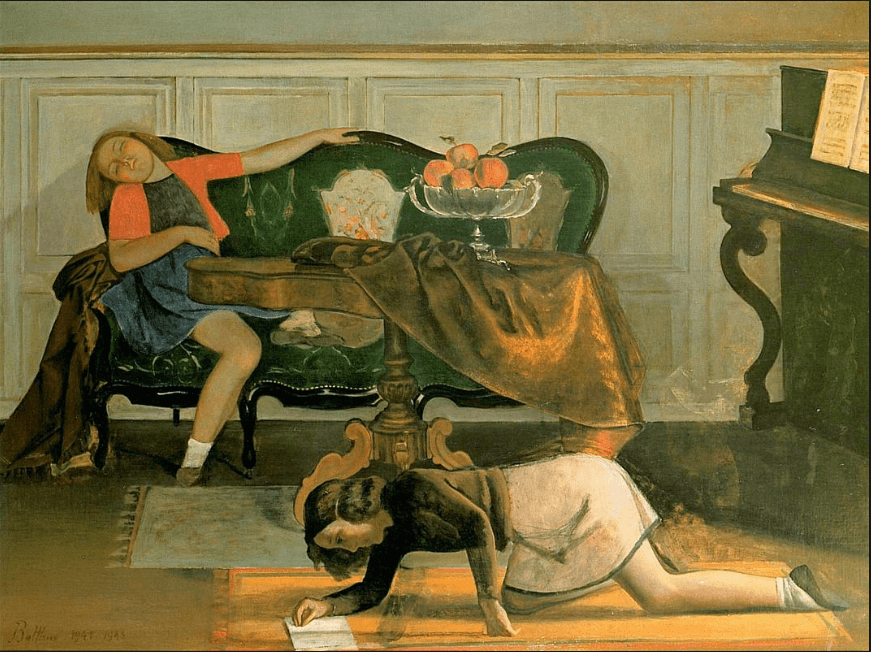

I recently went to an exhibition that has given people in Spain plenty to talk about over the past few months: Derain, Balthus, Giacometti. A friendship between artists. I admit that I went out of pure curiosity: to corroborate or deny the disturbing character that public opinion presupposes of Balthus’s girls. Indeed the exhibition contains some of his most controversial work, that which has female adolescents as its protagonists: The Happy days, made by the artist between 1944 and 1946, in addition to The bedroom (1947-48) and The Hubert children and Thérèse Blanchard (1937).

In these works, Balthus blurs the limits that were drawn in the Enlightenment between art and pornography. If only for that historical question, these deserve to be contemplated. Aesthetic judgment – Kant pointed out in the eighteenth century – is that which is produced from a “disinterested complacency.” Beauty, therefore, must never be convulsed; contemplation must be exercised from a position of calm. And yet, on the contrary, Balthus’s imagination disturbs us.

Far from reaffirming the hackneyed Balthusian figure of the ‘Lolita’, the curator of this exhibition, Jacqueline Munck, has given a more nuanced analysis of paintings such as Happy days, Sleeping girl (1943) and Reclining nude (1983- 86), which share a room with three other paintings by Derain and a sculpture by Giacometti. According to Munck, these artworks have a thematic vocation: the representation of the lying woman. The visitor is almost at the end of the course of the exhibition when they are faced with a kind of improvised bedroom, with seven artworks representing women lying on a couch or bed posing for artists as if in a seductive dream. The room’s explanatory panel rightly emphasizes that this is a topic that can be considered classic. Indeed, the history of art is crammed with horizontal women; some theorists, such as Lynda Nead or Mª Ángeles Fernández López, go so far as to imply that the history of Western art is no different from that of the representation of the female body. [1] To understand the disturbing bias in the Balthusian Lolitas, however, we must look at the far from innocent genealogy of that topic.

