For decades, countries that were formerly part of Yugoslavia have been politically, economically and culturally intertwined; a shift in one neighboring country has rarely gone unnoticed in another. Such is the case with the region’s LGBT movement, with pioneers never failing to mention that personal, as well as professional relationships, along with a strong sense of community, helped create a strong bond between activists all around the post-Yugoslav space.

When change began to feel tangible in one county, activists from others would flock in to give a helping hand, as well as to learn and to feed off of the products of their courage and vigor.

It’s a theme that is present in different stages and decades of the feminist and LGBT movement in this region, whether we are talking about the first Yugoslav feminist gathering, Belgrade’s 1978 ‘Drug-ca žena’ (‘Comrade Woman’), or the first Pride Parade in the region held in Belgrade in 2001.

Early activism

One of the fundamental conditions for a gay and lesbian movement to emerge in the region was the decriminalization of homosexuality, which first occurred in Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro, as well as Serbia’s autonomous province of Vojvodina, in 1977, as part of wider legal reforms in Yugoslavia.

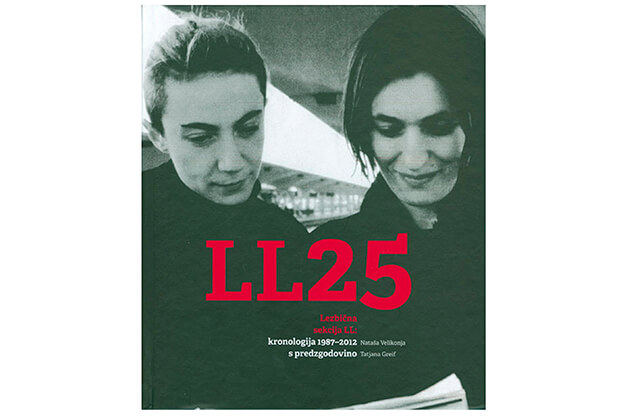

“It is only after that that homosexuality was able to enter public discourse and public space,” says Tatjana Greif, an activist and one of the authors of “LL25,” a history book on the Slovenian lesbian movement.

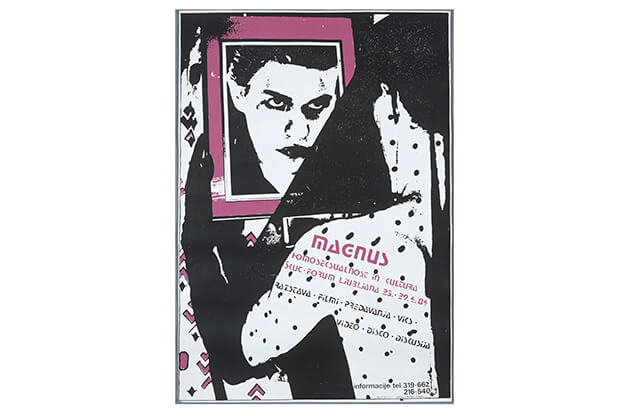

The first notable LGBT activism in the region was organized in Ljubljana in April 1984, when the students’ cultural center, SKUC Forum, put on the Magnus Festival that included films, exhibitions of gay publishing, and lectures and discussions on gay culture. Later that year, a group called Magnus, which embraced both gay men and lesbian women, was constituted as a section of the SKUC Forum, becoming the first LGBT group in the region.

Slovenian activists continued to be at the vanguard of the LGBT movement in its early years in the region with lesbian activism in particular beginning to find its feet within the counterculture scene. “Since the mid 1980s lesbian activism in Slovenia was a constituent part of alternative culture and the so called New Social Movements oriented toward the establishment of modern political culture and civil society,” Greif says.

It was here that the first lebian association in Yugoslavia — or indeed anywhere in Eastern Europe — was established. Based on feminist ideas, and evolving out of the existing feminist group Lilit, which had begun in the mid-1980s, in 1987 a lesbian section of SKUC was formed called SKUC LL (Lesbian Lilit).

“LL’s activists were engaged in the earliest phase of the feminist movement in the former Yugoslavia and today we are still building a lesbian and LGBT movement on principles rooted in feminism, emancipation, gender equality, equal rights and social justice,” Greif says.

