Faced with a bleak political landscape, Italian activists involved with a social centre in a former psychiatric hospital in Naples (Ex-Opg Je’ So Pazzo) have decided to launch an electoral platform with ambitions beyond the 4 March. Dubbed Potere al Popolo (Power to the People), it explicitly opposes not just the xenophobic right but the managerialism and obsession with the ‘centre ground’ that has dominated social democratic parties in Europe.

The platform launched in November at an assembly in Rome, with local groups springing up around the country to discuss political issues and policy priorities as well as the practicalities of candidates, electoral strategy and campaigning. One of the defining features of Potere al Popolo is its desire to speak to young, disenfranchised, precarious workers. This is borne naturally from the fact that many of its activists are made up of these demographic categories, although the platform also incorporates elements of the ‘old’ left such as Rifondazione Comunista.

This overwhelmingly young and vibrant platform contrasts with the other electoral offers, dominated not only by the 81 year-old Berlusconi and the so-called ‘coalition of the right’, but with the stale, male, pale Liberi e Uguali, led by 73 year-old President of the Senate, Pietro Grasso. The problem with Liberi e Uguali, according to Potere al Popolo activists, is not just their lack of conviction in truly emancipatory politics but their lack of participatory, bottom-up democracy. Potere al Popolo call for decision-making by the people, not just a few behind closed doors.

This generational chasm between the social democrats and radical left starkly reflects the demographics of Italy, with polls suggesting 70% of young people will abstain. After years of stagnation and growing youth unemployment (currently 35%), young people have been left to pursue careers elsewhere. This effect of EU free movement of labour, incorporating disparate economies, has provided opportunities for younger Europeans to live and work abroad; but also for ageing politicians to ignore the huge demographic and economic crises, epitomised by the governing Democratic Party’s (PD) Minister for Labour Giuliano Poletti claiming last December that it was good that young people were emigrating, because it meant they weren’t getting in the way.

Beyond the ‘least bad’ option

Given the political programme of Potere al Popolo, it is logical, if slightly unusual, that they have focused attention on Italians living abroad. After attending the first London assembly I spoke with some of those present, as well as Giuliano from Naples, one of the key organisers in Italy. One of the striking things from those that I spoke to was that, in the years they have been living here, all have felt shut out from Italian politics almost completely, and not just because of geographical distance. One UK-based activist described how, since the Eurozone crisis, “the horizon of choice and agency in the Italian political spectrum has been shrinking day by day.” As Giuliano put it, “we couldn’t sit back and watch the drift to the right.”

Political issues were debated and discussed, followed by a practical session aimed at ensuring that they could gather as many signatures as possible to stand in the elections. Italian parties need to get 25,000 signatures, and for those wanting to stand for the 5 Chamber of Deputies and 2 Senate seats designated for Italians living elsewhere in Europe, 500 signatures of Italians living in Europe need to be gathered at consulates. The signatories must be registered on a formal list of those as living abroad, so a great deal of bureaucratic heavy-lifting must be done before Potere al Popolo can even put forward candidates. This new law, applicable only to new parties without parliamentarians, is designed specifically to stop new political forces emerging.

A number of the assembly participants were Labour Party members and involved in either Labour or Momentum, and the meeting was addressed in fluent Italian by Laura Parker, Momentum’s National Co-ordinator. Parker gave an overview of Momentum, the two leadership campaigns, and last year’s general election, as well as emphasising the key aspects of its mobilising strategy in social media and technological innovation. Crucially, she spoke of the contradictions in Momentum as a social movement that actually started from a victorious leadership campaign of a major political party, and which has yet to find its feet as a real “grassroots” movement. On this point she stated that Momentum could learn a great deal from Potere al Popolo and Je’ So Pazzo in particular on building social and community infrastructure.

Despite the obvious influence from Corbyn’s Labour and Momentum, the differences between the UK and Italian left are stark. A Corbyn-style assault on the PD is unthinkable, and the activists I spoke to were sure that the party must implode before the left can really start making progress. One activist pointed to the Portuguese Bloco de Esquerda (Left Bloc) as more comparable to the Italian example, whose slow ascent from the margins to the mainstream serves as a more realistic prospect. The perspective taken by the Je So’ Pazzo activists is of a long-term project, with 4 March as the starting rather than end point.

