at market-level prices.

These prices are highly lucrative, as we can see if we follow the evolution of rents in Barcelona’s real estate market. Looking at 2016 data from online portal Idealista, we can observe how, between 2015 and 2016 alone prices in the city grew by 16.5 % (with a growth rate of 23.4 % in the province and 26.8 % in the whole of Catalonia). In some individual neighbourhoods (Sants, Sant-Andreu, Eixample) the variation surpasses 20%.

One of the main causes for the escalation of prices can be found in the proliferation of tourist-rental flats. If we take a glimpse at Airdna’s data or Kor Dwarshuis’s interactive representation, we can observe how the presence of this kind of rental has exploded over the last few years, going hand in hand with both the increase in prices and the number of evictions. We can interpret this phenomenon through Karl Polanyi. The economy and the markets, increasingly disembedded from social needs, rely on the destruction of inefficient or uneconomical social forms and institutions for their survival. In our case, the distribution of urban property, the level of land prices or the neighbourhood’s physiognomy need to be market-adjusted; a market where Airbnb and the like seem to pave the way.

Nevertheless, we should not consider the economy or the markets as abstract, ethereal entities. Behind every transaction is a buyer and a seller, a landlord and a tenant. Economic processes are concretised in real actors, because of the materiality of their consequences and the spaces in which they occur. Here we might think along the lines of geographer David Harvey, who has theorized about contemporaneous processes of capital territorialization in works such as Paris, Capital of Modernity or Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. One of the British geographer’s most cited concepts is that of ‘accumulation by dispossession’, a violent and necessary moment in the formation of capital in which, for a group to accumulate, it needs to ‘dispossess’ another of its goods. This notion parallels Marx’s definition of ‘primitive accumulation’, describing how the accumulation process requires institutional guaranties to be stabilized (the inclusion of private property rights in American law, for example, allowed for the ‘dispossession’ of the Native Americans’ land, its transfer to new owners and the subsequent economic exploitation).

The economy and the markets, increasingly disembedded from social needs, rely on the destruction of inefficient or uneconomical social forms and institutions for their survival.

Harvey’s innovation consists in considering dispossession not as a unique moment in the development of capitalism, but as a constant logic: to develop itself, capital needs to constantly find new spaces, which implies imprinting in them a double system (violent and institutional) that guarantees both dispossession and accumulation. In our case, we have seen how Desokupa is the guarantor of dispossession, enabling effective evictions that contribute to the development of Barcelona’s new touristic and urbanistic model. The institutional question still needs to be resolved though: where does the rule of law place itself here?

The city as a political conflict

As we have seen, Desokupa seems to fulfill an essential function in the establishment of the new real estate market in Barcelona. However, if we consider this from a panoramic point of view alone, we risk missing the concrete interest that the company represents for the owners of squatted dwellings. We have already touched upon some ideas regarding the financial returns of the so-called mediation that the company provides, but we must also note how these returns are the indirect result of the judicial treatment of such cases.

In this online presentation, only one of the characters speaks: “I am a squatter and I hold my rights!” they say. This is indeed true: as any citizen facing the law, the squatter has a series of rights. An occupant of a dwelling cannot be evicted without a judicial warrant if they have been living in it for more than 24 hours. According to estimates, the process between the owner’s complaint and the squatters’ eviction lasts an average of eight months. This is Desokupa’s raison d’etre: in Daniel Esteve’s own words, efficiency and speed versus the sluggishness of legal red tape.

To avoid criminal charges, the company has to present its activities as intermediation, i.e. as a deal between parts. This staging is best seen in the signing of contracts at the end of ‘successful’ operations, where the squatter accepts to leave the property, generally in exchange for a monetary sum. However, the characterization of the desokupas as intermediaries should not make us lose sight of their position in what is both an asymmetrical social relationship and a complex legal situation. Social asymmetry meaning that, as one sees their place of residence surrounded by heavy-set men with explicit knowledge of the use of force, any negotiation will be biased. And complex legal situation because in it, two incommensurable rights face each other. Both private property rights and housing rights are placed in the first article of the Spanish Constitution, with the difference that, while the former can only be alienated under “justified cause of public utility or social interest”, the latter alone “should be promoted by the authorities.”

In such cases what should prevail? Property or housing rights? The legal situation is further complicated when we consider that Desokupa could be incurring criminal activities in some of its interventions, as claimed by the Observatori DESC, who, in its formal complaint against Desokupa and some of its above-mentioned employees, accuses them of the crimes of coercion and trespassing, among others.

The city, seen as a social and political space, is a territory where rights are the result of political conflict, rather than statutory positions.

Beyond the case-by-case discussion of these evictions, we can thus identify not only the conflict between these two rights, but between two alternative interpretations of urban coexistence. Soon after the beginning of Desokupa’s media scandal, the aforementioned collective Stop Desokupa was created, aiming at the organisation of neighbours in denouncing the company’s business. We can interpret the actions conducted last summer by left-independentist youth organisation Arran against several tourist symbols in the same light. Using slogans such as “Tourism kills neighbourhoods”, they explicitly frame themselves in the same defense-matrix of a non-commercial organisation of housing, in opposition to Barcelona’s new touristic model.

At the exact opposite end of the spectrum we find Desokupa: whose position is based on the right to property, who line up with the actors in favor of a monetized urban geography, where inhabitants are selected through the filter of the market. This cooperation goes beyond discourse or particular cases. As documented by Diagonal, the company’s ties to big brokers of the real estate sector and security companies specialized in the “anti-squat” business make it an active actor in the production of the new city.

This tension regarding the form and organisation that the city ought to adopt is not necessarily negative. Conflict, David Harvey reminds us in a 2007 interview with El País, can even be considered as an ‘ideal’ to be pursued, without which our differences would remain unresolved. But there is no possibility of conflict resolution without institutional mediation.

What is being questioned is the role (passive until today) of justice and police regarding Desokupa’s activities, which de facto externalise eviction management with the use of intimidation and a lack of guarantees. Against what is essentially a challenge to the State’s monopoly of violence, they seem to have two options: to either respond with and within the law to the private exercise of violence, or to maintain their laissez-faire attitude. Until now the latter has been their preferred option, as can be seen in the informal collaboration between police forces and company members in several cases, the Argüelles example being only the most recent. The two ongoing complaints against Desokupa will force the justice system to take a side regarding the company. In the meantime, its activities continue.

In view of both the company’s expansion to the rest of Spain and the growing number of tourist rental apartments in Madrid, Seville and Valencia, and the consequent gentrification of neighbourhoods such as Lavapiés, Argüelles and Russafa, the debate about the compliance of cities with new real estate and touristic markets is far from over. This is especially pertinent in Barcelona, where the issue is at the heart of the public agenda following the election of Ada Colau, an anti-eviction activist, as major. Even if this has recently been overshadowed by the independence issue, both debates seem relatively autonomous, as the internationalization of touristic and financial flows will likely continue.

In this article we have seen the role that ‘violent entrepreneurs’ can play in the construction of new markets, but the question of to what extent neighbourhood and citizen associations can be a counterbalancing power remains an open one. The city, seen as a social and political space, is a territory where rights are the result of political conflict, rather than statutory positions. How much longer can we wait for an in-depth debate on the Spanish touristic model and its effect on cities?

* This piece was first published in Spanish on La Grieta. It was translated by the author.

** Lead image Aslak Raanes. Flickr/Some rights reserved

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)