“I do not have any choice. I cannot go back to Russia right now. I need to stay till … well … as long as Putin is President of Russia, nothing will change in Chechnya”. Mamud has been living in Poland for two and a half years. He comes from Gudermes, a Chechen town, around 40 kilometres from the capital, Grozny. His goal was not Poland but Belgium, where his aunt has been living for years. When he crossed the Polish border, he registered as an asylum seeker, but later on he decided to go further to Europe and not wait until his case was processed in Poland. Two months later, he was deported back to Poland where his case was reopened under the Dublin III Regulation. Even though he has not received official refugee status from the Polish state, he successfully fought to legally remain in Poland with the same rights that refugees are entitled to. Now he is taking part in a year-long integration programme that gives refugees time to learn Polish, find a place to live, a job, and to integrate themselves into Polish society.

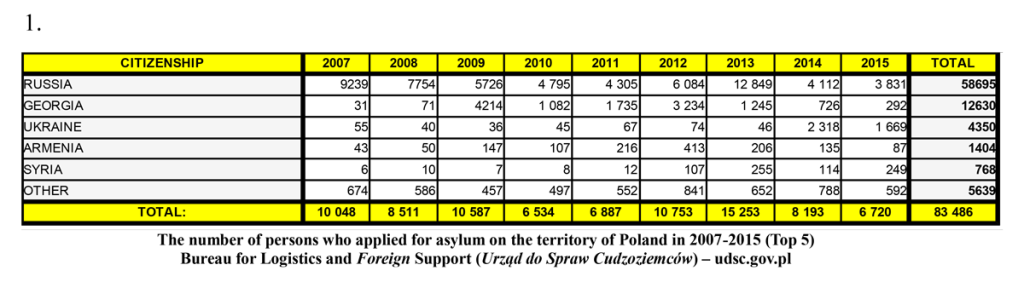

First, Mamud got a rejection from the Polish state, just like thousands of asylum seekers every year from the Chechen Republic, Russia, and countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Syria.

We are sitting in a cafe in the centre of Warsaw. The place is full of people mostly because of the chilly weather outside. What is most surprising is Mamud’s objective tone about his own and others’ stories. Recently, in the middle of the refugee crisis in Europe, people have tended to react with one of two principle emotions: compassion or hate. Mamud’s moderate behaviour can offer a better vantage point for seeing the problem of Chechen asylum seekers and refugees from two sides: the ongoing drama of Chechnya and the imperfection of Polish refugee policy. Even though Mamud only started the integration programme a few months ago, he speaks Polish fluently. “I did not want to wait until the end of the procedure, I decided to integrate myself”.

But in the beginning, it was not that easy for him. First, Mamud got a rejection from the Polish state, just like thousands of asylum seekers every year from the Chechen Republic, Russia, and countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Syria. Mamud is a lawyer by profession. He had to leave a high position in the Chechen political opposition movement when the situation escalated after the second Russian-Chechen war, aggravated by the brutality of the Russian-supported Ramzan Kadyrov regime. “I can say that if a person decides to go against Russia or the Putin-supported government in Chechnya, they can choose between two different directions: going to prison or dying”. Mamud mentioned a black list circulated in Chechnya with the names of people considered enemies of the Kadyrov regime. When I asked him if his name could be on the list, he nodded and said: “I do not only think that my name is on the list. I know it is”. This was the main reason he was determined not to be deported back to Chechnya. He even appealed to a Polish court after the rejection of his application. He was lucky. But most importantly, as a lawyer, he knew exactly what to do in his own case. From this point of view, Mamud’s story is an exception among thousands of asylum seekers who tried to reach Europe from Chechnya by crossing the Polish border. “Poland needs a modernization of its refugee and integration policy”. In light of the huge numbers of rejections, this could well be true. The story of these Chechen refugees is not only about the destruction and brutality of the Russian-Chechen wars and their consequences, it is also about the inadequacy of the Polish refugee policy.

