Let’s start with the United Airlines video. The footage – which shows a Chinese doctor screaming in agony while being dragged off a United Airlines plane – has caused a national outrage. The end of the American dream of customer service was caught on camera, revealing a major violation of the main social rule of capitalism: the customer is always right.

Of course, this rule is based on the 1945-1970 era, when a moderately unregulated market seemed to benefit and build the middle class. This 30 year period within the entire 300 years of (modern) capitalism proved to be – according to Tony Judt and Thomas Piketty – an exception to the rule, a consequence of the Old World’s big meltdown (along with its capital) during World Wars I and II. Europe stopped competing, well, pretty much anything, which has made the American century possible.

Just as melting icebergs are symptoms of climate change, shitty customer service is a harbinger of the upcoming reality of “the 1 percent.” In the first year of the post-2008 recovery, 93 percent of all income gains went to the top 1 percent. And almost half of the world’s wealth is owned by the same mere 1 percent of the population. If the Trump Administration’s deeply regressive tax proposal is passed, this trend will inevitably continue.

No matter where it originates – land, dying industries, inheritance, or technology –the modern financial market is where capital really starts to reproduce itself. Capital having the ability to reproduce itself then marginalizes the need for required labor; labor becomes cheap.

They’ve made/ inherited money which means, to an American mind, that they’ve done something right.

Exacerbating these issues is the invention of hands-free and speedy-moving capital – which provides plenty of time for its owners to get involved in politics: the Koch brothers on one side, and Wall Street Democrats on the other. They’ve made/ inherited money which means, to an American mind, that they’ve done something right. Now they want to help the rest of us. Trump will transform our small businesses into empires, and Ivanka will help working women to scrub McDonald’s floor even harder.

The separation between politics and religion – even if never fully executed in practice– is probably the one claim to American exceptionalism. However, what the Founding Fathers couldn’t have predicted in the dusk of the 18th century was the need for a separation between politics and business. Washingtonian K Street is paved with good intentions, and lobbying – this twisted idea that you can apply capitalism to politics – makes sure that the status quo remains intact. The presence of money in American politics is so tiringly ubiquitous that we feel it’s pointless to complain about it. The sky is blue, the roses are red, and we spent $6.8 billion for the 2016 presidential election, right? Even those who believe that change is possible are busy gathering money – to drive money out of politics.

Every perception of every status quo in history is a psychological trick.

Every perception of every status quo in history is a psychological trick. Human beings are adaptable – which has good and bad consequences. The good is we are able to get accustomed to new circumstances quickly and thus have a tremendous survival rate – even Auschwitz. The bad, however, is that we seem to be able to get accustomed to anything – even Auschwitz.

Europe has rejected some ideas for a good reason. In addition to the revolutionary ideas that overflowed their boundaries, the ports of the New World took in some pretty damaged cargo: the immortal Vienna School of Economics; Ayn Rand; and – thank you, Max Webber – the ethics of Protestantism. Honestly, the only positive outcome of the Reformation was the fact that the Holy Inquisition chilled the fuck out. Medieval battles between the poverty of Christ and the money of the Pharisees ended with sweet divorce. Some protestants stayed, dealt with early capitalism, the birth of communism and the two world wars which exhausted Europe enough to direct it (even if briefly) towards social democracy. Radicals packed their bags and left for America.

No matter what you are trying to achieve, in the U.S. success always means – at least partially – financial success. After all, according to Protestantism’s ethics, your wealth is God’s reward and a sign that you are doing things right. Success is proof of virtue. Even with the increasing attention being placed on problems of economic inequality, American economic gurus are imperturbable in their deep conviction that the only thing that motivates people to strive for productivity and innovation is personal greed. One of the most overused epithets in the U.S. is “hard work,” something that seems to apply equally well to a toddler building sand towers (“Good job!”), Ivanka Trump “building” Trump towers, and a Mexican dishwasher finishing a double shift. We are obsessed with the idea of the self-made man. We are trained to admire the figure of a hedge fund manager – paranoid and blind to anything else but their own personal vendetta against the world. Taking five bucks from him is considered unfair treatment of him, and he also includes the government, market rivals, ex-wives, and coworkers. It feels unfair to him so it must be unfair – objectively.

Each person advocating for what she/he wants the most doesn’t make for a conscious democracy.

And here we touch the very core of our problems: American politics is driven by personal stories. An American politician will always tell you that he understands you, his voter, because his Uncle Willy was poor too, his dog died when he was four, and his grandma was an immigrant. Of course, he understands. Regular citizens make the same mistake: they choose the policies according to what benefits them personally and immediately. But personal choices are not actual political choices; each person advocating for what she/he wants the most (a Porsche, the neighbor’s wife, tax cuts) doesn’t make for a conscious democracy. It’s precisely because of this blurred line between what’s private and what’s public that we observe rich people feeling entitled to run the country. That’s why Trump is our president. He has money, therefore he’s a good businessman, therefore he’s done something right.

