Toward the end of his adventurous, unhappy and brief life, an émigré Polish writer Marek Hłasko wrote that at the moment of his defection from post-Stalinist Poland in 1958 he did not yet realise that the world is divided into two halves, the life in one of them being unbearable, while that in the other was – intolerable.

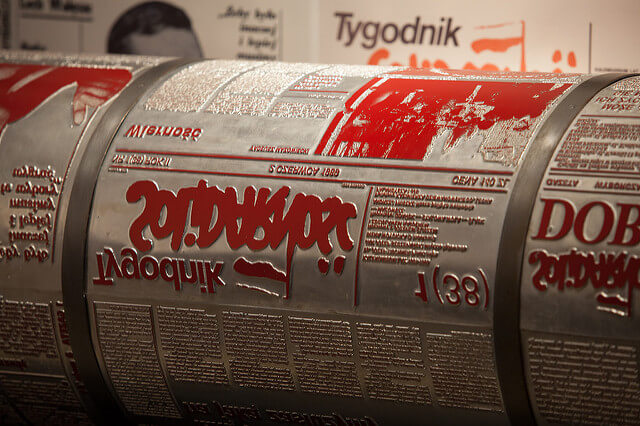

The Polish ‘Solidarity’ movement, which sprang to life in 1981 to shake the whole of Europe and precipitate the fall of really existing socialism, was animated by an idea that through abolishing an oppressive regime the life of the people in Poland, as well as in the other Central European countries, would become if not altogether happy, then at least bearable and tolerable. It may be appropriate to ask, thirty-five years after the birth of ‘Solidarity’ in August 1981, whether it succeeded in achieving its goals.

‘Solidarity’ from Edward Abramowski to Carl Schmitt

How should we assess the results of the peaceful transformation of Poland initiated by the emergence of the ‘Solidarity’ movement in 1981 and the first semi-democratic elections held in 1989, which brought victory to that movement?

The first ideological vision of the future Poland, adopted by the first Assembly of the ‘Solidarity’ Trade Union on October 7, 1981, was based on the idea of “the self-governing Republic”, inspired to some extent by the ideas of the Polish political philosopher Edward Abramowski, champion of anarcho-syndicalism. The “self-governance” advocated in this programme did not go so far as to demand the complete sovereignty of the Polish state. Having timorously assumed that Poland would have to remain within the sphere of influence of the still powerful Soviet Union, it proposed, in accordance with Abramowski’s idea of “state-rejecting socialism”, the construction of a socialist civil society which would be able to take care of itself without help from the state.

However, as soon as the activists of the Solidarity Trade Union found themselves swept to power in 1989, this idealist programme was tacitly abandoned.

Despite Adam Michnik’s personal admiration for Hannah Arendt’s political philosophy, which proposed a form of a non-liberal and non-representative “direct democracy”, her political ideas did not become the basis for the design of the future Poland, nor did Isaiah Berlin’s relativistic and agonistic liberalism.

An ideological framework for the political programme of the new sovereign Polish state was provided rather by Karl Popper’s idea of an open, civil and liberal society. At that time every Polish student knew the name of Karl Popper. His ideas, however, were soon reinterpreted in a conservative manner, just as Popper himself had gradually replaced his initial object of political admiration, the German socialist democrat Helmut Schmidt, with the conservative Christian democrat Helmut Kohl. Large sections of the Polish political and intellectual elite found Popperian liberal ideas all the more attractive as they were easily combined with the neoliberal ones of Milton Friedman and Friedrich August von Hayek. Fortified by Fukuyama-style propaganda regarding the finality and incontestability of liberal democracy, they set the political agenda for the social and economic transformation of Poland over the following decades.

Such an agenda was pursued not only by conservative liberals and other groupings emerging from the original mass movement of ‘Solidarity’, but also by the post-communist, nominally leftist social-democratic parties. Eager to free themselves from the burden of their inglorious past, they disregarded the egalitarian policies of the traditional left. In doing so, they gradually became alienated not only from their own nostalgic post-communist electorate, but also from what remained of the working classes. As a result, they have found themselves in a predicament in which their attempts to recover their old vigour and popular support seemed futile and misbegotten.