Toward the end of the decade, this early activism also encouraged similar movements in parts of the region. With strong connections to SKUC LL, a group of women came together in 1989 to form Croatia’s first lesbian organization, named the Lila initiative, while feminist actions and ideas also helped to sow the seeds of lesbian activism in Serbia.

“The first organized encounters between lesbians in Belgrade were held by a feminist group called Women and Society after Yugoslav feminist gatherings in Ljubljana [in] 1987 and later in Zagreb [in] 1988,” says lepa madenovic (who intentionally writes their name in lowercase), one of the pioneers of the Yugoslav lesbian movement.

“Those encounters signified a break from heterosexuality as a norm and our only choice,” mladenovic says. “We looked for each other in order to realize who we are as lesbians in a world filled with hate towards women and toward women who love women.”

In Slovenia, SKUC LL began to co-found various cultural and social projects and also came together with the gay men’s group Magnus to establish the political association, Roza Klub, before once again returning to autonomous lesbian activism in 1997. At this point it opened a number of projects that, according to Greif, are still ongoing today. “[They] address both the LGBTI community and the general public through socially engaged activism, political activism as well as cultural activism,” Greif says.

Political upheaval

Just as lesbian and gay activism in the region was beginning to find its feet, in Croatia and Serbia came the political turmoil and wars of the early 1990s.

Interviewed in 2014 as part of an extensive article on 25 years of the Croatian LGBT movement for prominent Croatian LGBT news site CroL, Nela Pamukovic, one of the women who started the Lila initiative, explained that they were unable to continue their work in the new political climate.

“When the war started some women backed away for personal reasons, some because of the wartime conditions,” Pamukovic said. “It just wasn’t possible to pursue that kind of political activism.”

However, some of the women who had been involved in the Lila initiative became active in other organizations and initiatives. In 1992, Lezbijska i gay akcija (Lesbian and Gay Action, LIGMA), the first Croatian organization that was recognized as a gay and lesbian group, was started but due to the political circumstances its work was limited; its biggest success was its magazine, Speak Out, published within the magazine of the anti-war campaign and the first of its kind in Croatia.

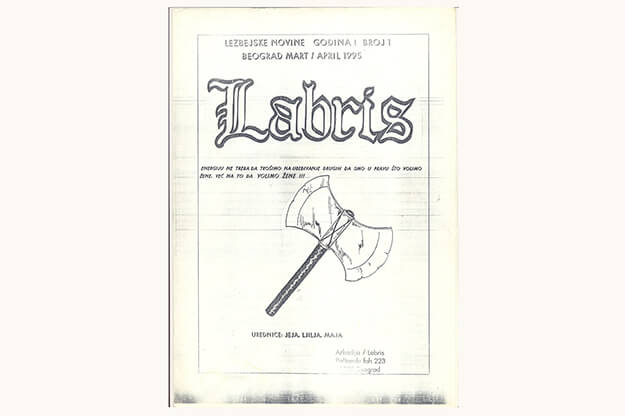

In Serbia too, activists diverted their efforts during the war years, with the lesbian and gay movement also interconnecting with the peace and feminist movements in Serbia’s increasingly radicalized political landscape. “A lot of us became anti-war activists,” remembers mladenovic, referring to organizations such as Women in Black. “So our first [lesbian] organization … Labris, was organized after the war ended in Bosnia and Herzegovina in November 1995.”

In 1991, mladenovic also helped to found Arkadija, a group that fought for the affirmation of both gay and lesbian rights, with the main aim of pushing for the decriminalization of the homosexual act.

This was achieved in 1994, although it is thought to have happened more incidentally than as a result of external pressure, as Serbia was changing different elements of its Criminal Code during its wars with Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Also around this time, mainly as a result of international pressure, Albania, Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina decriminalized homosexuality, bringing them in line with the rest of the Western Balkans in this respect by the mid-’90s. However socio-political conditions and the hardships that gay and lesbian activists throughout the region had to endure were enormous.

LIGMA, the only registered gay and lesbian group in Croatia at the time, ceased to exist in 1997 and its leaders emigrated to Canada and Sweden, where they were granted asylum due to the threats and attacks they were subjected to at home.

