Even before the referendum took place, one of the great risks of the UK changing its relationship with the EU was that it would downgrade European Citizenship and the free movement at the project’s core. The latest stage in the Brexit saga offers no reassurances, and indeed suggests that the citizenship rights of Europeans in general are being undermined. This should be a concern for all Europeans as a sign of what is to come, and a prompt to organize ourselves to fight against it.

The UK and European Commission came to an agreement in the early hours of Friday 8 December on the first stage of the negotiations over the UK’s withdrawal. Hailed as a ‘breakthrough’ by both UK newspapers and politicians who had been deliberately primed for the (unrealistic) prospect of there being ‘no-deal’ for months by shrewd UK and EU negotiating teams, the agreement also got wide political support across Europe, leading to the expectation that the European Council will judge there has been ‘sufficient progress’ in the negotiations about the UK leaving to move onto talking about the future relationship.

Two groups that are not celebrating the agreement are European citizens living in the UK, and UK citizens living in continental Europe. The 3 Million, one of the main campaigning groups representing approximately this number of Europeans in the UK, has said it is far from reassured by the deal. British in Europe, representing around 1.5 million UK citizens, has said the deal is a ‘double disaster’. This, despite the UK government and the European Commission claiming that the deal safeguards the rights of citizens, and these claims being widely and uncritically reported in mainstream media and press across the continent.

Let’s look more closely at the deal to see what people are upset about. As it stands the agreement only applies to the rights of citizens who have moved before the day the UK leaves the European Union. Amongst other things, it would require EU citizens in the UK to reapply to the Home Office for a permission to stay and allow for criminal record checks to be carried out, biometric information to be given, as well as a check on whether the EU citizens had been properly exercising freedom of movement rights when they came to the UK.

This might not sound like much, unless you are aware of the ways the UK Home office has systematically been failing to recognize the rights of EU citizens, for example sending out warning letters, ‘by mistake’, to legally resident EU citizens that they will be required to leave. Or that the UK has been seeking to define what counts as lawful exercise of free movement rights more and more restrictively, so as to require EU citizens to have comprehensive sickness insurance. Or that the UK has been detaining and deporting EU citizens on the grounds of their being homeless, or without work, or on the basis of minor offences like drinking alcohol in public. The agreement would also allow the UK to deport EU citizens before they have been able to appeal.

These provisions apply reciprocally, so that the same requirements as are imposed on EU citizens looking to stay in the UK, can be applied by EU member states on UK citizens seeking to say in the EU. This is the first of the ‘two disasters’ mentioned by British in Europe.

The second of the two disasters is that for the moment, there is no provision for UK citizens living in Europe to be able to keep their freedom of movement rights. Concretely, what this means is that the UK citizens living in Europe will not automatically have the right to residence, or to conduct business, or any of the other freedom of movement rights (non-discrimination, for example) outside of the member state where they are already resident. This issue has been deferred to later in the negotiations. Again, if you are not directly affected by this, it might not sound like much, but many UK citizens have built family lives in European countries, or work for businesses which have operations in multiple countries, and all of this is at risk.

All in all, after the agreement, many European families with members of different nationalities living in the UK and in the EU-27 are still wondering whether there is any place in Europe where they can all be together, a situation of continued uncertainty that many people have described as being ‘in-limbo’.