A striking example of the failure of an attempt to revive the Polish political left, initiated in the run-up to the general elections in 2007, may be attributed to the fact that a coalition of several leftist parties ignored the potential for political discontent of the Polish workers, organised, if only to a limited extent, by disunited trade union associations. It should come as no surprise that after the general elections of 2015 the once popular post-communist party Democratic Left Alliance found itself on the brink of total demise. To employ a term from Michel Houellebecq’s early novel, their disregard of the interests of the working classes boiled down to a failure to expand the political battlefield beyond the one delineated by the liberal agenda, to one that might stand for a more egalitarian political agenda.

I would argue that the chief reason for the current crisis of liberal democracy in Poland may be sought in a general tendency toward self-limitation of the Polish liberal and social democratic parties’ agendas. From the very beginning of the socio-political transformation of the country, Polish liberals deliberately confined their political interests to the economic sphere and worked to create an entrepreneurial class from scratch. Having created it, they subsequently exerted themselves to enhance its social and political role. At the same time, no less deliberately, they neglected egalitarian demands for the emancipation of wide social strata within the social, cultural and political spheres.

It is fair to say that this specific brand of liberalism, which played a hegemonic role in the Gramscian sense within Polish political discourse, both in its practical as well as doctrinal dimensions, is responsible for squandering the emancipatory potential of the ‘Solidarity’ movement, for generating a variety of political problems which stand in the way of the badly needed and much delayed modernisation of the country, and for contributing to the rise of authoritarian populism in Poland.

For the policies pursued by both the neoliberal section of the post-Solidarity elites, and the equally neoliberal post-communist elites, came at a price. As a result of this deliberate self-limitation of the political agenda, some important issues of the public life, abandoned both by liberals and post-communist social democrats, were picked up by radical, nationalist and fundamentalist political parties. In the general elections in 2005 these parties won significant popular support, claiming their first significant victory, and marginalising both liberal and social-democratic parties.

Psychopathologies of Polish politics

Emotions unavoidably play a crucial and indispensable role in the functioning of human societies. The dynamics of human subjectivity is of a fundamental importance in the sphere of knowledge, in moral conduct, artistic creation, as well as in the matters of politics. It is only natural that one of the chief tasks of a science of politics should be seen as an intelligent understanding of them, their adequate interpretation, and an innovative search for effective methods of their regulation and control.

Conceptions of political philosophy which disregard the sphere of human emotions cannot be adequate.

The psychological aspects of political life have constituted a subject of keen philosophical interest ever since ancient times. Insightful observations of the psychological phenomena which filled the political space established by the Athens’s democratic experiment were the basis for the political theories of the greatest Greek philosophers, Plato and Aristotle.

A deep appreciation of the political significance of human social emotions has played an equally fundamental role in the political works of Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith and John Locke. They were of the greatest import for David Hume, the leading thinker of the Enlightenment who in this, as well as in other matters, adopted a deeply sceptical attitude toward the Enlightenment belief in reason as capable of exerting its regulatory and controlling power over emotions. Hume famously argued that reason is and ought only to be a slave of the passions.

Athenian democracy opened the space for a more egalitarian expression of the political agency of human individuals for the first time in human history. The development of contemporary democracies, together with their accompanying technological and social advances, has resulted in opening up the public space for human individuality more widely than ever before. Since the sphere of human subjectivity is capable of more dynamic transformation than other aspects of social life, and since, within liberal democracies, human subjectivity and emotionality reveal themselves both to an unprecedented degree and in a diversity of novel forms, some of which tend to undermine social stability, they often come to be perceived as pathological. For this reason, an inquiry into political phenomena considered pathological has now become an independent and well-defined subject of scholarly interest.

It is often claimed that the presently dominant forms of Polish politics, and new developments within it, are a result of psychopathologies responsible for a gradual decline and degradation of the Polish politics as a whole. The degradation in question, it is argued, stems to a large extent from a failure of the Polish political elites adequately to understand and manage the emotions of Polish society. The failure has been a cumulative effect of various modes of political disregard, misuse and abuse of social emotions.

More specifically, as David Ost argued in his book The Defeat of “Solidarity”, this has been a failure resulting from the inability of one part of the Polish political elites to understand the role played by the “political emotional variable”, and, one may add, of the cynical instigation and exploitation of it in political struggles by another part. All these forms of misuse have together resulted in a manifest disregard of a common good.

