Valletta is the co-capital of culture for 2018. As with other similar occasions, the event offers the opportunity for the country to showcase itself internationally. On such occasions, officials tend to seek for ‘authentic’ and stereotypical images to present our ‘Malteseness’. Most of these images range from the nostalgic and romantic semi-rural past, to that of the Knights of St John and their city/ies ‘by and for gentleman’ around the Grand Harbour. It is a Malta made up of simple, laid back, people who uphold solid values and/or of chivalrous Knights. It is the Malta of Żepp u Grezz, characters of Maltese folklore, clad in what is considered to be traditional Maltese dress, that are frequently used to represent ‘Malteseness’. The emphasis on the Triton’s Fountain during the Capital of Culture opening ceremony was arguably the only exception from these stereotyped images.

Malta’s catalogue images involve a contradiction between what we are and how we project ourselves.

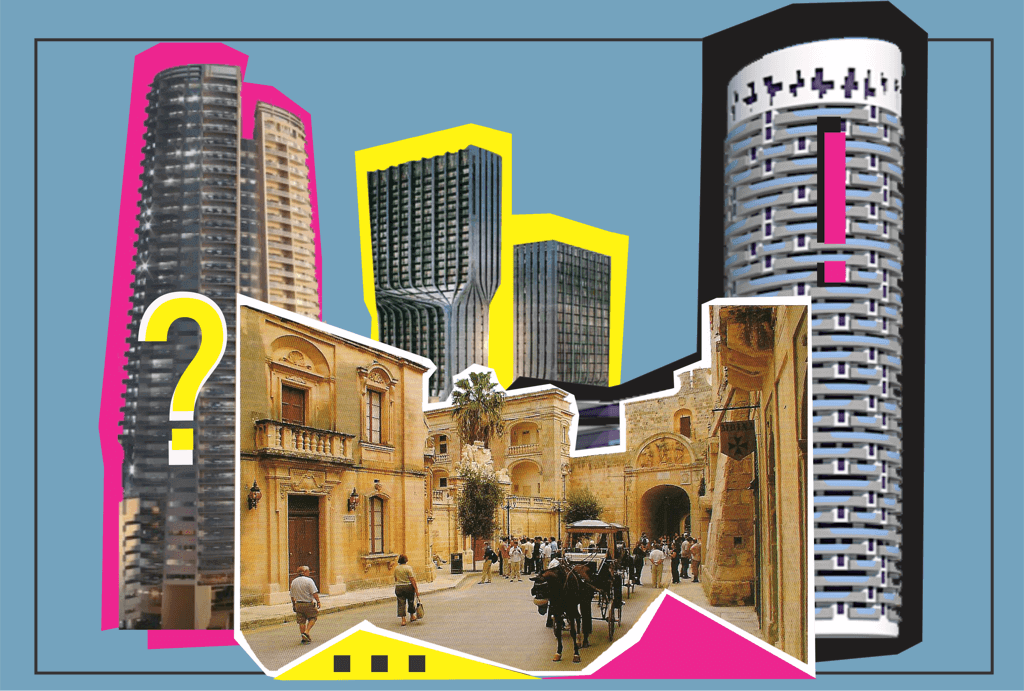

There is nothing extraordinary in this. Most countries present themselves through stylised, romantic and trimmed images. Yet, if one looks at how everyday Malta is, they will inevitably notice a discrepancy between the Malta that is represented in these romantic pictures and real Malta. Everyday Malta is becoming ever more a society where the neoliberal ethos, typical of the contemporary phase of capitalism, dictates the people’s rhythms and lifestyle in a way that is antithetical to the solid, simple and laid-back Malta of brochures and fliers. Malta’s catalogue images then, involve a contradiction between what we are and how we project ourselves; between how we generally consider ourselves and how we really are/are evolving. Understanding the contradictions between the Malta of adverts and the Malta of the mundane, sheds light on the ongoing social and cultural conflicts in the contemporary Maltese society. The rest of the article focuses on the aspect of this contradiction that concerns the organisation of space and built/rural environs.

Postcard Malta vs the Real World

Starting with the Nationalist administration of the 90s and followed more convincingly by the current Labour government, Malta has followed one model of economic development; a model that resulted in an economic set-up where manufacturing industries (since the 50s, one of the three pillars—together with services and tourism—of the soon to be born Maltese state) are still present but are in gradual decline. Construction is one of the few thriving labour-intensive industries, since gaming and financial services have shifted to the center of the economic set up.