Venus Reclining

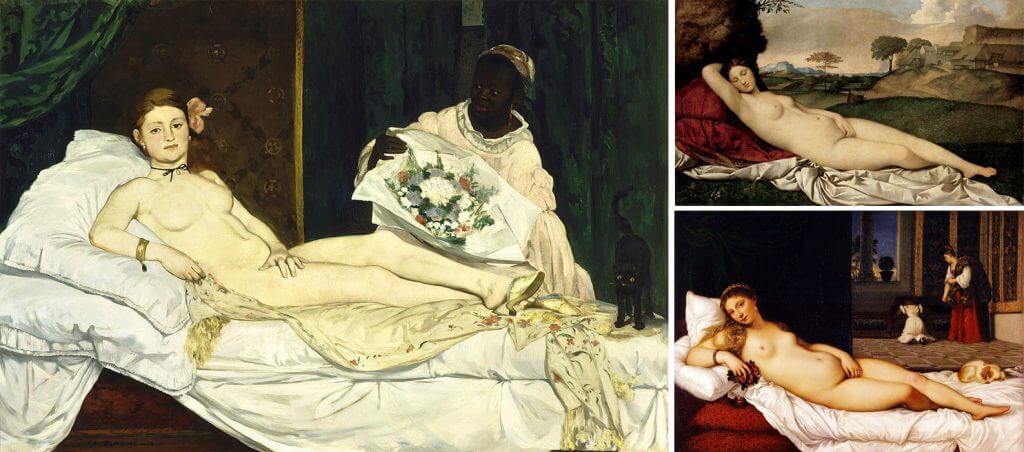

The representation of the reclining woman was already kidnapped under the sign of the erotic at its very birth, through the pictorial tradition of the reclining Venus. This was present initially in classical aesthetics, as is shown, for example, in the fresco of Aphrodite in Pompeii, and was popularized with Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (1507-1510), an artwork that the author left unfinished. The painting was probably finished by Titian in 1511. It’s not surprising therefore that Giorgione’s artwork influenced the composition of the Venus of Urbino by Titian himself (1534), and that this was the inspiration of the much later Olympia by Manet (1863).

In Manet’s work, the image of Venus becomes worldly; showing, without dissimulation, that the goddess of love is a woman no different from the prostitute. With this, the French painter, while profaning the image of the goddess, endowed prostitution with a metaphysical halo by aestheticizing its activity, a task that Baudelaire also initiated in those same years in literature with The Flowers of Evil, published in 1857. Together with Flaubert, Baudelaire was put on trial, accused not only of showing but also extolling the immoralities of Parisian society. We can see a vast collection of “horizontal women” who, from their insinuating beds, go through the history of art from the Renaissance and the Baroque – Venus from the mirror by Velázquez (c.1648) or La maja desnuda from Goya (1790-1800) – to the contemporary world – Recumbent Nude by Courbet (1862), Recumbent Nude by Modigliani (1917-18) or Nude on the red sofa by Lucian Freud (1889-1891) ) – to give just a few examples.

The myth of Danaë

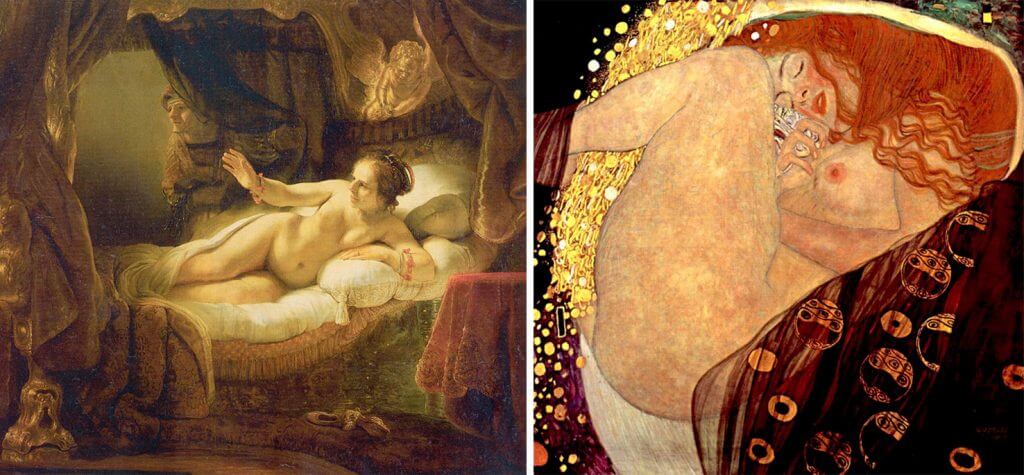

In parallel to the theme of the Venuses, we need to analysis the specific figure of the reclining woman. I refer to the heritage, mainly through Titian, Tintoretto or Rembrandt, of the Greek myth of Danaë. Ovid briefly narrates this story in his Metamorphosis, which begins when the oracle confesses to Acrisio, father of Danaë, that he would die at the hands of the one who was his grandson. [2] To prevent the goddess from exercising a promiscuous sexuality, they locked her in a cell. However, Zeus managed to enter through the cracks in the wall, in the form of golden rain, and impregnated Danaë. Titian painted several canvases about this myth. The first version alluded to the love of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese with a courtesan. In Danaë receiving the rain of gold (1560-1565), he shows us an ecstatic woman, who, laying down and expectant, awaits the desired and appetizing encounter with the god. [2]

The contemporaneity of the Danaë myth goes through a progressive loss of autonomy of the protagonist, who acquires an erotic lethargy over the centuries.

