What “feminising politics” means has been largely written and discussed in Spain over the past couple of years. The debate, which is still developing, has some axes that can help us understand the difficulties of introducing feminism into politics without first transforming the political institutions and movements themselves from the inside through daily feminist actions in both public and domestic spaces. The level in which women involve and participate in political debates connects with their historical underrepresentation in the public spaces. But what is the scenario like in different parts of Europe? How are the debates around the concepts of ‘feminising’ or ‘feministing politics’ and the gender-transformative policies in countries like Spain and Romania? Oana Băluță and Carmen Castro Garcia bring some insights on the topic from two sides of Europe.

European Alternatives: What does feminising politics mean to you?

Oana Băluță: The notion covers both descriptive and substantive gender representation. Feminising descriptive representation means increasing women’s presence in decision making while feminising substantive representation strengthens the need to develop a gender inclusive political agenda that will advance women or gender friendly public policies. These approaches should be clearly understood as two ways of feminising politics that can work hand in hand or independently. There have been wide debates concerning the topic, I do not want to add more important nuances now, just to acknowledge their presence either in the academia or political praxis. In my opinion both dimensions are important. Women’s descriptive representation needs to increase in politics because women should make decisions that concern their own life and the life of their communities and countries. When women make political decisions they may also advance policies in some fields that concern especially women: gender based violence, work-life balance, sexual and reproductive rights etc. This does not mean that only women can support these types of policies or that only these fields are important for women. I believe there is no need for me to argue how important green policies, measures to fight poverty and to increase employment are for women. At the same time, I want to strengthen a fact grounded in the political experience of my country. When you analyse who have been the proponents of legislative changes in the field of gender violence, we notice that most of them have been women MPs and that advanced the most important changes. The theoretical nuances and the political praxis tells us that it is an ongoing debate that needs to be understood and situated in various country contexts to better reflect on the shape it takes.

When women make political decisions they may also advance policies in some fields that concern especially women: gender based violence, work-life balance, sexual and reproductive rights etc.

Feminising politics cannot be reduced only to formal politics, but also to activism and community mobilisation. Activists have their own ways and strategies to support representation and the development of an inclusive agenda. To resume, I correlate feminising politics to descriptive and substantive representation, to formal and institutional politics and activism.

Carmen Castro Garcia: In my opinion, the concept itself refers to the result of a higher presence and participation of women in politics. Obviously, when the participation ratio gets even and the representation is increasingly gender-equal, more elements will contribute to the political debate, and practical needs associated to gender roles (and not addressed in the androcentric culture of political organizations) will be brought up. However, thinking that said process will automatically mean a transformation of politics is more a projection of the ‘feminist desideratum’ than an immediate possibility.

European Alternatives: The concept (feminisation of politics) is often misunderstood as quotas for women in political representation rather than a symbolic and cultural transformation of the nature itself of political organising (with a focus, for example, on care work as basis of the production system, on welfare, on organising practices, on language…) What are the main directions that a feminisation of politics should take?

Oana Băluță: Quotas for women address descriptive representation. They are an answer to one problem: gender imbalance in politics or the descriptive masculinisation of politics. Quotas are not a miraculous instrument; they are not a panacea for each and every problem concerning women or gender or the world that we live in. If feminisation of politics means both the political inclusion of women and the inclusion of their interests/needs and perspectives, quotas per se address the first criteria.

It is reductionist to consider that quotas stand as the ultimate example for the feminisation of politics

It is reductionist to consider that quotas stand as the ultimate example for the feminisation of politics. It is an answer to one problem, and an important one if carefully implemented. Nevertheless, quotas are sometimes used as an instrument by political parties to tackle gender equality while ignoring other demands correlated to gender public policies. I will give you one example, a party may support descriptive representation, and it can embrace a conservative understanding of gender roles and identities. At the same time, it often happens that those opposing quotas focus more on the need to change gender policies, and almost not at all on the gender of representatives. A wide number of studies show the two are correlated in the sense that the gender of representatives does matter in regards to what policies are present on the agenda. We see again how challenging is the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation both on normative grounds, but also in the political life. In my opinion, both approaches that I briefly referred to fail to understand the role of quotas.