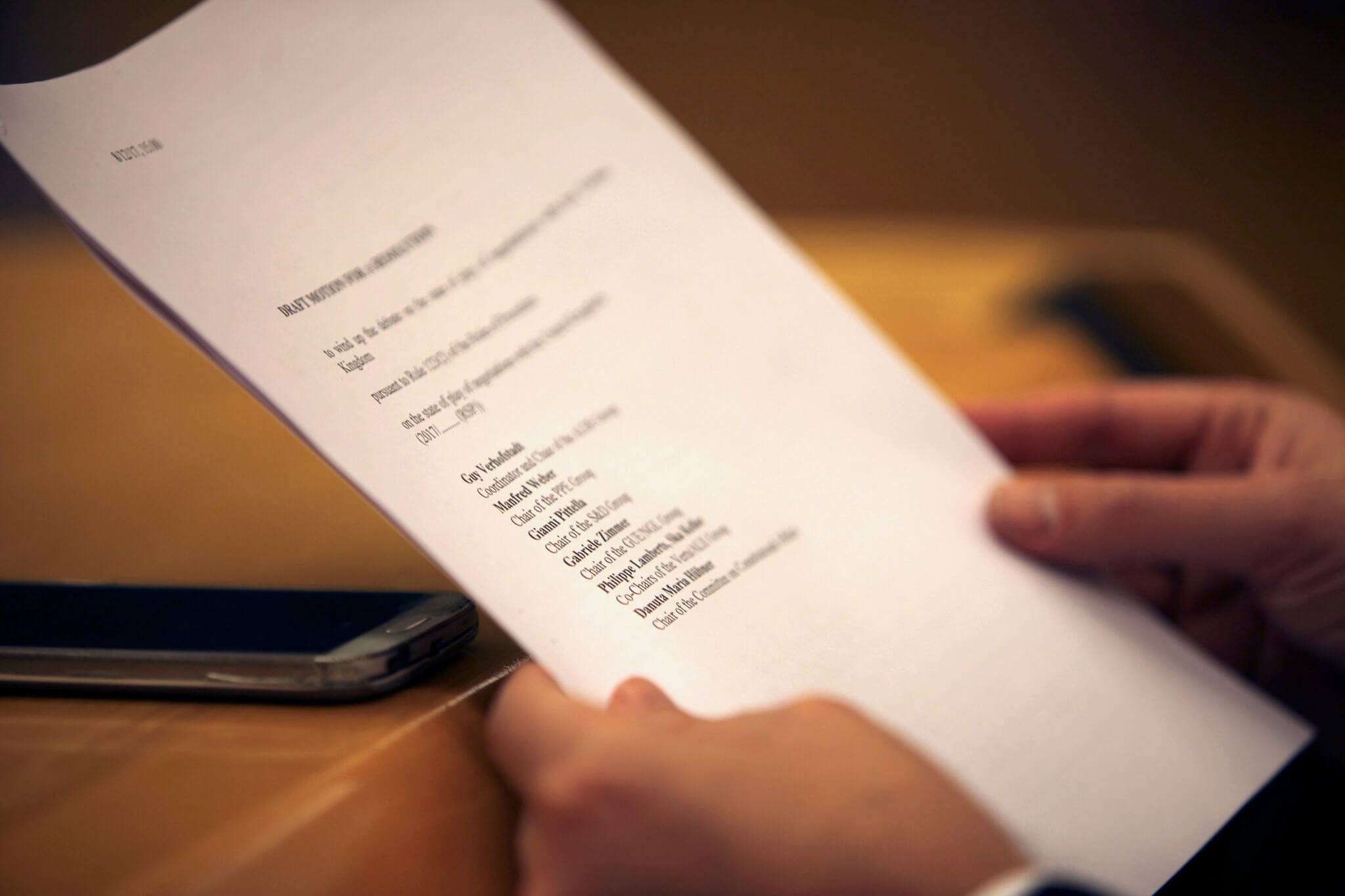

Maybe some of these issues will be resolved in further negotiations, as the lead Brexit spokesperson Guy Verhofstadt is insisting. But that all of them will be ironed out seems unlikely given the dynamics of the negotiations themselves. Stepping back from the details of what is agreed allows us to see this.

Back in May 2017, the European Commission appeared to propose to the UK to guarantee all existing acquired rights of citizens: UK citizens living in the EU would keep all their existing rights, including the rights of free movement, if EU citizens in the UK would keep all existing rights. The UK government turned this offer down, because the overriding interpretation given to the Brexit referendum vote by Theresa May and her team was that it was a vote against freedom of movement. Regrettably, that is also the dominant interpretation of the referendum given by the Labour Party in the UK as well, creating a wide consensus in UK politics that free movement is a problem.

Under pressure to show some progress in the negotiations, the European Commission caved-in, and allowed citizens rights to come into the negotiations: with the UK side’s main interest in this regard to try to limit the rights of EU citizens in the UK. From that point onwards there was always going to be some compromise of the rights of Europeans and British. Far from the British ‘caving in’ or simply agreeing to everything the European Union has required, the British attempt to close borders has had a major impact on the negotiations in this regard.