The gestures in the representation of this goddess will vary substantially centuries later with Gustav Klimt’s Danaë (1907). The contemporaneity of the Danaë myth goes through a progressive loss of autonomy of the protagonist, who acquires an erotic lethargy over the centuries. In the Baroque period, Danaë was still an active subject: although she was lying on the bed, she was awake and even reclined on the bed in a restless attitude – as in the artworks of Tintoretto (1570) or Rembrandt (1636). After Danaë’s proactive attitude, it was not only the idea of consent but also the desired sexual encounter: the erotic of the artwork was present in the liveliness of the protagonist. Danae wanted to have relations with Zeus and she looked forward to the rain.

On the contrary, in the Klimt version we observe several different nuances. We could interpret that Danaë is sleeping peacefully and, happy in her ignorant dream, is penetrated by the god. In this case, the Zeus of Klimt’s Danaë would no longer be an intrepid lover who, with determination, avoids Acrisio’s impediments in order to meet his beloved; instead Zeus would now be a rapist who is seduced by feminine helplessness. Therefore, Klimt’s artwork would not show an ingenious erotic encounter, as in the baroque cases, but a relationship of doubly perverse submission, because there is a relationship of domination and, in addition, a voyeuristic component; because although the spectators are participants in the act, the protagonist ignores it.

Yet this is not the only possible analysis of Klimt’s painting. Alfonso Troisi makes a more generous reading and considers that the face of Danaë does not reflect an ignorant dream but, in fact, the exact moment following amorous ecstasy. [4] There are two features of the artwork that, on the contrary, would support a more crude reading of Klimt’s painting in front of Troisi’s thesis: the fetal position of the protagonist, which emphasizes her state of absolute helplessness and abandonment; and the perspective with which Klimt composes the canvas, placing the viewers of Danaë in a vertical vision that dominates the scene.

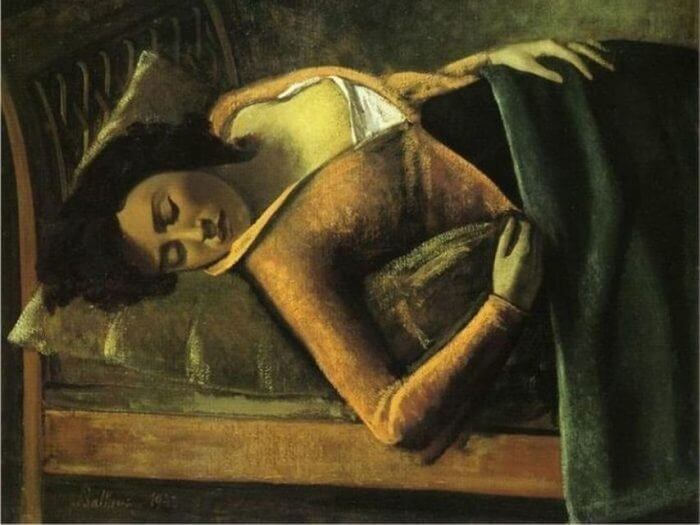

This is a perspective we also find in a beautiful artwork by Balthus in the exhibition, in Sleeping Girl (1943), in which a standing spectator contemplates the horizontal woman. Both Klimt and Balthus are masters in masking the relations of subjection through aestheticisation, endowing with a sacred halo. Rather than through the representation of the subject itself, this is executed in their production through apparently irrelevant symbols – the way of composing the position of the naked legs of women – and the perspective adopted by the work, which places us above the protagonists, exercising dominion through the gaze.