Asylum seekers in a bad light

As a result of the current refugee and migrant crisis in Europe, the history of Chechen refugees is seen in a new light in Poland. They represent the most numerous ethnic group among people who applied for refugee status in Poland in the past 15 years and most of them are Muslims. The long history of Chechen Muslims arriving to Poland is not a new argument in Polish media and politics. It is referred to when people argue for the growing Islamophobic attitudes in the country and all over Europe. Sometimes tensions lead to violence, as they did in the northern Polish town of Gdańsk, where police clashed with protesters at the end of November last year. Even though Poland has not taken a large number of asylum seekers from Syria and Iraq (only a few hundred families so far) the “refugee problem” played an important part in last autumn’s parliamentary elections: during the last part of the campaign, the then-opposition party, PiS (Law and Justice), shifted the main emphasis of their criticism from domestic corruption scandals to the global refugee crisis, depicting it mostly in negative terms. However, it would be an exaggeration to say that PiS had won the election largely because of the refugee crisis in Europe. The main arguments presented during the campaign by the more conservative and Eurosceptic political parties focused on the potential danger arising from different cultures and religions that may threaten Polish and other European societies. This was not a new message. During the summer, a Polish relief-organization called Fundacja Estera helped about 60 Syrian families to move to Poland and start a new life there. They were lucky because they were Christians. According to the Financial Times, the president of the Foundation, Ms. Miriam Shade—who, during the election campaign, was one of the candidates of the far-left Eurosceptic party KORWIN—explained their decision by saying that Polish people are afraid of Muslims, but she has been reported to have also said that Syrian Muslims share the same religious views as so-called Islamic State (ISIS or IS) and that therefore they are safe in their own country, unlike those Syrians who are Christians.

Poland has been taking asylum seekers from Chechnya not only for reasons of solidarity but also with the intention of fully complying with European Union law, specifically the Dublin III Regulation.

The presence of Chechen refugees for about two decades attests to the fact that the arrival of Muslim asylum seekers to Poland is not a new phenomenon. Their case was one of the main arguments for the former governing party PO (Civic Platform) to defend against the attacks of their political opposition, especially when at the end of last September the PO-government agreed to accept around seven thousands refugees who had arrived in Greece and Italy. When still in office a few months ago, Ms. Ewa Kopacz said in the Sejm that “Poland took thousands of Chechen Muslims in the last two decades and there was no terrorist attack in the country”.

Mr. Grzegosz Schetyna (Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland from 2014 to 2015 and leader of PO since 26 January 2016) also referred to Chechen refugees as an example that shows Poland as a welcoming country in Europe: “…in the past twenty years, almost 90,000 Chechen refugees have come to Poland, as it was the first safe country they reached. We took them in, we showed solidarity, because Poles know what it is like to need help from abroad at times of need.” The numbers are realistic, and the larger part of Polish society seemed having shown solidarity. Additionally, there are two other factors which played an important role in this “welcoming attitude”. Firstly, the Poles’ mostly negative attitude towards Russia and their objection to the aggressive policies of Mr. Putin towards the former constituent states of the USSR. Poland’s own “experiences” with the USSR could easily reignite Polish solidarity not only with Chechnya, but with Georgia and Ukraine too. The other factor is not based on emotions. Poland has been taking asylum seekers from Chechnya not only for reasons of solidarity but also with the intention of fully complying with European Union law, specifically the Dublin III Regulation. According to the regulation, every asylum seeker who crossed the border of the EU needs to register him or herself in the first EU country where he or she entered the European Union. For Chechens that usually means Poland. However, the majority of them are not planning to settle down there at all. Poland is for them a transit state on their way to Western European countries like Germany, France, or Belgium. According to the Polish Office for Foreigners, during the course of twelve years, from 2003 to 2014, 272,000 citizens of the Russian Federation applied for refugee status in EU countries and 73,000 of them filed their application in Poland. Most of them come from the Northern Caucasus with Chechen nationality. Prior to the year 2000 (during and after the first Russian-Chechen war from 1994 till 1996), the majority of the applicants were young single men who wanted to work in Europe and create the basis of a new life for themselves and their families at home. In the following years, especially after the outbreak of the second war in 2004, more and more large families left their homes in Chechnya and travelled to Poland. Among the entrants there were a lot of children, but also single mothers. Most of them came from the Chechen capital, Grozny, and its surrounding districts. From the beginning of the second Chechen war, other people belonging to other ethnic groups from the Caucasus—Ingushis, Dagestanis, Georgians, Ossetians, and Armenians—also went to Poland. The majority of them came via Belarus.

