Social Democratic Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka was trying to save his face and the sinking support of his party when he announced the whole cabinet’s resignation on May 2. With only six months to go before regular parliamentary elections in October, the ruling Social Democrats know well that it won’t be them, but their coalition partner, the movement ANO [Yes], led by billionaire Andrej Babiš, who will be putting together the next government. The past three-and-a-half years have been marked by constant fighting between Sobotka and Babiš, his Finance Minister and deputy. Mired in one scandal after another, Babiš’s reputation seems immune to any of the accusations piling on him – his movement is currently polling at around 30%, leaving all other parties well behind. Now, however, Babiš faces accusations of large-scale tax evasion, as well clear indications he tried to influence media he formerly owned thanks to leaked recordings, circumstances the Prime Minister claims he could no longer igonore. Sobotka’s initial resignation can thus be seen as a final attack on his coalition partner and simultaneous foe. Providing an explanation on Wednesday of why he did not simply dismiss Babiš and keep the current government in place, Sobotka stated he did not wish to give the Finance Minister an opportunity to turn himself into a “martyr” and thus gain even more political sympathies from his electorate.

Among the Visegrad countries, the Czech Republic is usually seen as the one with the most functional democracy.

Before we go any further in following the chaotic events of the next days, let us remind ourselves who Andrej Babiš is and why Sobotka finally chose to confront him. Among the Visegrad countries, the Czech Republic is usually seen as the one with the most functional democracy. It has so far lacked an authoritarian leader who would openly curtail the system of democratic checks and balances as Kaczyński and Orbán have – and although President Miloš Zeman may well have such ambitions, his constitutional rights are too weak to seriously affect the course of the country. Neither is the extreme right marching in the streets in uniform, as it is in Slovakia and neighbouring countries.

The coalition of the Social Democrats, Babiš’s ANO, and its third, ineffectual member, the Christian Democrats, has ruled the country with stability, and apart from its stubborn refusal of refugee quotas, it has generally not given the rest of Europe a headache the way its neighbours have.

But let us not be deceived. On Political Critique, we have repeatedly written about the dangers presented by Babiš, who is almost sure to be the next Prime Minister. He may not have a nationalist-Catholic ideological project like his Polish or Hungarian counterparts, but his regard for parliamentary democracy is just as non-existent. Babiš’s motivation is more prosaic; as the second richest Czech citizen, owner of an extensive agricultural, chemical and food-processing conglomerate, as well as a number of large media (which he was recently forced to nominally transfer out of his own ownership thanks to a new law on conflicts of interest), he is sure to protect in the first place the interests of big business. Indeed, the slogan with which he gained support is that he will “run the country like a business”. And the kind of business Babiš does is not necessarily compatible with the rule of law, transparent financing, democratic processes, or the freedom of the press. It is, however, highly compatible with absolute pragmatism. Babiš has not yet reached to racism or “traditional family” policies to legitimate his political project, because he hasn’t had to – but who knows when they’ll come in handy. He is already close with President Miloš Zeman, who is hardly squeamish about stoking the most overt forms of racism, sexism and other types of hatred in order to gain the support of “anti-establishment” voters and generate political conflict in a classic strategy of divide-and-rule.

Zeman openly chose to pretend he had not received the most recent message and prepared a resignation ceremonial, together with a press conference, for Sobotka.