Making money. It takes a very long time – and most of us never get there – to realize that there’s nothing to understand here. Money is an abstract concept. It has no value other than a social one. And Wall Street is the cherry on the top of this abstractness, a true Kandinsky piece: you stare at this complexity and assume you lack certain powers for understanding it. But really, there’s nothing to understand; it’s just symbols and interpretation – an aesthetic pleasure. Or, rather – when we translate it to Wall Street – a bunch of dudes who know each other and make bets, who have means to make bets, and who do a lot of them at the same time.

Protestantism, the belief that God rewards you with money, has a contemporary secular analogue called libertarianism and renders people less sensitive to drastic social contracts. Of course, not every business manager is a narcissistic sociopath doing coke. The phenomenon of the sharks of Wall Street is supported by an army of Eichmanns. They do their job taking pride in their work performed, remaining within the letter of the law and responsibly delivering to their shareholders. The evil consequences of their everyday actions are completely removed from their everyday experience. They are good family men, good neighbors, they donate to political campaigns. They represent the banality of evil – consultants whose wisdom contains nothing more than personal-political connections and ridiculous management fads, and CEOs who smoothly land with their golden parachutes after running the company into the ground. What kind of hard work is that? What kind of expertise is that?

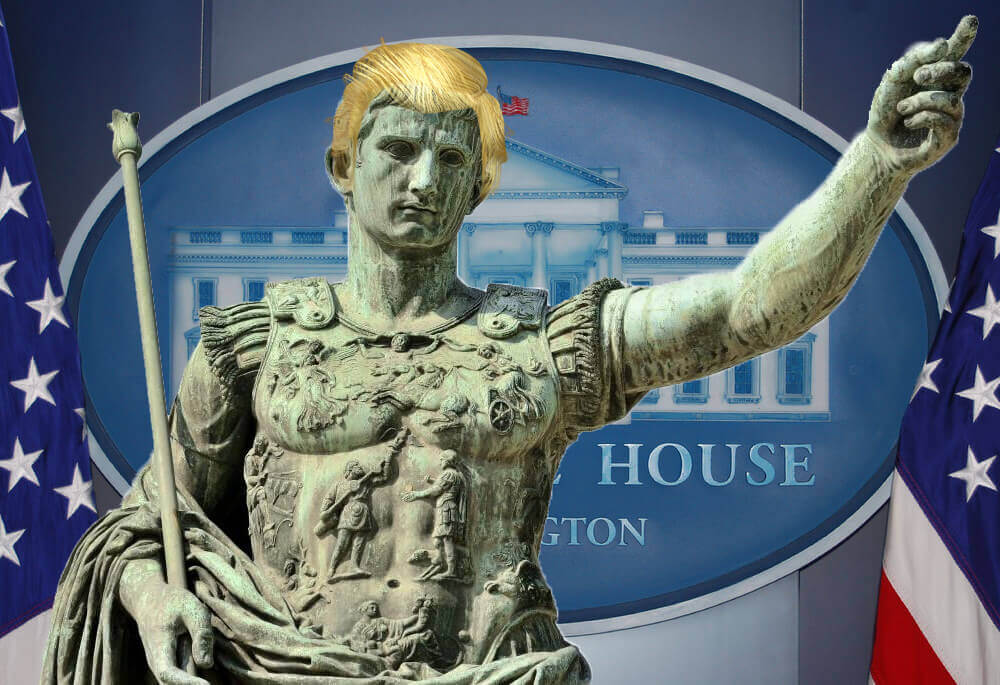

Both Trump and Caligula were beloved by the masses because they had no respect for the government and humiliated political elites.

The paradox of Donald Trump is a gift from an ironic heaven. A bucket of ice cold water on our heads. Finally, it’s in our face and we have a very strong motivation to disagree with the status quo. Things are so bad that we have a hard time believing them. We have Caligula in the White House. Yes, for a second I thought that I was being original here. To my delight, a historian, Tom Holland, and The Guardian, have already explored these parallels for us. Both Trump and Caligula were beloved by the masses because they had no respect for the government and humiliated political elites. Our executive branch conducts domestic and foreign politics according to who is nice to him. For the first time, we face the nakedness of politics, in which it has no shame or patience to hide its own impulsiveness and egotism.

At his side, we have Doctor Faustus (yes, I found a good literary metaphor to illustrate Paul Ryan’s problem as well). This good Catholic boy gone bad after being screwed in the head by Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman decided to make a deal with the devil. He cannot decide whom he despises more – a weakling asking him what’s going to happen to his/her health care, or the toddler-autocrat in the White House. Wall Street – which started out by throwing one hell of a party on expectations of massive deregulation and tax cuts – is trying to remain hopeful, but wakes up at 3am every night with a nightmare, only to binge read Trump’s latest tweets. They are dealing with a new element too: Trump, who is in this game mainly for himself.

In the meantime, United Airlines stocks are going down. The crisis of customer service in the U.S. is making the world flatter, which is resulting in the global economic war moving into U.S. territory. We are slowly beginning to realize that we all are idiots from Cleveland who took easy house mortgages believing in the American dream and hoping for the best. Sooner or later, we all will be carried out, screaming.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)