Record-breaking temperatures have become something of a cliché. 2017, we are told, is set to round off a hat-trick of hottest years as global warming rates rise to their highest level since the interglacial Eemian period. But while Brits and Germans celebrated the June heatwave with BBQs – before the flash floods began that is – in parts of Southern Europe the mood has been far from festive. Pollution warnings, drought and water rationing have dominated headlines for weeks accompanied by images of burning forests, evacuated villages and furious protests beneath clouds of thick black smoke.

Wild fires are commonplace across the Mediterranean during the summer months, but the frequency and scale this year has been far beyond the norm. The blaze that broke out in Portugal in Pedrógão Grande in June, destroying 50,000 hectares and killing 62 people, was a particularly terrifying example but is far from isolated. This year the Adriatic has been hit particularly hard with uncontrolled fires still making their way across Southern Greece, Montenegro and, worst of all, Croatia, including areas that have previously avoided such phenomena.

Italy, where I’m writing this, has also struggled to contain the blazes. On average ten fires have been reported each day this month, from Piedmont to Puglia. In Sicily, where this is an annual struggle, the scale has proved overwhelming for under-resourced local response units. When a forest went into flame on the hills outside of Messina last week it quickly spread across the island killing livestock, destroying vast swathes of farmland. Around 1000 were evacuated from San Vito Lo Capo near Palermo with inhabitants and tourists forced to escape by water to avoid the dense smoke.

The destruction of the landscape itself is tragic to witness, not only for the damage caused to areas of outstanding natural beauty but for the loss of entire ecosystems. The black, scorched earth is certainly a powerful symbol of the much-debated anthropocene, but the thousands of animals and fauna that are dying each day, without a formal death toll, present specific problems for habitat analysis and conservation of non-human life.

It Isn’t Trump Ruining Our Planet, But Everyone Who Thinks We’ve Done Enough

Of course the immediate trigger for the fires varies from place to place. In the case of Portugal, for example, one of the likely factors was the mass planting of the highly flammable eucalyptus, used in the production of paper. In Sicily the fires are exacerbated by mass emigration and increasing abandoned farmland which results in a buildup of dry foliage. In France a stray cigarette butt is thought to have triggered the fires in Saint Cannat. Then there are institutional elements such as underfunding, cuts to park services and criminal arson. This is most evident in Naples where mafia groups regularly set fire to the forest around Vesuvius as a grotesque show of strength.

A recent study has predicted a 200% increase in such phenomena over the next 80 years.

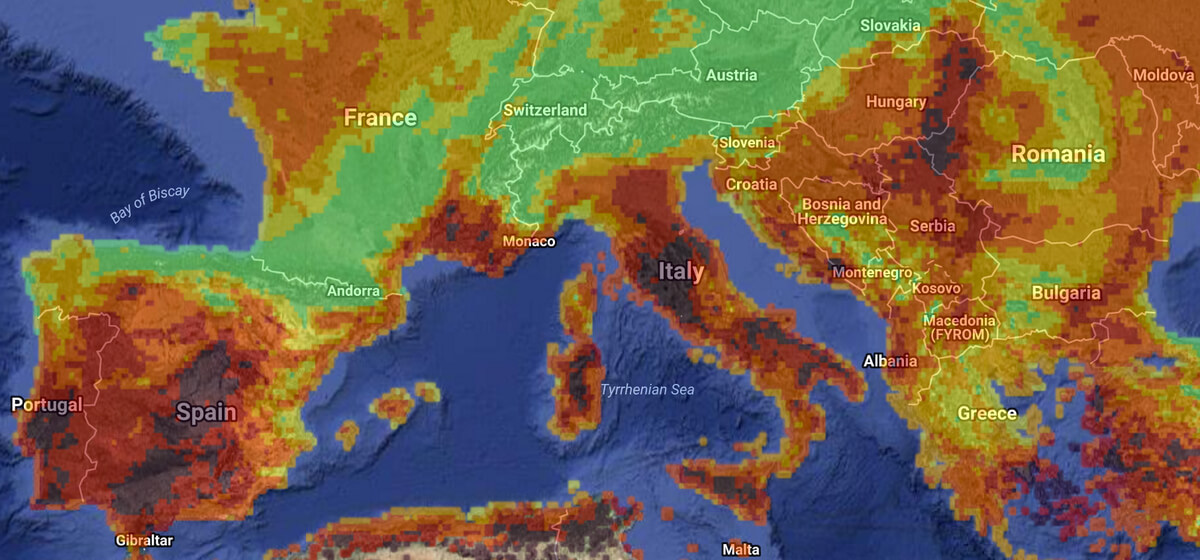

What unites these disparate examples, however, is the long-term decrease in rainfall across the region. The situation, in the words of Patrick Gonzalez, scientist at America’s National Park Service, is analogous to the US southwest. Rising temperatures and low precipitation are leading to the ‘rolling back’ of forests towards the north. The resulting dry land can lead to increased risk of wildfire during the summer months. As Adam Rogers put it in a well-researched article for WIRED magazine, “the Mediterranean climate is going to move northward and upward in elevation, turning more places into tinderboxes.” Figures vary but a recent study has predicted a 200% increase in such phenomena over the next 80 years under a high emissions scenario.

Right-wing populists have been strangely silent as one nation after another calls for international support but this hasn’t stopped their creative attempts to cast the blame on migrants. Meanwhile the EU is working hard across borders to limit the unfolding disaster with a dedicated body studying the phenomena (EFFIS), and various institutions and initiatives working to study and contain the damage. Their activity ranges from scientific analysis, prediction, policy proposals for prevention, satellite mapping, and, on the frontlines, an emergency response unit which provides a fleet of “water-bombing aircrafts and helicopters, fire-fighting equipment and personnel” to affected zones. Nonetheless, the European environment agency’s picture is a grim one.

“Climate change projections suggest substantial warming and increases in the number of droughts, heat waves and dry spells across most of the Mediterranean area and more generally in southern Europe. These projected changes would increase the length and severity of the fire season, the area at risk and the probability of large fires, possibly enhancing desertification.”

It is this last ‘possibly’ that will shape the future of the region in the long term. Tourism and food production are integral parts of the Mediterranean’s cultural and economic identity. If drought and fire increase at the predicted rates the quality produce and eventually the yield – of olive oil, grapes, vegetables, grain – will be brought to its knees in the next century. Taken alongside deindustrialization and the labour market crisis there is a real threat of further socio-economic catastrophe as a direct result of climate change not to mention implications for global food supply.

Last year in Sicily people were left without running water for weeks and forced to collect dew overnight on pieces of cling film spread on rooftops. What is rarely acknowledged is that many of the island’s emigrees – fleeing to work behind the counter at Pret, Starbucks and McDonalds in the Northern capitals – are in fact climate refugees within the EU itself, victims of the same processes that are bringing thousands of Bangladeshis to their own island’s shores. This is a highly localised example but one that speaks to a broader truth: that the problems of climate change, economic decline and people flow are more closely linked than is commonly recognised. One thing is for certain: in the face of such complexity, nation-states are powerless to act alone.

The homeless woman who froze to death: an environmental issue

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)