Feminisation of politics should address three layers: who makes decisions, policies that are shaped and the political praxis that should value more cooperation, participation and less the confrontational and competitive aspects of politics. The last layer is debatable since critics may argue that women may also be competitive and confrontational. Still, whether it is a feminisation of politics or not or just an outcome of more reasonability, decision makers need to also consider cooperation and solidarity as two landmarks of democracy.

Carmen Castro Garcia: Even though the issue of ‘feminizing’ politics seems to be activating a very interesting and necessary debate, I argue that for it to be more than a pose, it needs to come with real proposals to depatriarchalize the structure, politics, power, and society. To insist on the idea that by increasing the presence of women in the public sphere and assuming the ‘ethics of care’ in the functioning of structures we will gain the necessary potential to trigger a real change in them, is to engage on a discursive illusion.

European Alternatives: In what way does feminising politics mean a step towards more justice and inclusion of other oppressed subjects and collectives?

Oana Băluță: If feminising politics means more than descriptive representation and if the demands of activists become part of the formal political agenda, the answer is yes. Feminists have addressed diversity issues for a number of decades. Feminist ideas/ theoretical approaches and feminist community activism are dedicated to promoting social justice and inclusion not only of women, but also of other vulnerable persons. Think about feminists supporting green causes or fighting poverty or feminists that have been allies of the LGBTQ community. The unity principles of Women’s March from 2017 are a good example to understand that feminism is inclusive and nowadays it visibly and publicly addresses different subjects and collectives. These principles address: LGBTQIA+ rights, workers’ rights, disability rights, immigrant rights, environmental justice, etc. Show me another ideology or movement that is so inclusive and aware of other oppressed subjects and collectives…

Carmen Castro Garcia: Paritary democracy is necessary for the normalization of democracy, and for social justice. As parity increases, we widen the diversity in politics and rise the possibility of including those who are further from hegemonic masculinity, and have historically been excluded.

European Alternatives: “Feminising” can be a debatable term to define this change in priorities as it may be accused of implying an “essentialised” notion of female characteristics. What’s your take on this?

Oana Băluță: The concept of strategic essentialism was introduced in the 1980s by Gayatri Spivak. It is a political tactic that helps, for instance, minority groups, ethnic groups to mobilise on the basis of shared gendered, cultural or political identity. It is sometimes important from a strategic viewpoint to mobilise starting from some “essentialised” features to advance your interests and redesign the political agenda. This does not mean that those shared features define all aspects of the individuals. It is important to be aware of the fact that intersectionality, the term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, is again a very powerful and vivid concept that provoked universalism, racism and sexism. Coming back to the essentialised perception of female characteristics, when I argue that kindergartens and crèches need to be among policy priorities or that women must have access to reproductive rights, I do not believe that women are their bodies or that gender roles are static. Women and men have different gender roles in real lived life (we know about gender socialisation that teaches boys and girls about “their place”). If some roles generate inequality, I think it is our responsibility to advance those policies that will either reduce or eliminate inequality. These policies also reflect a change in priorities towards a “feminised agenda”. If I argue for access to safe abortion, this does not mean that giving birth is women’s duty. It is a choice and when materialised, I consider it a political responsibility to make sure women have access to safe public maternities. Romania has the highest morality rate in Europe due to cervical cancer. Policies to address the incredibly high mortality rate due to breast cancer or cervical cancer ought to be a priority. Does this mean feminising healthcare policies? It might, but the honest truth is I do not care. I only care for the development of a responsive health strategy that also includes the problems, needs and interests of women.

Carmen Castro Garcia: I don’t think the debate should be focused in the idea of ‘feminization of politics’ because, despite the good intentions, there is a high risk of it being used as an ploy to distract, to reinforce the stereotypically gendered system through the symbolic value of labeling certain skills –desirable in politics– as ‘feminine”.