Through this concession and the start of using citizens as ‘bargaining chips’, the whole way of thinking about citizens rights has been re-nationalised. The consequence now is that citizens directly affected by the agreement, whether in the UK or EU, are all potentially required to seek a national decision to continue to enjoy their rights of residence, without much certainty that even if they are granted this right it will be respected in the future. After all, many of the EU citizens living in the UK had ‘indefinite right to remain’ physically stamped into the passports… What were European citizenship rights, have been transformed into national privileges, granted on application by nation-states and potentially removable in the future. This is a worrying sign for all Europeans. As Jane Golding, Chair of British in Europe, has said: it sends the message that if you move in Europe and rely on your European rights, you are at risk because they can be taken away from you.

the whole way of thinking about citizens rights has been re-nationalised

Taking a step even further back from the negotiations, we could also ask how legitimate it is for discussions to be only about the rights of those people who have already exercised free movement by the day the UK leaves the EU. European citizenship is understood in the treaties as additional to national citizenship, and therefore if the UK leaves the European Union it has seemed unavoidable to almost everyone that UK citizens will lose their European citizenship. And yet there is reason to question this. European citizenship has, for example, a charter of fundamental rights associated with it. Should people be able to vote to ‘opt-out’ of their fundamental rights? Should a majority be able to remove the ‘fundamental rights’ of a minority in a country through its vote? These questions are more difficult to answer than the quick conclusion that of course Brexit will lead to almost all UK citizens losing their European citizenship.

Peculiarly, it is through reflection on the status and situation of Ireland that these questions are starting to be asked again in the UK. As British media were reporting on the details and political reaction to the UK-Commission deal last Friday, all of a sudden newspapers and radio commentators seemed to realize that people born in Northern Ireland will be able to keep European citizenship once the UK leaves the UK, but people from the rest of the UK will not. This is because those people born in Northern Ireland can opt to have the citizenship of Republic of Ireland as well as their British citizenship, and therefore can keep European citizenship. This has nothing to do with the details of the agreement made between the Commission and the UK, and everything to do with the Good Friday agreement, but the sudden realisation of the consequences of this lead media commentators to suggest it seems rather unfair that someone born in Belfast can keep European Citizenship, and someone born in Brighton cannot. A more generous and progressive way of putting this point would be that it is unjust for anyone to lose their citizenship rights.

Many people opposed to Brexit in the United Kingdom and beyond are holding out for the contradictions created in Ireland by the impact of leaving the European Union, the single market and the customs union to bring the project crashing down. The agreement between the UK and the European Commission lays these contradictions down on paper. The UK wants simultaneously to avoid any hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and to be outside of the customs union and single market. The ‘fudge’ that has been used to cover this contradiction is called ‘regulatory alignment’, and is the idea that the UK can adopt laws which are aligned with (but not the same as…) EU laws, so that goods can flow freely over the border between the Republic and Northern Ireland. The only way this could work is if the UK follows the regulations decided on by the EU, without having a vote over what those are, a situation both Conservative and Labour politicians have described as unacceptable and equivalent to being a ‘vassal state’. Whether or not one appreciates the hyperbole, such an outcome seems to be rather the opposite of the message ‘take back control’ which was so successful in the referendum.

Realising the contradictions of this situation may lead UK politicians to reevaluate membership in the single market and customs union, having ruled out these options amongst other reasons because membership of the single market implies acceptance of free movement. The danger to European citizenship is that now concessions have been made to the UK on citizenship rights, any move of the UK back towards the single market and customs union will be premised on the idea that the deal for citizens does not get any better.

The Labour Party’s policy as recently outlined by its Brexit spokesperson Keir Starmer, for example, is that the UK should pay into the EU budget and have an association agreement with the EU which allows maximum access to the single market, but that free movement cannot be fully accepted. This sounds dangerously close to a situation where there is free movement for capital, but not for workers, and where there is acceptance of market rules, but without democratic say for UK taxpayers paying for them. Such a policy could only be supported either as a stop-gap for rejoining the European Union later on, or because one believes that the chances for democratic and progressive governance of the economy in the UK are so weak that the best chance to avoid de-regulation and lowering of workers rights is to tie these to the EU.

The dynamics of the debate are perhaps specific to the United Kingdom, but the affects on citizenship should be of concern to all Europeans. This is particularly the case with the moves towards a multi-speed Europe, which is also what many in the UK are bargaining on – a more flexible European Union in the future which can offer a more generous association agreement to the UK than is currently the case. In the scenario of making a multi-speed Europe, again and again the issue of the equality of rights for Europeans will come up: are the European rights of, say, a Hungarian the same as the European rights of a Spaniard, even if Hungary and Spain are not equally integrated into the European Union fast-lane? Unless citizens organize themselves across Europe to defend these rights now, starting with those affected by Brexit, they risk finding themselves divided and powerless later on.

*Lead image, British in Europe protest Theresa May in Florence. Credit: Jamie Mackay/All rights reserved

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)