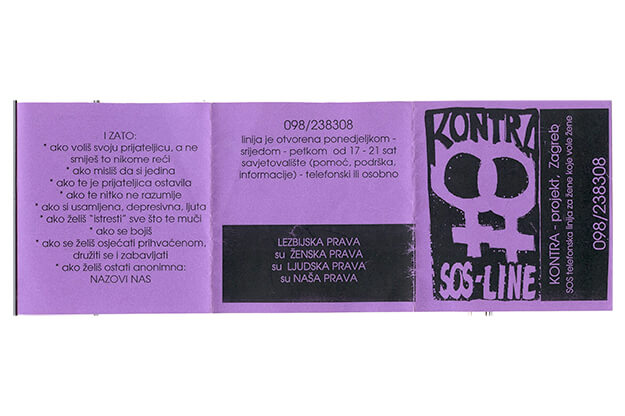

The same year, the informal anarcho-feminist group Kontra — which would later change its statute and become a registered lesbian organization that still exists today — was formed. Just a year later, in 1998, Croatia had a major legal breakthrough when the age of consent for homosexual sexual activity was equalized with that of heterosexual activity.

Following the death of President Franjo Tudjman in December 1999, and the subsequent downfall of his nationalist HDZ party after 10 years in power shortly after, the political climate in Croatia began to change. A lesbian organization, LORI, was able to register in Rijeka, and a new gay organization emerged called Iskorak.

Into the 21st century

Just as the millennium was about to turn, a shock wave was sent through the whole LGBT movement in the region. Dejan Nebrigic, Serbia’s first openly gay activist and one of the founders of Arkadija, had repeatedly complained to police about threats that he had been receiving, but they had refused to intervene. On December 29, 1999, the day of his 29th birthday, he was murdered in his apartment.

Then, 18 months later, in the summer of 2001, the intimidation and violence suffered by LGBT activists was laid bare for all to see. On June 30 the first regional Pride Parade — organized by Labris and the newly formed group, Gayten — was due to be held in Belgrade under the slogan, ‘Ima mesta za sve’ (‘There’s Place for Everyone’).

But the parade never took place. As activists gathered, they were violently attacked by big groups of organized hooligans, right wing organizations and members of the Serbian Orthodox Church, with the police that were assigned to protect them failing to provide adequate security. It was the start of a troublesome history of Prides in Serbia.

A number of Croatian — mostly lesbian and feminist — activists who had participated in the Belgrade Gay Pride decided that it was time to hold a Pride march in Croatia. Organized by Iskorak and Kontra, on June 29, 2002, the first Croatian Pride was held in Zagreb under a slogan that incorporated the names of the organizers – ‘Iskorak KONTRA predrasuda’ (‘Coming Out Against Prejudice’).

Around 200 people participated, but they were met with a huge number of protestors and vicious insults as they marched and as the parade reached its final destination a can of tear gas was thrown into the participants from the crowd; later that day and night it was reported that dozens of people were beaten and police arrested dozens of hooligans.

Later that year, an informal organization called Zagreb Pride was formed and it would later become the biggest and most influential LGBT group in Croatia. Then, just a year after the first Pride march, in 2003, the same year that Croatia applied for European Union membership, a law giving legal recognition to same-sex unions was passed, but it was derisible in its scope, giving same-sex couples just two rights as opposed to the 60 plus that are afforded to heterosexual couples.

Meanwhile in Serbia anti-discrimination legislation was introduced in 2009, which included discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and transgender status in all areas. In 2012 the Criminal Code was updated to include the concept of ‘hate crime,’ which applied to sexual orientation and gender identity.

But the technical changes on paper did little to mask limited political will to foster meaningful change. After the traumatic first Pride experience, and lacking the support of authorities who said that they could not guarantee participants’ safety, activists were unable to hold parades again for years.

That changed in 2010, when Belgrade hosted its second Pride, but it was again violently attacked, as was a Pride event the following year in Croatia’s second city of Split, where thousands attempted to violently disrupt the parade.

Such attempts to break the spirit of activists, however, failed. Despite being banned in Serbia between 2011 and 2014 by authorities citing a whole host of reasons, Pride has once again returned to the streets of Belgrade, while in Croatia, the event it today held annually in its two biggest cities.

Growing pains

While Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia can trace the routes of their LGBT activism back for decades, in other parts of the Western Balkans the movement began much later.