This power of gaze over the sleeping woman also points out an erotic ambiguity that is picked up by Jacqueline Munck, alluding to the influence of Carpaccio’s The Dream of Saint Ursula (1495) – a canvas in which an angel appears in dreams forewarning the death of the saint – on Balthus’s The Dream II (1956-57). This is the dichotomy between Eros and Thanatos, between “desire and destruction” that occurs in the representation of the theme of the night visit, which usually refers to the arrival of a love that, from this elevated and stealthy position, protects but also spies on horizontal women, because they never know if it is a guardian or a threat. [5]

Glacial women

The tradition of the eroticization of the female dream begins in the already mentioned Sleeping Venus by Giorgione, and reaches the “raped” Danaë by Klimt and the obscene helplessness of the Balthusian Lolitas. In literature it will be consolidated in the brutal myth of the sleeping beauty, which, entitled Talía, Sun and Moon, initially appeared in a collection of stories entitled Pentamerone by Giambattista Basile in 1635, and which is far from the Disney story.

In fact the idea of a sexual act that is capable of vivifying a sleeping or fainted person, cadaverous or inorganic, had already appeared in the classic myth of Pygmalion, which anticipates contemporary sexual fantasies concerning automatons. Again we have to refer to Metamorphosis. In Book X, Ovid presents the story of a clumsy bachelor evicted from all expectations of love: Pygmalion. Faced with a sexual and affective wasteland Pygmalion conceives an ingenious and beautiful paraphilic solution to his solitude: he builds his own sculpture of the woman of his dreams; yes, that woman that so easily surpasses the disappointment, defects and shadows of a human being. Pygmalion, attentive, generous and gallant, gives jewelry, flowers and kisses to his statue, until one day he asks the gods for that “ivory virgin” as a wife. Finally “once the ivory is touched it softens and deposes its rigor in him, and his fingers settle and he gives way.” [6]

The Pygmalion myth inaugurates a sexual imaginary in which the indifference or distance of the beloved woman – cold as a statue – begins to be interpreted as hope of voluptuousness, as an invitation to the sexual act. This is an idea that will be strongly reaffirmed in the Victorian imagination of the 19th century through the figure of the ‘angel in the house’, which referred to the passive, glacial and weakened women who exalted a “suppressed sexuality, proper of the asexual and virginal saint”. [7]

This aestheticization of the ideal of the glacial woman, insensitive and impassive, served to disguise, in the erotic, a great terror of the time: the incapacity that bourgeois men were experiencing in sexually satisfying women and the lack of male desire.

The word “frigidity” appeared in medical vocabulary between 1840 and 1850 and was a constant of the Victorian era, a time that distrusted sex in general. Jules Michelet, a prominent French historian of the nineteenth century who published, with great success, some of the patriarchal handbooks of his time, such as La femme (1859) and L’amour (1858), was an example of the contradictory Victorian obsessions that will reach the artwork of Balthus. Michelet argued strongly that the greatest enemy of the French Republic had been the struggle of women for emancipation – the internationalization of the feminist movement occurred in the mid-nineteenth century with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 – and that these were essentially, menstruating and sick beings whose only vital vocation was to love and serve their husband. Such statements served only to hide the complex blushes that men were experiencing at the time. Michelet was quite clumsy when it came to sex, and, as Kniebhler tells us, “it is known that he never managed to make Athenäis vibrate, who was content with being an object of desire, eating well, sleeping well: that was all her sensuality”. [8]

As Kniebhler continues, by the mid-nineteenth century exciting a woman had become a problematic enigma. Between 1848 and 1888 Dr. Auguste Debay, a French military doctor, published a curious book which was reissued more than a hundred times in which he detailed the ways in which a woman could be stimulated: it was titled Hygiene and philosophy of marriage. Likewise, Laqueur says that the vocabulary referring to the clitoris was condemned to ostracism in the 19th century and did not reappear until 1905 with Freud, in whom it will be considered not a source of feminine pleasure but a somatic space of sexual deviance. [9] Interestingly, the prevailing frigidity in the Victorian era ended up becoming a sexual myth through the vampire portraits of Jewish aristocratic women by Gustav Klimt within Viennese secessionism. This aestheticization of the ideal of the glacial woman, insensitive and impassive, served to disguise, in the erotic, a great terror of the time: the incapacity that bourgeois men were experiencing in sexually satisfying women and the lack of male desire. The undaunted, languid and absent was transformed at the end of the 19th century into an erotic element, hence it was a submerged sensuality or “latent eroticism” – as Munck calls it [10] – that hid itself in the representation of the sleeping woman and that also we find in the Balthus’ portraits of indifferent laid-out pubescents.