We need to directly address the specific inequalities that take place within the political structure, the subtle and not-so-subtle violence mechanisms that are always present, or the playing down of feminists in politics. There has to be zero tolerance to mansplaining in left-wing organizations, to the resistance to direct the public budget to gender equality, and an eradication of femicide, with the active implication of the whole political structure. These are just some aspects of the whole process of de-patriarchalization.

European Alternatives: The Feminisation of politics is definitely a tenet of the change that many “rebel cities” are bringing forward throughout Europe, especially in Spain. In what way the “new municipalities” or local politics are translating or should translate the concept of feminisation of politics into practice?

Carmen Castro Garcia: I firmly believe that it is necessary to insist in a change of the symbolic imaginary. Leaderships like Ada Colau’s (Barcelona), Manuela Carmena (Madrid), or Mónica Oltra (País Valencià) encourage another way of making politics, closer to everyday life concerns, explicitly dealing with social care; it has to do with the advocacy of public services, such as aid for dependent people, nursery school, nursing homes, and the prevention of male violence. It is obvious that these leaderships encourage a willingness towards these issues, but they do not guarantee that the patriarchal and heteronormative structures will start questioning male privilege, developing feminist politics, or creating a real change in the order of their priorities.

***

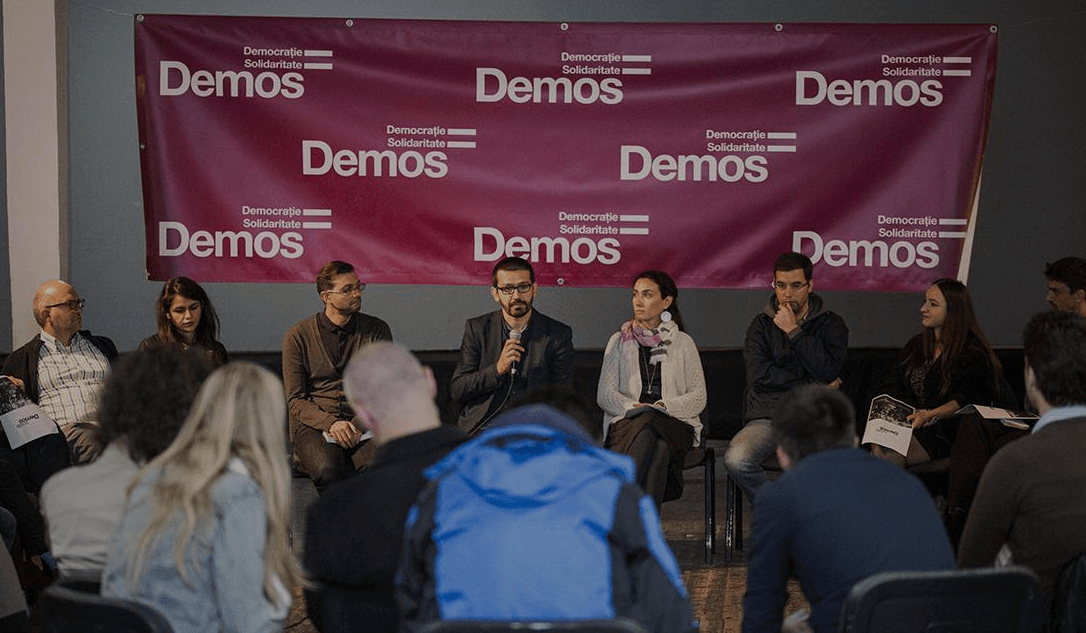

Oana Băluță is an Associate Professor on the Faculty of Journalism and Communication Studies at the University of Bucharest and member of the new Initiative Group Demos in Romania.

Carmen Castro Garcia holds a PhD in Economics, specialised in Policies and in birth permit systems. She reflect about it in her last book “Políticas de igualdad. Permisos por nacimiento y transformación de los roles de género”. You can follow her on Twitter @sinGENEROdDUDAS and on her website http://singenerodedudas.com

This article was first published in the journal of TRANSEUROPA Festival.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)