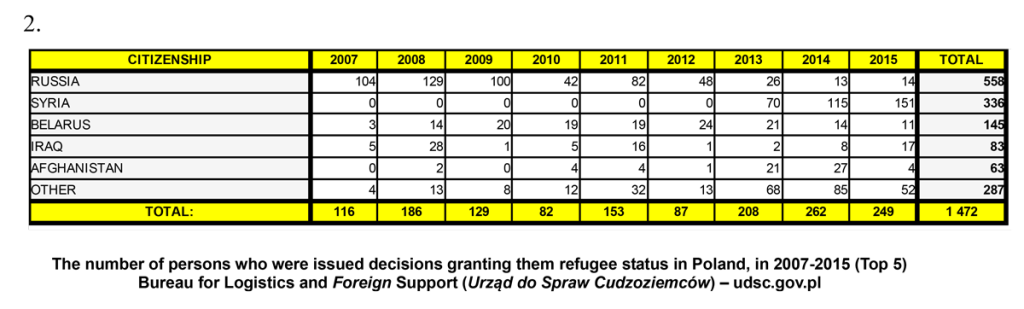

The main driving factor for them to leave their homes was the need to escape from regions affected by armed conflict. Officially, the second Russian-Chechen war ended in the 2009. Although the number of refugees has been getting lower year by year, thousands are still crossing European borders, mostly because of the brutality of the Kadyrov regime and the poor living conditions of their home regions. The biggest increase in the number of applicants arriving from the Russian Federation took place in 2013, when the German government agreed to introduce social benefits for refugees equalling the amount paid to German citizens. That year, Poland had taken 12 849 asylum seekers from the Russian Federation. As a comparison, consider that in the preceding year the number of arriving applicants was 6084, while in the year before that it amounted to 4112.