Mary Cassatt, a precursor to Balthus

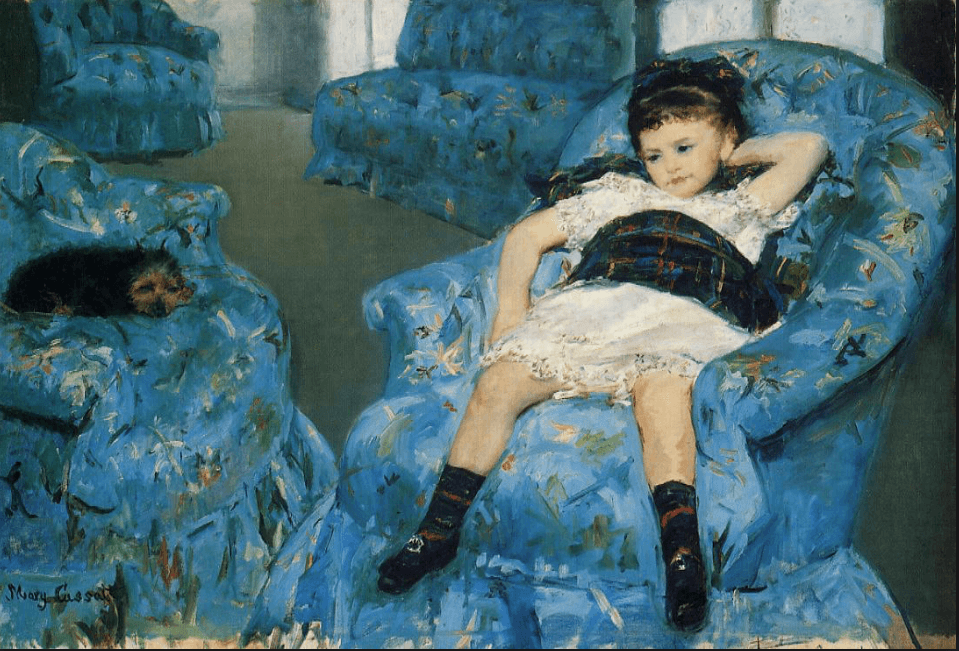

The representation of sexualised puberty was a reaction to the taboos of Victorian society and did not begin in the mid-twentieth century with Balthus, but at at the end of the previous century. Interestingly, it is a woman that stands out here, the American painter Mary Cassatt, and in particular her enigmatic 1878 painting, Young girl in a blue armchair.

This painting brings in two watershed ideas. In the first place, Cassatt openly exhibits the legs of a girl, who, moreover, does not feel constricted on the sofa; on the contrary, her position shows laziness, comfort, indifference towards the spectators. Yet unlike the half-hearted pubescents of Balthus, her carelessness is not characteristic of any imposture, whose indolence is the effect of an erotic pose that the author wishes to imprint on them. In Balthus’s work, women have a studied carelessness in the position of their legs, which, compared to Mary Cassatt’s painting, is artificial, the result of a millimeter change in composition.

Covering legs was a characteristic Victorian trope, a time when “the thighs, the legs, become indecent in all their extension. Victorian prudishness comes to dress the legs of the tables” [11]. The exaltation of naked legs, which is also contemplated in the can-can of the Belle Époque, was a reaction against conservatism. However, this carefree and liberated view of puberty does not take place in Mary Cassatt from a position of power. As Griselda Pollock points out, Cassatt achieves it through the perspective that she prints on the scene [12]. It is not an adult who is observing the image, but someone who stands at the height of the infant, showing us the world from the position of the child. With this, Cassatt emancipates the infantile imaginary, while Balthus simply puts it at the service of the adult world’s desires, as in the controversial artwork Thérèse dreaming.

The privilege of being Balthus

As we can see, the imaginary of the reclining woman has not been limited to representing a resting woman: it has been an erotic invitation, a reflection of the artist’s desire. And there are desires, like those that Balthus suggests, whose representation, although they should not be censored, are also unworthy of praise.