“The beginning of LGBT activism in Bosnia in Herzegovina goes back to the first civil society that concerned itself primarily with the rights of LGBTIQ persons — Organization Q,” says Lejla Huremovic, an activist from Sarajevo Open Center, which is today the biggest LGBT organization in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “Before the formalization of Organization Q in 2004, it’s important to mention, a lot of initiatives were started, but didn’t manage to stay alive.”

Organization Q itself only lasted for five years, closing its doors in 2009, the same year as the passing of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Anti-discrimination Law, which included sexual orientation and gender identity.

“In that period the most important event that occurred was the organization of the first Queer Sarajevo Festival (QSF) in 2008,” Huremovic says. “Sadly, the festival was violently stopped when a large group of Wahabists and ‘football fans’ started to protest in front of the Academy of Arts and verbally and physically attacked the visitors of the exhibition that was part of the QSF.”

The festival was not only a breaking point in the history of Organization Q, it was and still is, a turning point in the LGBT movement in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with Sarajevo Open Center being founded shortly after, in 2010.

“Since then a lot of initiatives have risen up and a lot of organizations have been formed and not only in Sarajevo but, for example, in Banja Luka, Mostar, Tuzla and Zenica,” Huremovic says. “Up until today we have managed to change a lot of the legal framework, we’ve managed to enter some of the state institutions and to work with them on matters of importance.”

In 2014 however, LGBT activists suffered another shocking attack, this time at the Merlinka Festival in Sarajevo, which had been put on to promote LGBT culture. Fourteen masked attackers violently entered the club where the festival was being held, injuring two people.

“I truly believe that the LGBT activism in Bosnia and Herzegovina was shaped by the violent attack on Merlinka … as well the devotion to continue with the organization of the festival in the years after it,” Huremovic says, proudly adding that the most recent Merlinka festival in 2016 was visited by more than 500 people, making it the biggest LGBTI event in Sarajevo.

Increasing visibility

Violent attacks on activists are somewhat a feature of the history of the LGBT movement in the region. Over the border in Montenegro, activists and LGBT rights supporters were also subjected to abuse and violence when they held their first Pride events in 2013, first in Budva in July, then in the capital Podgorica in October.

Despite this, the first Pride march stands out as a turning point for the movement for Jovan Dzoli Ulicevic, who is today part of Montenegro’s first organization focused on trans, intersex and gender variant persons, Spektra. “It may seem obvious, but it’s still unquestionably true – the event that completely changed the LGBTIQ movement in Montenegro was the organization of the 2013 Montenegro Pride,” Dzoli Ulicevic says.

The slogan of the pride was ‘Crna Gora ponosno’ (‘Montenegro – With Pride’) and its main symbol was a moustache. “We decided to shake up and take over one of the most patriarchal symbols of our country, which led to a very public and media exposed reaction of many of Montenegro’s citizens,” Dzoli Ulicevic says.

“People that were known for their moustaches started to shave them off. By taking over patriarchal symbols and by questioning gender norms, stepping into [public] space that was always reserved for the Montenegrin machismo, we questioned and exposed the traditional values – that was the breaking point.”

By this point, Montenegro had already passed anti-discrimination legislation with the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in the 2010 Law on Prohibition of Discrimination.

Montenegro’s southern neighbor, Albania, did likewise the same year and in 2013 amended its Criminal Code to define crimes motivated by sexual orientation or gender identity as hate crimes. However for both Montenegro and Albania — and indeed for countries that have made similar reforms throughout the region — legislative reform, which has been strongly pushed by international bodies such as the EU, has had little noticeable impact on the ground.

The Rainbow Europe Map, an annual review of the human rights situation of LGBTI people in European countries that is published by ILGA Europe, notes: “Albania is a prime example of the difference between laws on paper and realities experienced by LGBTI people in their daily lives.”

As with other countries in the region, the actual state of LGBT rights in Albania is shaped and influenced by the strength and visibility of NGOs that are focused on the improvement of LGBT rights in their home country. Annual Pride parades have been organized in the capital Tirana since 2014, but the most noticeable shift in activism here was witnessed in 2009 when, led by Kristi Pinderi and Xheni Karaj, the LGBT community started to wake up and act.

“Posters trashing homophobia were glued to lampposts, park benches next to government buildings were daubed in rainbow colors and walls were sprayed with pro-LGBTQ messages, often within sight of religious buildings,” NBC reported earlier this year.