Apart from the economic drivers of the construction boom, the spate of hyper-modern buildings is also associated in the minds of many with ‘progress’ and ‘modernity’, wherein ‘modern’ and/or ‘progressive’ are thought to require or instigate this type of built over-development.

The sprout of new buildings, constantly cropping up, have resulted in an array of (relative to our small country) high-rise and hyper-modern buildings scattered all around the island and not governed by a serious regulatory plan. They sit uncomfortably close to smaller and more human-scale dwellings. Even where village cores have been saved from development, the surrounding taller buildings have distorted the familiar skyline.

Malta does not brand itself as the place of ultramodern sky-scrapers.

Some of the effects of the construction boom have been dreadful, and not merely for aesthetic reasons. Those who are in search of property to rent or buy have experienced the negative effects of this upward surge in the property market. This rise in prices is the culmination of a trend—prices going up disproportionately, compared to wages—which, once again, began in the early 90s but rocketed in the last few years. Moreover, dwellings have become less spacious, green spaces have been eaten away and many neighbourhoods have become crammed and stuffed. All these aspects have had a major impact on the well-being of society.

In the past twenty years or so, Malta has been developing along one model, to the benefit of some and the (increasing) detriment of others, and with the blessings of both major political parties. Unlike places like the Emirates, however, which in relation to space and its content generally promote themselves as hyper-modern hubs—versions of Las Vegas in the Persian Gulf—Malta does not brand itself as the place of ultramodern sky-scrapers. Instead, the country is portrayed through images that highlight its idyllic Mediterranean location, rural lifestyle or its ‘glorious past’. This Malta, promoted in tourist catalogues (Mediterranean, ‘genuine’, Malta seems to be more marketable), but also internally radiates its Żepp u Grezz heritage through advertised architectural legacies, be these village cores or walled cities.

The elements of such idyllic pictures that correspond to reality however, are being systematically assaulted by the continuous development. It seems, we are uncomfortable with the emerging Malta, to the extent that we promote ourselves as being something else. A contradiction if ever there was one. A contradiction that in relation to some sectors like tourism has generated a vicious circle. On the one hand, we use the Żepp u Grezz images to attract tourists, while, on the other, the tourism boom propels further construction of hyper-modern hotels and tourist lodgings which are destroying the heritage used in the advertisements.

By way of conclusion: Some suggestions

Contradictions are normally conceived in negative terms. Yet, contradictory phenomena may involve tensions and pressures which individuals and groups that are committed to emancipatory politics should understand and exploit. Malta adopts a model of development in relation to the economy and to the rural/urban and human environment, but then those in power present a diametrically opposed picture of who ‘we’ are and what ‘we’ are becoming.

We seem uncomfortable with how we are evolving, and imaginatively hark after the human-sized and tranquil lifestyle that the pictures reproduce. Those who want to maintain the status quo try to mitigate this tension by supporting, endorsing or promoting cosmetic initiatives that conserve remnants of the idyllic pictures, while concomitantly sanctioning the current model of development concerning built environments and the economy of which it is a part. For instance, villages like Qrendi and Dingli have been recently awarded the badge of destinations of excellence for initiatives concerning the protection of Wied tal-Maqluba (the former) and the village square (the latter), yet the spate of apartments cropping up in both localities goes unabated.

Contradictions are normally conceived in negative terms.

Individuals and organisations committed to emancipatory politics concerning the environment should foster and exploit these contradictions to push their emancipatory agenda. They should highlight and exacerbate the tensions in way that steers clear between the Scylla of nostalgic nationalism and the Charybdis of accepting the current form of development.

Such political-environmental initiatives should recognise that the phenomenon of over-construction, which is antithetical to tranquil and human-scale development, is not born in a vacuum. It has very concrete roots and causes, and is not the sole responsibility of individual politicians. Ever since there was a decline in manufacturing, construction has increased its role in the economy and played an ever more important role in setting the economic wheels in motion. Conscious individuals and organisations who desire to change things radically should be aware of this and propose alternative economic and social strategies that go beyond moralising or single issue initiatives, important as these initiatives may be. Regarding the latter, groups and interests who stand to gain from the retaining the status quo and the politicians who represent their interests can afford to lose a pawn to win the game in the long run.

A concrete and feasible green economic plan for Malta; a plan that, amongst other things, envisions an economy that breaks from dependency on construction, is an urgent must. Taking a militant middle ground, which is informed by our past, and a proactive long-term vision is the way forward.

This article was first published on Isles of the Left.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)