One lesson Potere al Popolo has learnt from the mistakes of the Italian left in the last 20 years is not to fall into the trap of choosing the “least worst” option, which is what those advocating a PD vote argue (Renzi desperately describes a vote for centre-left rivals Liberi e Uguali as a gift to the far-right). To do so would be to continue the failed stunted horizons of the Berlusconi years that “has brought us to the disaster in which we find ourselves”, says Giuliano. Instead, only a “real alternative” can block the advance of the right. While the Five Star Movement style themselves as populists and anti-establishment, the London-based Potere al Popolo activists see them as a “false opposition” to the corrupt mainstream parties.

Regaining ties

Given that their aim is not short-term but about initiating a longer process, there are no high expectations for the coming elections. But with 150 assemblies and 20,000 participants mobilised since the middle of November, the ground has been laid for a serious left-wing challenge to emerge against what is looking to be either a coalition of the right or no overall control followed by a technocratic government.

Signalling its ambitions beyond electioneering, Potere al Popolo sees itself more as a national co-ordination of the various struggles and divergent political rhythms of social movements across the country: all the candidates come from social movements and workers’ struggles. In a striking election broadcast, Potere al Popolo present their spokesperson, 37 year old Viola Carofalo, a precariously-employed researcher from the Je’ So Pazzo collective in Naples. Subverting the legal obligation to nominate a capo politico (political leader), the video shows a string of people stating “I am the capo politico”, ending with Viola stating “I’m not the capo politico, I’m just a spokesperson, and I couldn’t be anything else because our movement is a collective one… over 100 assemblies, a manifesto written together.”

To take the London assembly as an example, such a mode of organising emphasises the importance of politics that isn’t focused solely on chasing the Chamber and Senate seats (in Europe this can’t be achieved as the threshold of signatories required to stand candidates was not met). Instead, Potere al Popolo’s focus on external assemblies – London, Brussels, Barcelona, Madrid, Berlin, Paris, Marseille, Bristol, Moscow, Lausanne, Bern, Dublin, Zurich – is reflective of their broader participatory politics. In a country like Italy where political discourse seems obsessed with the migrant “emergency”, even framing it as an “invasion”, Potere al Popolo focus instead on the problem of emigration. This mirrors the debate over Brexit and immigration in Northern Europe, where the obsession over the impact of migrants dominates in their host country, ignoring the countries of origin and the reason for migration.

In Italy, emigration figures are three times that of pre-crisis years, with around 5.4 million Italians now living outside of Italy: 10% of the population. 1.5 million of this number emigrated after 2008. According to Giuliano, Potere al Popolo considers each one of these a “punch in the stomach”, emphasising the social, communal and familial impact. Refusing to abandon emigrants to their fate, Potere al Popolo see it as a small tragedy that Italians are known as the “waiters of Europe”, constrained by lack of opportunities in their home country to move and take on menial jobs elsewhere, despite education and qualifications.