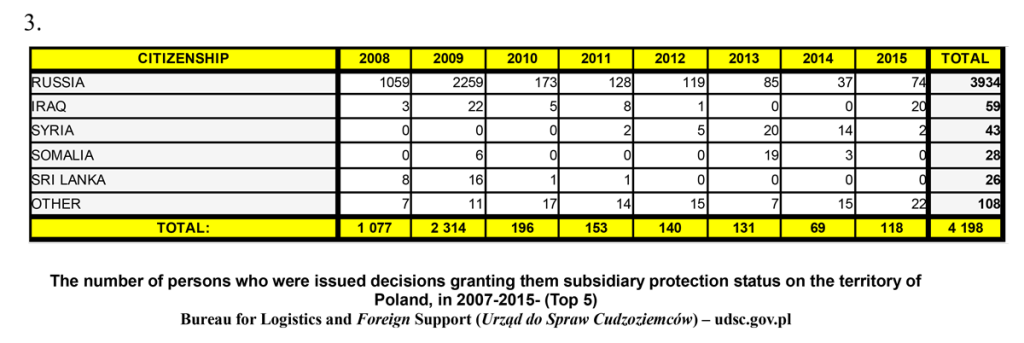

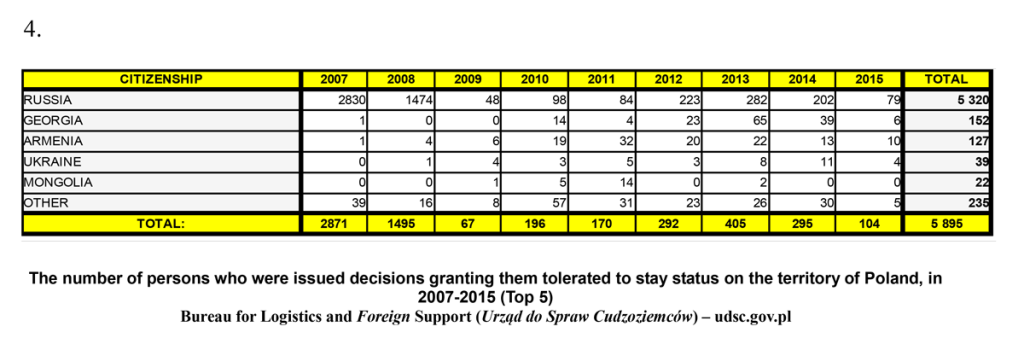

The number of positive decisions by the authorities was especially low that year: not more than 26 persons were granted refugee status. However, in Poland there are two further categories as well. One of them is the so-called “subsidiary protection” which is almost equal to refugee status. In 2013, eighty-five asylum seekers from the Russian Federation got this status. There is a third category called “tolerated stay”. Most of the third category positive decisions were granted to applicants whose overall number amounted to about 85 per cent of all those recognized to be in need of protection. Those who find themselves in this third category are not provided with integration assistance, but they have the right to make use of social assistance like access to the labour market, the right to pursue business activity, free access to elementary, grammar, post-grammar school, an entitlement to healthcare, and have the right to travel across the EU without a visa, etc. 282 persons got this status in 2013. In total, 393 asylum seekers managed to get a positive decision in that year, including 3 per cent of applicants from Russia. A few years earlier, the numbers were not as low: in 2008, 2662 refugees got a positive decision from a total number of 7754 asylum-seeking applicants from Russia, (that means 34 per cent of the applicants of whom 129 individuals were granted refugee status, 1059 individuals were taken under subsidiary protection and a further 1474 individuals could stay legally in the country).

In 2009, with the war in Chechnya having ended, the situation changed dramatically. The number of positive decisions was 321 from 5726 applications (overall 6 per cent: with 100 having been granted refugee status, 173 receiving subsidiary protection status, and 48 people were classified as entitled to “tolerated stay”). From 2009 on, most Chechen newcomers were no longer considered to be war refugees despite the brutality of the Russian-supported oppressive regime in Chechnya. Last year, the Polish state received 4112 asylum applications from Russia. The authorities approved 252 of them (Overall 6 per cent: with 13 granted refugee status, 37 granted subsidiary protection, and 202 granted temporary stay.)

“Those negative numbers are one of the main reasons why they do not wait till the end of their own procedure and leave Poland, moving to Western Europe after their registration even if they know that they could easily get sent back to Poland because of Dublin III”. Mr. Jacek Białas, lawyer of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights in Poland, said the official decisions in the case of the Chechens are problematic. “There are many cases which should have been considered positively in my opinion, but they got the rejection decision more than once”. The Foundation is not taking part in the integration process itself but it is trying to help people during their asylum request proceedings. After several rejections they can help them go to court, but according to Mr. Białas, it is not easy to convince the court to change rejection decisions. But of course there are also positive examples. Like in the case of Mamud, who was able to make the Polish state change the rejection to a positive decision. Mamud could stay legally in Poland but thousands of Chechen asylum seekers can only choose between two options: going to illegality in Western Europe, hoping that they won’t be deported back to Poland, or simply go back to their homeland.