It is not that reticent spectators are scandalized puritans or intolerant censors of his work on puberty, we are simply an informed public that does not live with its back to history, but conscious of the Western artistic tradition and the political burden that all aesthetic representation entails. Art is only a free experience when it responds to a privileged position. It is not, then, that “the panties of an adolescent [are] inciting to the sexual aggression of women” as Gabriel Albiac argues in this stupendous column on the occasion of the Internet petition that suggested the withdrawal of the Thérèse dreaming in the Metropolitan Museum or, at least, a contextualization of the work in reference to the possible perversity of its author. We are not asking for an iconoclastic attack on freedom of expression – as, indeed, the suffragette Mary Richardson executed in 1914 when she attacked Velazquez’s Mirror Venus as a protest against the government’s treatment of Emmeline Pankhurst. However, being able to show these “provocative” artworks does not mean that one should praise – as Laura Freixas rightly points out in reference to Nabokov’s Lolita – the self-indulgent representations of pederasty.

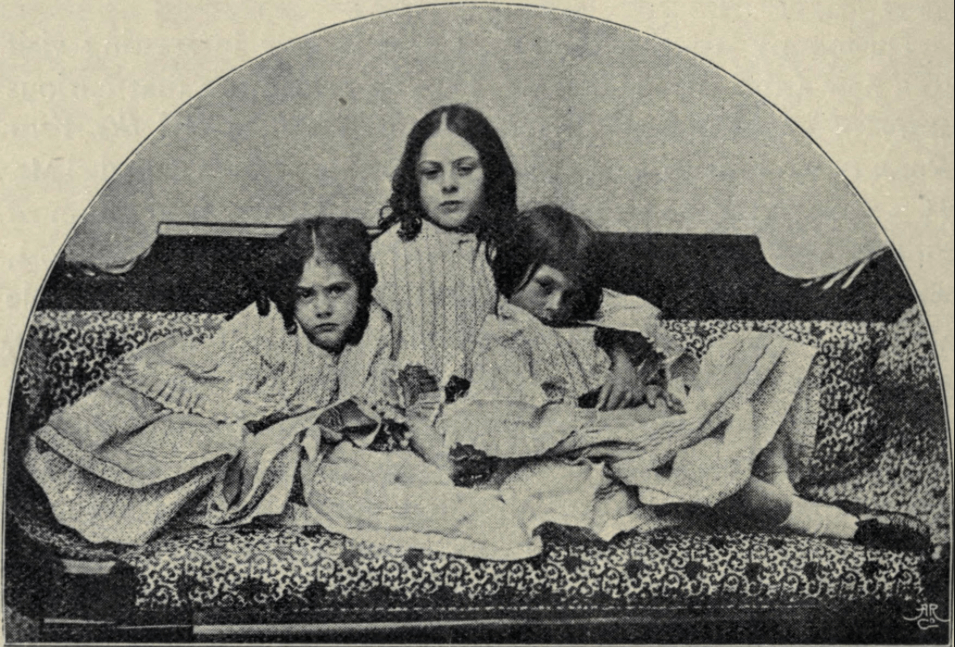

Through some feminisms we reclaim something much more modest and reasonable: we do not challenge the imaginative freedom of the artists, but the formative and pedagogical deficiencies in curating, museology and the history of art; areas that do indeed have the obligation to point out to the viewer the socio-political context in which the artworks were produced. Curators are not mere aesthetes, but mediators between the public and the artwork. In this sense, they fulfill a hermeneutic and didactic function. This is not about lecturing the public from the pulpit of art, but about engaging with modes of representation and their meanings. Let us expose the work of Balthus, the photographs of Lewis Carroll’s girls [13] or the homoerotic master-student relationships in classical Greece, but let’s do it explaining the power-truth-knowledge relationships that have allowed history to freely represent laudatory pedophile fantasies.

The claim of art as a sphere tangentially separated from its context, absent from all political or moral thought, is no more than the symptom of an asymmetric position of power. The problem is not the representation in itself of a sexed puberty – a theme that also appears in literary works by women such as The Lover by Marguerite Durás or Las edades de Lulú by Almudena Grandes – but rather the position of power from which it is expressed and, consequently, that frivolity with which they tried to show, contemplate and represent certain desires by representing them in candid artistic motives. It is that aristocratic spirit, of an uncritical bourgeoisie, of aesthetic dandyism, which stings in Balthus.

There is no conflict in the artistic execution of Balthus’s ambiguous work about puberty. He is limited to exposing and celebrating his fantasy with despotic distance, without criticism nor dilemma. What is distressing in Balthus’s work about female childhood is precisely that unlimited freedom that he allows himself, seeming to look at his desires over his shoulder, with absolute lightness, as if his desires were just naïve licenses of an artistic mood. Nevertheless, it is precisely the discomfort that this causes, where the undeniable artistic value of his work lies.