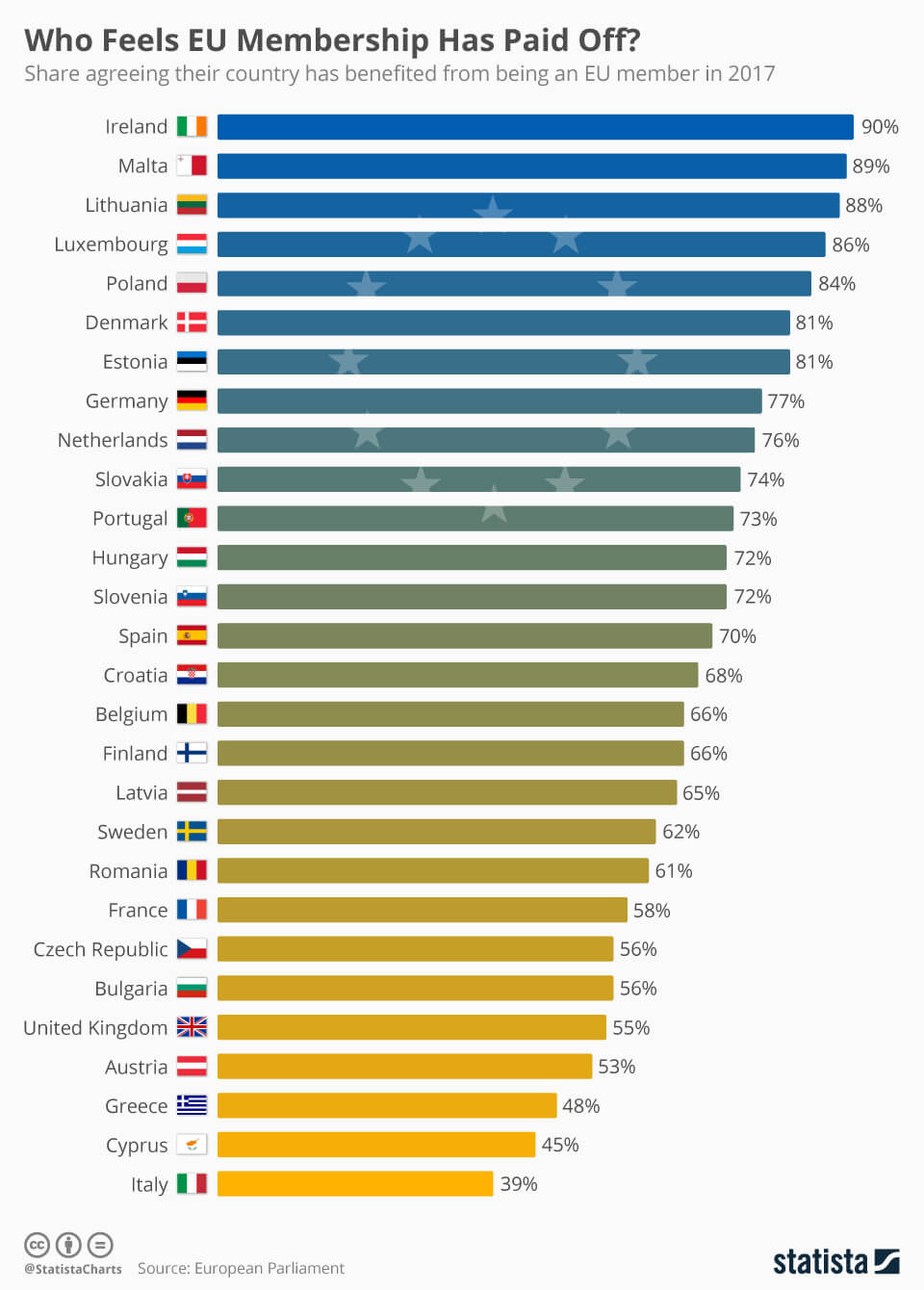

Whilst Liberi e Uguali propound the advantages of the European Union, and Renzi’s PD this month called for a “United States of Europe”, Potere al Popolo’s coalition includes the Eurosceptic Eurostop group and has been vocal against the EU fiscal compact that keeps Italy locked in austerity and against the EU’s vision of emigration as a solution to youth unemployment. Given the unpopularity of Brussels in the country (see above) there is potentially ground here for success.

“Our generation is dispersed,” one activist told me, “not just politically but also geographically, and this limits our agency, the collective power that we can exert.” By holding these assemblies across Europe, their hope is to start rebuilding communities. “It is a way of regaining by hand the ties broken by neoliberal policies. It is a way to construct communities that are not based only on geographical origin – Italy – but on elements of the present and future: you are together because you share a common purpose, those that emigrate and of the difficulties and joy it entails; you are together because you struggle, side by side, to improve your own conditions.”

* Lead image, Potere al Popolo assembly, Rome. Credit: PaP, Some rights reserved.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)