Authoritarian populism

This degenerative trend in Polish politics may be attributed to pathological modes of employment of social emotions by some figures of the Polish post-‘Solidarity’ right, who through the manipulation of the popular emotions, have successfully dragged politics into the abyss of a new form of authoritarian populism. Jarosław Kaczyński, ambitious leader of the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice), has been particularly resourceful in this respect. Undeniably talented in orchestrating public emotions, he led his party to an electoral victory in the general elections in 2005.

This marked the beginning of a dramatic change in many respects of Polish public life. The atmosphere of the country under the rule of the Law and Justice Party, when one of the twin Kaczyński brothers (Jarosław) became Prime Minister of Poland and the other (Lech) served as President, has been adequately captured by Andrew Nagorski who wrote that the Poland of that time did not in the least resemble the country from 1989 when ‘Solidarity’ triumphed and not only toppled the communist government in Warsaw but set off a chain reaction throughout the region.

Commenting upon the situation in Poland in 2006 Nagorski wrote that “[d]espite enormous economic gains that have transformed the country from a land of chronic shortages into a bustling consumer society, despite Poland’s membership in NATO and the European Union, despite the banishment of fear and the emergence of a free society, many Poles are in a sour mood. It’s a mood that accounts for the recent emergence of a wobbly coalition government composed of right-wing populists, who are constantly bickering among themselves. What once was the ‘Solidarity’ camp is now split a half-dozen ways, and the air is filled with mutual recriminations about alleged collaboration under the old regime and corruption in the new era. In short, the romance of the revolution is largely forgotten”.

The reorientation of Polish politics effected by Jarosław Kaczyński cannot be attributed to his personal political skills alone. It resulted rather from an unabashed rejection of the thus far dominant liberal political rhetoric, entrenched amongst the elites, but not amongst the rest of the people. This involved bringing to the fore social issues, neglected by liberal and social democratic parties. But it also involved references to nationalist and patriotic ideologies. The reversal thus achieved affected the country not only internally, but also had important consequences for Polish foreign policy as a whole; especially the relations with Germany and Russia.

Polish foreign policy

The peaceful transformation of Poland initiated by the roundtable talks in 1989 was not only the symbol of an unprecedented change in the course of Poland’s recent history. It was also a turning point in the traditional Polish attitude to history itself. Roughly the first two decades of the transition from really existing socialism to democracy were dominated by the spirit of peaceful transformation. It seemed that history for the Poles would henceforth be changed not so much by desperate violent uprisings but rather through peaceful processes of negotiations and an effort toward mutual understanding with its neighbours.

Poland would be eager to learn, like other European countries did, to reconcile its newly regained national sovereignty with those of others within the European framework. During that time Polish foreign policy was almost unanimously understood as a way of promoting national interest through cooperation and agreement, and not through, often futile, even if justified, resistance or violence.

Post-war reconciliation between Poland and Germany was bringing its positive effects. For some time, it seemed certain that an old Polish saying which may be roughly translated: “As long as the world is the way it is, a German will never be a Pole’s brother”, would never be revivified to the rank of chief principle governing Poland’s relations with Germany. But this policy was abandoned by the Law and Justice government in the years 2005-2010.

Within a very brief period of time, Poland has found itself in the midst of a cold war with Germany and Russia, conducted by extreme nationalist and populist parties of the Polish right who profess a specific version of hostile winner-take-all politics. Polish foreign policy once again has become almost completely subsumed to the disastrous pre-war principle of ‘two enemies’, the enemies being Poland’s powerful neighbours, Russia and Germany. At the same time Poland has been searching for friendship, unreasonably and in vain, from a distant and increasingly aloof United States.

If one were to point out an ideological framework which would help to understand the politics of these Polish authoritarian tendencies, the most likely candidate would be the ideas of Carl Schmitt, an ideologue for the German Third Reich. The cultural repression of liberal and leftist ideals effected by the regime led by Jarosław and Lech Kaczynski, turned Poland, a country which suffered from the Nazi regime more than any other, into the place of an incomprehensible scandal, when if a crypto-Nazi assumed a prominent public position in Poland, this generated much less controversy than when a post-Communist did. No wonder that Polish young people nowadays have increasing difficulty in understanding why the liberal democracies of Great Britain and the United States formed an alliance against the German Nazi regime, rather than unite themselves with the Nazis against the Soviet empire of evil.