Arrival and pre-integration

A lot of asylum seekers need to choose the option of leaving Poland after their registration process. Mr. Maciej Fagasinski, member of the non-governmental organisation Refugee.pl Foundation, told me he heard about a case in which somebody had tried 8 or 10 times to leave Poland and they would try again and again after every deportation. They simply refused to wait in Poland until the formal decision on rejecting their application was made and would continue to try to find an alternative solution which would allow them to join their family members in Western European countries. The Refugee.pl Foundation was only set up last year, but they have a long history of helping refugees and migrants in Poland. The foundation has three major projects: firstly giving legal advice to asylum seekers and migrants, secondly helping with the integration process by teaching Polish language and culture, and last but not least, educating Polish society (and journalists) about refugees and migrants via social media, like Facebook, Twitter and Youtube. Mr. Fagasinski highlighted the importance of the latest election campaign when politicians used the term “migrant crisis” in a very negative way. “They are creating bad stereotypes, using false language, creating irrational fear within Polish society. This is unacceptable and we are trying to fight against it, but, to be honest, it is very hard job to do.” According to Mr. Fagasinski, the refugees who are living in Poland are almost invisible. Mostly because of the numbers: only a few hundred people get refugee status or other kind of international protection in Poland every year. Secondly, those who decide to stay try to find their way to become part of Polish society somehow. And thirdly, they try to choose another solution to staying in Poland. Ukrainians, for example, are able to stay, as for them it is quite easy to get a Polish visa and with that they are able to settle down more easily, avoiding the long procedure of the refugee process.

Chechen refugees have avoided the mixing of “migrants/refugee” and “terrorist” categories which has come to characterise the discourse of receiving European countries.

The Refugee.pl Fondation, like many other NGOs cooperates strongly with reception centres. Currently there are 11 reception centres in Poland filled mostly with asylum seekers of Chechen origin. Two of them, Dębak and Linin, are near to Warsaw. The location could be a decisive element of the pre-integration process: for those close to bigger towns it is not so difficult to get to know Polish society. But the majority of the centres are located in the eastern part of the country close to smaller towns or villages where the inhabitants are not so open to newcomers. This unequal situation could severely hamper the integration process itself. There were a few scandals in the past as well. A few years ago Katowice (the reception centre in southern Poland), was closed mostly because the inhabitants were against allowing more asylum seekers to take up residence in the town. An almost identical situation occurred in the small town of Łomza, where tensions between mostly Chechen asylum seekers and local people escalated to the point where the Refugee Centre had to be closed in June 2010. Those asylum seekers who need to live in the centre of small eastern towns like Bezwola found themselves in the most difficult situation. The reception centre itself is located in the middle of a forest miles away from the closest village. “Without touching the host society it is very hard to be integrated … almost impossible” – said Mr. Fagasinski who added another serious problem too: the asylum seekers are not allowed to work in the first six months, which also contributes to making everyday life harder for them.

Collective sinfulness

According to Mamud, the most difficult time for an asylum seeker is the time spent in the reception centre. He stayed only 5 days, but most of the asylum seekers long months in a centre. He added there are no major problems between the different ethnic groups living together, but sometimes different kinds of tensions could reach a breaking point. A few months ago, Polish newspapers reported a quarrel between a Chechen man, a Ukrainian, and a Georgian women in the Linin reception centre. The man was complaining about the way they dressed. According to him, they were wearing too revealing clothes inside the centre which he considered to be a bad example for his daughters and against Islamic rules. The case would have been forgotten between the walls, but the loud dispute was recorded on a mobile phone. The women tried to explain to him that Poland is not an Islamic state, but the man simply did not want to accept these arguments. After the record was made public, the Polish far-right media tried to make use of the incident to label all Chechen Muslims negatively, but without success. Discriminating against Chechen refugees has never been as serious an issue as the current refugee crisis. After the Paris terrorist attacks, the lives of refugees from the Middle East travelling through Europe became extremely hard. Interestingly, Chechen asylum seekers and refugees were not labelled as terrorists after the serious terrorist attacks that had been carried out by Chechen extremists in the first half of the 2000s: the Moscow theatre attack in 2002 with 170 dead people, the Moscow metro bombing in 2004 with 51 victims, the Domodedovo International Airport bombing in which 89 people died, or the Beslan school attack with 335 dead, mostly children, also in 2004. Chechen asylum seekers have not been discriminated against even after the Boston Marathon bombing carried out by the Dzhokhar brothers in April 2013. This is because they were registered normally and the Chechen influx to Europe has not received the same level of attention as the current refugee crisis. In this way, Chechen refugees avoided the mixing of “migrants/refugee” and “terrorist” categories which has come to characterise the discourse of receiving European countries.