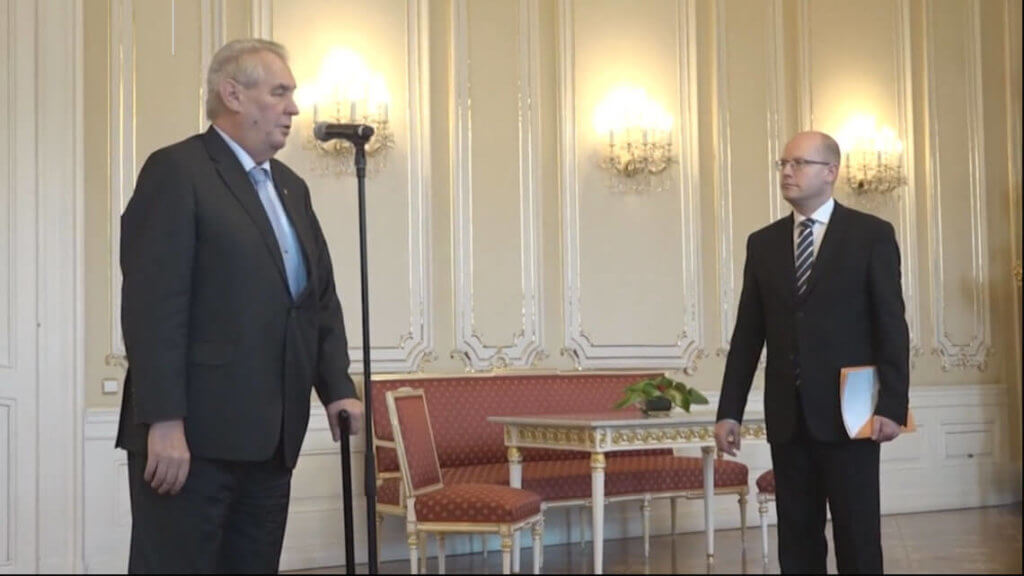

And it is Zeman who’s the real culprit in turning the current political crisis into a farce that not even the screenwriters of The Thick of It could envision. Having announced the cabinet’s resignation on Wednesday, Sobotka made his way to Prague Castle, the President’s seat, on Thursday – not to tender his resignation, as he announced that morning, but to first discuss the serious governmental crisis with the President. Zeman however openly chose to pretend he had not received the most recent message and prepared a resignation ceremonial, together with a press conference, for Sobotka. In effect, Zeman accepted a resignation the PM had not yet tendered. The Prime Minister, taken aback, was momentarily lost for words. To make his humiliation complete, Zeman vulgarly used his walking stick to point Sobotka to his place behind the microphone, moreover addressing him with the informal Czech equivalent of the French tu as opposed to the standard vous in official situations. The PM bravely held his ground, but once he started to speak about the cause of the crisis – Minister Babiš’s dodgy dealings, President Zeman, in an act of unprecedented rudeness, walked out of the press conference.

Watch the video here:

The President is absolutely open in his disdain for the Prime Minister and his support for Babiš in a gesture that lacks anything that could even vaguely be called political culture. While Sobotka made it clear he was willing to put together a temporary government until the elections, as long as it did not include Babiš, Zeman opined it was rather Sobotka who should leave, while he allegedly sees no reason for Babiš’s dismissal. Zeman, the President of a country which by law grants only ceremonial rights to the Head of State, leaving real power in the hands of the Prime Minister, is actively rewriting the constitution by his actions and constantly pushing the boundaries of the extent to which he can intervene in the day-to-day running of the country. Yesterday’s events were a highly dangerous precedent. And it looks like Sobotka’s attempts to outmanoeuvre Babiš will not meet with much success. The Zeman-Babiš pact will ensure that the country will soon be under the control of politicians whose respect for democracy is nominal at best.

The situation, however, continues to unfold. This morning, Sobotka withdrew the cabinet’s resignation and instead announced the dismissal of Babiš alone. Zeman’s reaction is still pending at this point. Even if Sobotka’s tactic of damaging the reputation of the Finance Minister did succeed, the Czech Republic finds itself between a rock and a hard place. Voters dissuaded from voting for the scandal-ridden Babiš will hardly switch to Sobotka’s Social Democrats, wallowing in disarray. Rather, those for whom the businessman Babiš represented an alternative to exhausted traditional politicians (much like Trump in the US), are more likely to give their vote to truly anti-systemic, largely extreme-right political groupings. It may thus not be long before the Czech Republic too has its uniformed nationalists marching through its streets.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)