Fear of authoritarianism

But this period in Polish politics came to an abrupt end due to the tragic event which occurred on April 10, 2010, when a Polish governmental plane carrying president Lech Kaczynski with his wife and ninety-four members of the Polish political elite, crashed into a forest near Smolensk airport in Russia, killing everyone on board. The Polish delegation were to attend a ceremony that marked the seventieth anniversary of the massacre of some 22,000 Polish officers and intellectuals in Katyn forest near Smoleńsk by the Soviet secret police in April 1940. This traumatic event, which continues to divide Polish society until today, heralded the end of the radical and internally inconsistent coalition of right wing, nationalist parties, formed by Law and Justice in 2007.

Bronisław Komorowski of the Civic Platform, the Speaker of the Polish parliament Sejm, took over the presidential seat of the deceased Lech Kaczyński. As a result of the general elections held the following year, a neoliberal party, Civic Platform, won the majority. For eight years the Poles seemed to enjoy the predictability of this new government and its drive toward the modernisation of the country. Party officials were so far emboldened by the popular support they received for the leader to claim that his party had no one to lose the election to. In 2015, with the presidential elections approaching, Adam Michnik, in much the same arrogant mood, publicly claimed that the Civic Platform presidential candidate, Bronisław Komorowski, would lose the presidential election only if he had run over a pregnant nun on a zebra crossing while drunk driving.

He could not have been more wrong. Towards the end of its eight-year term, Civic Platform was in deep trouble due to quite plausible accusations of corruption of some of its ministers. Compromising conversations between Civic Platform’s members and businessmen secretly recorded and made public dealt it a bitter blow. The only remaining and incontestable strength of this neoliberal and conservative party seemed to be fear of the repetition of authoritarianism, consistently promised by the leaders of Law and Justice.

Despite these calculations and the self-assuredness of the liberal political elite, Civic Platform rule came to an unexpected end with the presidential and general elections held in 2015. In June little known Andrzej Duda, supported by Jarosław Kaczyński and Law and Justice, won the presidency against the incumbent Bronisław Komorowski. In October the same year Law and Justice swept to power, winning a majority sufficient to form a first post-transformational government without the need to enter any coalitions. The key to this astounding success was an ingeniously engineered campaign built, once again, upon corruption charges against Civic Platform, the appeal to nationalist and patriotic feelings, an ostentatious even if not quite genuine religiosity, and blatantly xenophobic innuendos formulated amidst a growing Syrian refugee problem.

The new government formed by the seemingly unelectable Law and Justice did not wait too long to confirm fears of authoritarianism. In no time the Parliament, dominated by the deputies of Law and Justice, had passed a new law concerning the functioning of the Constitutional Tribunal. The true aim of the new regulation was to make it difficult, if not altogether impossible, for the top court to overturn any parliamentary legislation.

This has been interpreted as a violation of the separation of powers and as opening the door for the authoritarian and unchecked rule of the party or rather its leader. Subsequently the government refused to recognize the court’s decision which deemed the new law unconstitutional. This has created an impasse for both sides of the disagreement, and generated both internal and international concern. Institutions of the European Union, as well as the US President Barack Obama, have rebuked Poland’s new government for violation of the rule of law, with little impact, however, on the ruling party officials.

A great vacuum

Despite the gravity of the situation, the largest opposition party Civic Platform has lost its steam and demonstrates an inability to present any persuasive alternative, while its leaders have become engaged in mutual recrimination. This has left a great vacuum on the opposite side of the profoundly refurbished Polish political spectrum. Some of the former Civic Platform electorate is now represented by a new party Nowoczesna.pl (Modern.pl), led by a former pupil of Leszek Balcerowicz. The concern about the rule of law has been exploited more successfully, with the help of social media, by a Committee for the Defense of Democracy (Komitet Obrony Demokracji, KOD; it’s name deliberately refers to Komitet Obrony Robotników, KOR, the key Polish opposition movement against communism). Even though KOD has managed to stage several great demonstrations against the new regime in major Polish cities, it has not yet turned itself into a political party.

The vacuum on the left side of the political scene is now being gradually filled by a sensible and energetic young party ‘Razem’ (‘Together’) which has secured for itself 3 per cent of the voters. All these political fractions, however, are being systematically undermined in their opposition against the Law and Justice. A reform package undertaken by this party on behalf of the underprivileged segments of the Polish society, is meanwhile being rewarded by growing popular support.