I am not scandalized by some “teenage panties,” but by that proud freedom to which a minimal moral conscience curbs, and also by the historical impunity with which certain power relations – the tiring erotic fantasy of the older man who has relationships with a minor – remains unquestioned – are socially tolerated, and remain veiled as delicious eccentricities or insubstantial signs of identity of the human condition. It’s not Balthus’s art that distresses, but the ideology that it sustains. Balthus’s masterpieces, in other words, are not merely artworks, but constitute a debatable way of being in the world.

Lead Image: Balthus (1944-1946), «Happy Days», Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Smithsonian Institution.

This article was first published on La Grieta. It was translated from Spanish by Marta Cillero.

[1] Lynda Nead affirms that the female body is “an icon of Western culture” and Mª Ángeles López Fernández maintains that there is a persistent pattern in the history of art: women acquire the status of object of the artwork, while that the male is the creator of it. See Nead, Lynda (1992): The Female Nude, London, Routledge, p. 14; López Fernández, Mª Ángeles (1989): «The woman and the portrait. An approach to the object », Art, Individual and Society 2, pp. 17-42.

[2] The information on the myth of Danaë is scarce in Metamorphosis, where only the following brief information is indicated in a passage: “Perseus, whom Danaë had conceived in a rain of gold.” See Ovid (2003): Metamorphosis, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, p.163. The general meaning of this myth has been extracted from Mavromataki, Maria (1997): Greek Mythology and Religion.Cosmogony, the Gods, Religious Customs, The Heroes, Athens, Editions Haitalis, p. 214.

[3] On the representation of Danaë in Titian, go to https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/danae-receiving-la-lluvia-de-oro/0da1e69e-4d1d-4f25-b41a -bac3c0eb6a3c

[4] Troisi puts it this way: «Klimt painted a resting Danae, with her face reflecting the ecstasy of an orgasm just reached». See Troisi, Alfonso (2017): The Painted Mind: Behavioral Science Reflected in Great Paintings, Oxford, Oxford University Press, p.17

[5] Munck, Jacqueline (2018): “On the threshold between dream and reality”, in Munck, Jacqueline (editorial director): Derain / Balthus / Giacometti. A friendship between artists (Exhibition held in Madrid, Mapfre Foundation, from February 1 to May 6, 2018), Madrid, Mapfre Foundation, p. 68-71. Munck highlights another tradition of horizontal women’s sense: the one that associates it with the mystical vision through the presence of Pathosformel as the head thrown backwards in the lying woman present in “Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy” by Caravaggio (1571-1610) ), “The ecstasy of Santa Teresa” by Bernini (1645-1652) or the representation of female hysteria in Les démoniaques dans l’art by Charcot and Richer (1887).

[6] Ovidio (2003): Metamorfosis, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, p. 211.

[7] García Expósito, Mercedes (2016): From the garçonne to the pin-up. Women and men in the twentieth century, Madrid, Cátedra, p. 69

[8] Ovidio (2003): Metamorphosis, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, p. 211.

[9] See Laqueur, Thomas (1990): Making sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, p. 160-178.

[10] Munck, Op. Cit., P. 69

[11] Ibid, p. 3. 4. 5.

[12] Original text in English: “For instance in Young girl in a blue armchair, 1878 by Cassatt, the viewpoint from which the room has been painted is low so that the chairs loom large as if imagined from the perspective of a small person placed amongst massive upholstered obstacle. The background zooms sharply away indicating a different sense of distance from that a workshop adult would enjoy over the objects to be easily accessible back Wall. The painting therefore not only pictures a small child in a room but evoke that child’s sense of the space of the room ». Pollock, Griselda (1988): Vision and Difference. Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, London, Routledge, p. 65

[13] Manuel Vicent in this column makes the following reading, away from eroticism, from the photographs of Lewis Carroll and his relationship with Balthus: «Balthus tried to imitate Lewis Carroll, who had managed to extract the deep and primitive, innocent secret and unknown, the essence of the angel, the soul of the girls. Against the attacks that accused him of being satisfied with the eroticism of these nude adolescents, he claimed that he intended just the opposite, surrounding them with an aura of silence and depth, creating a vertigo around him ».

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)