Strength and resilience

One country in which the genesis of the movement was a little different to its neighbors is Macedonia, where experienced activist from the LGBTI Support Center, Biljana Ginova, says there has been 15 years of LGBTI activism.

“People that were active in the first organizations didn’t talk form their own experience, but they started to ask important questions and demand answers about the state of LGBT rights in Macedonia,” Ginova says. “In that fragile political context they created a base for all of us that came after them.”

A number of LGBTI organizations have since sprung up over the years, producing research and analysis, public awareness raising campaigns for LGBTI rights and against violence, and also cultural projects and festivals. But while other countries in the Western Balkans amended legislation to provide more protections to LGBTI persons as part of efforts to move toward EU accession, Macedonia’s European path nose-dived under the 10-year regime of Nikola Gruevski, and LGBTI persons are still afforded no protections under Macedonian law.

Despite this, Ginova is still positive about the progress that has been made. “I can say that, even though we still don’t have enough legal recognition or protection — mostly because of the political context that we’re in — we have still achieved a lot,” she says, before pointing to the forming of a new administration earlier this year as an opportunity to push on.

“We believe that we finally have a government that is willing to work with us on bettering the life conditions and the legal recognition of LGBT people in Macedonia. Work on an antidiscrimination law that is supposed to include sexual orientation as well as gender identity has already begun and should be concluded by the end of this year.”

Ginova also suggests that there are indications that the new administration is willing to consider changes to Macedonia’s Criminal Code in order to recognize hate speech and hate crimes in the future.

“Our activism has matured, we’ve tried different approaches and forms of activism and have reached a new level, started a new stage in our fight,” she says. “In this new climate, in the post regime system, we’re perceived as partners. We’ll see how things will unfold in the future, for now all we have is a small movement and huge potential for change, for making lives better for the sexual and gender minorities.”

Such optimism seems evident across the movement throughout the region. “Members of the LGBT community and the community itself grows stronger every day,” says Lejla Huremovic from Bosnia and Herzegovina, where in the last couple of years the LGBT community has started to undertake actions in order to be more visible on the streets. “It makes me happy to see that and it makes me happy that it’s happening all over and with more and more organizations and initiatives.”

Never-ending story

Activists know better than anyone that such positivity and proactivity is going to be essential as they continue to fight against deeply ingrained societal prejudice. Even the much vaunted EU accession — which is often held up throughout the region as the instant answer to all problems — has proven to be no guarantee of protection of LGBTI rights.

EU mechanisms that have been used in the precession phase such as insistence on reformed legislation have also been accused of putting form before substance, as once a country has joined the EU the rights of LGBTI persons are left to the whims of its government.

In Slovenia, which adopted an Act on Same-sex Partnership in 2004, the year it joined the EU, two subsequent public referendums — in 2012 and 2015 — turned down marriage equality for LGBT people.

But in Croatia, there has even been backsliding on rights since the country joined the EU.

In December 2013, just five months after Croatia was welcomed into the European Union, a referendum was held on whether to change the definition of marriage in the Constitution to a union between a man and a woman. It came about as a result of a campaign led by a neoconservative group In the Name of the Family — inspired by similar movements in the USA and France — which received the enthusiastic support of right wing parties and the Catholic church.

On a turnout of less than 40 percent, two-thirds of voters approved the change to the Constitution, which was subsequently made the following year.

However, due to strong resistance within the LGBT community, as well as human rights oriented Croatian civil society organizations, this retrogressive move only served to strengthen the movement. A platform for stronger cooperation was born and, after years of strong advocacy from LGBT organizations such as Zagreb Pride, in the same year, 2014, the Croatian Parliament passed the Life Partnership Act, making same-sex couples equal to married couples in everything except adoption rights.

The ongoing concern is that without widespread attitudinal change, such achievements remain as very much a victory of form over substance. Ana Brnabic’s appointment as the prime minister of Serbia, which the Guardian described as a “double first for the EU-candidate state,” is seen by many as the latest example of this.

For substance to prevail, and to tackle homophobia and transphobia, the strong, proud and unwavering voices of LGBT activists that stand up for themselves — as well as regional cooperation against a common oppressor of different minority groups that deny human rights — will be crucial in the future, as it has been in the past.

A lot has been accomplished, but there is much more to be done.

* This article was first published on Kosovo 2.0

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)