The question frequently asked is why the Poles have chosen, again, Law and Justice, a party which does not have any qualms whatsoever in appealing to nationalist and xenophobic ideology, as their political representation. Many commentators, like Nagorski quoted above, point to the enormous gains Poland has achieved thanks to its wholesale transformation.

The transformation initiated in 1989 has brought to Poles a tremendous change: they now live much more dignified and prosperous lives than they did under a communist regime. One has to add that Poland indeed fared quite well through the post-2008 economic downturn.

The country has been consistently presented by political propaganda as a “green island” of growth amid the shrinking economies of the European Union. However, even if all this is largely true, there are several things to be borne in mind.

First of all, what has been rarely mentioned during these transformative decades was that the wealth produced by Poles has been unequally distributed among them. This economic growth should rather be seen as an indicator of the level of poverty from which this country was trying to emerge, rather than as a sign of its economic strength. Secondly, this growth has been achieved at the cost of the low wages of Polish workers.

Moreover, 8.6 per cent of the workforce in Poland are presently out of jobs, with few of them eligible for state support. Poland is among the most unequal societies, with the value of the Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income at 30.08, rather distant from the prosperous egalitarian countries. Yet another indicator is much more telling:out of 23.5 million Europeans living off an income of less than 10 euros per day, 10.5 million, i.e. nearly a half of them, are Polish citizens. The authors of the statistical European Union survey of 2008 state that “[l]ooking at those with the lowest incomes [i.e. below €5 a day], we find that 44% of them live in Poland”. With subsidies for research and innovation at a consistently low level, the Polish economy continues to be rather outdated and European Union handouts are the only reliable source of cash helping to modernize this backward country.

Poles suffer also from a number of other iniquities and exclusions. Women, who are denied equal access to jobs and equal pay, are also the first to be fired from their jobs. Under the pressure of the politically dominant Catholic Church, they are denied a right to abortion; and the allegedly liberal Civic Platform, under the pressure of the Catholic Church, also considered a ban on in vitro fertilization, even if the state (once again because of the unyielding stance of the Church) had not been financing this.

Civic Platform had also been planning to castrate pedophiles, while appealing, in the same breath, for mercy for Roman Polanski who some time ago was jailed for sexual intercourse with a minor. Sexual minorities are repressed, critical and innovative artists are censored, while the state turns its gaze the other way. Public access to arts and cultural events is marred by economic exclusion and psychological attitudes of self-exclusion: less than ten per cent of Poles take part in cultural events on a regular basis.

Polish society is also coping with the grave consequences of four structural reforms which were intended as a Polish version of the Great Leap Forward. The four reforms, effected by the liberal conservative government in the years 1997-2001, turned out to be disappointing four steps backwards. After a decade, the pension system, reformed along the lines of neoliberal principles, has crumbled, leaving a large hole in the state budget and the future if pensioners deeply impoverished.

A decade after the reform of the health system, medical services were diagnosed as very inadequate and are steadily deteriorating. The administrative reform – an attempt to introduce the idea of self-governing Poland in practice – has only multiplied the army of bureaucrats at all levels. A reform of the educational system produces now hordes of semiliterate philistines, as do the higher education institutions. Cultural institutions, courts of justice, the police and other public services, are inadequate due to their underfunding.

This, ironically, may be read as a proof of the statement once made by a leading member of the Civic Platform government who has been recorded as saying that the Polish state exists only theoretically.

One world, vanquished hope

Some two million Poles took the opportunity afforded to them by the accession to the European Union to improve their lives by emigrating to other European countries, especially Great Britain and Ireland, but also Germany; a majority of them do menial jobs.

This is the largest emigration in the Polish history.

Unsurprisingly, it generates a strong backlash among host societies. This has been so especially in Great Britain, where the overwhelming Polish presence was a strong card in the successful Brexit campaign. The number of Polish emigres itself should be interpreted as an another telling indicator of the quality of life in present-day Poland. In view of the great number of Poles who found themselves in a situation desperate enough to emigrate, one may be permitted to speculate that a much larger army of them might be ready to follow suit. Indeed: the 2016 survey suggested that another 4 million Poles are willing to leave their country, while 1.5 million are ready to do so.

It is for such reasons that the year of celebrations of the 35th anniversary of the commencement of the liberal and democratic transformation of Poland is not universally felt as a moment of contentment or as an occasion for self-congratulation.

**

The article was originally published in openDemocracy.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)