“A year is simply not enough”: The process of integration

Three years ago, the UNHCR published an article about the difficult situation faced by the refugees who had finished a year-long integration programme in Poland. “They lived in a refugee centre while their asylum applications were processed and during the year-long integration programme that followed. The problem came when the programme with its housing and living benefits ended and they were expected to support themselves. They have been homeless ever since”. According to Kalina Czwarnóg, a member of the Fundacja Ocalenie, the one-year integration is one of the most controversial parts of the Polish refugee system simply because of its short duration. During this time, refugees receive financial help, around a thousand złoty per month from the Polish state to live on. In the case of a family, the per capita amount decreases as per each additional person. With this money it is possible to live, but not in the bigger towns like Warsaw. Usually they try to find work where knowledge of Polish is not necessary, but this makes it harder for them to find time to learn the language and find a better-paid job. When the integration year ends, all state financial support is immediately cut, which makes it impossible for lot of people to pay the rent, food or in the case of families, buy books for their children. Those who are not able to support themselves may choose between two options: either go to the street or leave Poland and search for a better life somewhere in Western Europe. If the parents admit that they have no place to live, the state could take their children away. Those refugees who have no children can go to homeless shelters, but it is hard because of the language barrier. “For many years we have kept on telling the government that one single year is not enough. Maybe for people who speak Slavic languages, it would be possible to learn Polish in a year while having a job, but for people from Syria or African countries it is impossible, especially if they have kids”, says Ms. Czwarnóg, who highlighted another major problem related to pre-integration. “The system is not equal for everybody. Success depends on where you are living, which part of Poland. I think if we spend less money on integration, at the same time we have to pay more for social care, education, and so on. Children are not educated well enough, and, honestly, what can they do? Buy drugs and get marginalized.”

After the Polish Eurosceptic conservatives won a landslide victory in the national elections of last October, there seems to be little chance of improvement in the Polish refugee and immigration system. After the Paris terrorist attacks of last November, the new government hinted at the possibility that they would not take any more asylum seekers from the Middle East. The current crisis and the louder voices asking for the introduction of a “closed-door” policy in Europe could affect Chechens abroad. There seems to be an increase in discrimination against asylum seekers, especially after Paris and the New Year’s Eve incidents in Germany. So far, based on currently available data, there has been no change in the numbers of acceptances and rejection decisions in Poland regarding the treatment of asylum seekers from the Russian Federation. As of the end of August 2015, 14 people were granted refugee status while subsidiary protection and tolerated stay status was given to 74 and 79 applicants respectively, of a total number of 3131 applicants. But the situation could easily change.

Mamud is now working as a social worker for a Polish NGO helping asylum seekers from Chechnya and other countries. He has 8 more months until the end of the integration process. His plan for the future is to work for a bigger organisation like the UNHCR here in Poland or Brussels. Even though the Polish refugee and immigration system is far from perfect, according to him the Polish people have changed a lot during the past years. Mamud arrived alone in Poland two and a half years ago. His parents, brothers, and sisters are still living in their Chechen hometown. For years, his family have often been harassed by the authorities. Although recently they have not been harassed as much as before, they still want to leave Chechnya. But it is not easy. Even today, the current Chechen authorities create different obstacles aimed at preventing Mamud’s family and others from leaving. “On the other hand, I really want to go back, but only if the situation changes dramatically. Now it is impossible for me to return”. Just as it is for others.

Warm thanks to Elmira Ismailova for helping to interpret between Mamud and myself.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

Tensions in the Czech Republic Przemysław Witkowski reports from last Saturday’s anti-refugee demonstrations in Prague. Where did you get this information?