2018 will see the premiere of Solidarity in Europe, a documentary directed by the Italian filmmaker Berardo Carboni and produced by European Alternatives as part of a Horizon 2020 research project into transnational solidarity in times of crisis. The film will show a journey across Europe, collecting instances of transnational actions and citizens mobilisations in dozens of cities, featuring key speakers from different backgrounds, including Gesine Schwan, Yanis Varoufakis, Ken Loach, and Inna Shevchenko. Henryk Wujec, a Polish politician and historical member of the Polish labour union Solidarność, met the filming crew and researchers to give his point of view on the future of a country that he helped to construct in the 80s, and that will determine Europe’s future in the coming years.

Marta Cillero: Last November Warsaw experienced the darkest moment it has seen in a long time: thousands of nationalists and fascists marched through the city to mark Poland’s independence day, carrying banners with such slogans as ‘White Europe of brotherly nations’, ‘White Europe’, ‘Clean Blood’. How do you understand these mobilisations?

Henryk Wujec: The whole thing left me shaken. But this is not something that emerged suddenly. We’ve had these sort of signs during earlier rallies held by these organizations. Obviously I oppose it with all my heart, I don’t like it one bit. This is the complete opposite of the idea of Solidarity. It’s like heaven and hell. Solidarity was a mass movement too, but it expressed emotions differently and had a different approach to strangers.

Obviously I oppose it with all my heart, I don’t like it one bit.

This is something completely different. I do think about it, but it’s hard for me to analyse. It’s not a simple process, it doesn’t happen suddenly, and it is serious. Similar processes are now taking place in many European countries. Poland’s case is drastic, but for example Hungary went through the exact same thing, perhaps even more intensely. Similar things are happening in France – we could see that in the recent electoral campaign – and in Great Britain during the Brexit campaign. Spain experienced something similar. This wave of nationalism is sweeping across Europe.

I’ve lived long enough to become interested in the long-term changes in historical events and I can draw analogies between the situation today and what has been happening in Europe in the 30’s. The pre-war situation in Poland, Italy, Germany and so on, resembles what is happening now greatly. Again we have masses fascinated by nationalist slogans, infatuated with great leaders and marching towards horrible consequences. We know this, but perhaps some young people do not see that what they participate in can lead to catastrophe. I believe it is our task to try and stop it, to make them understand the possible consequences.

To counter these marches we have demonstrations held by anti fascist groups and by the old Solidarity movement as well. These initiatives are full of empathy and friendliness, so there is a potential for something different. Many institutions actively oppose these nationalist tendencies. I personally am a member of the International Auschwitz council. It is an important institution managing the Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial and many other death camp sites in Poland – and there were many camps located in Poland. This council had a meeting recently and issued a warning statement about the threat of fascism in Poland. There is a potential to oppose fascism, but the government is permissive in the face of extreme right wing groups and would rather imprison a group of women who attempt to oppose this march than actually obstruct a theoretically legal fascist march. The government tolerates this movement for political reasons – it gains them popularity.

The pre-war situation in Poland resembles what is happening now greatly.

Speaking of solidarity, it is remarkable that the fascist rally in Poland was also attended by representatives from other countries, from Hungary or Croatia for example. There is some sort of communication between them. But it also means that if we want to fight them, and we need to fight them, if we don’t want to be responsible for a catastrophe which is bound to happen, we also need to search for allies across borders. We’ve the right to express our opinions, we’ve the right to communicate with others and to express our values, especially given they are European and humanitarian.

I think this is the dawn of a new movement. They have it easier as they get organized given they are probably supported directly or indirectly by Putin’s Russia. They do have money. But we also need to get to work to stop it. It won’t be easy and those who try will be persecuted, will suffer as they volunteer to do so, but I think it is impossible to obtain anything without a little risk.

Since 1989 Poland has implemented neoliberal political and economic ‘solutions’, based more on individualism than social solidarity. Why do you think this was the case? What is behind the shift to the right in one of Europe’s most important countries, a country that will determine Europe’s direction in the coming years?

Forty years of real socialism has branded us. We experienced the system on a daily basis, at school and at home, in the shops and on the street. We were soaked in it and we could live in these times but it was awful and hideous. When the system was finally toppled and collapsed – which was a miracle – we didn’t plan it! We treated every mention of it returning like a threat. In that system everything had to be collective, had to be centralised. One couldn’t do anything out of his or her own initiative. I worked in a factory, a modern factory operating modern machinery. Even there, whatever we wanted to do, the party’s secretary – who was not an engineer – had to decide whether or not we could. It was degrading to everyone who considered themselves subjects with free will and the ability to cooperate.

When the system was finally toppled and collapsed – which was a miracle – we didn’t plan it!

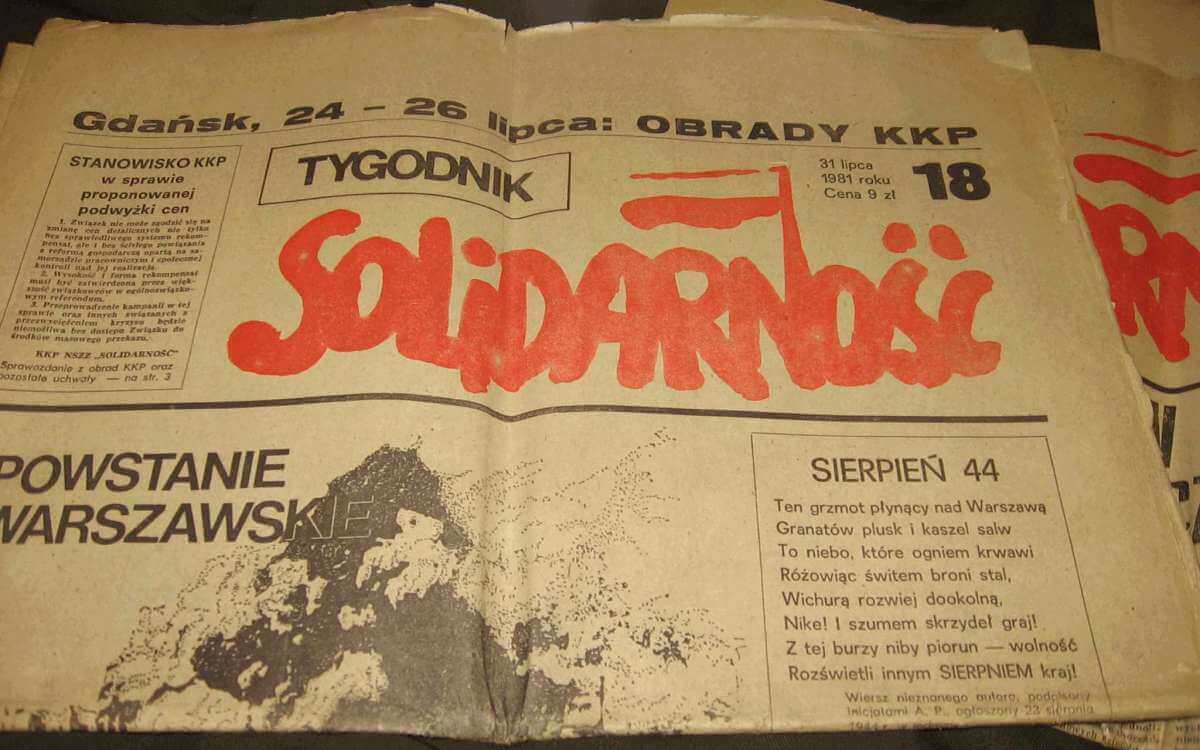

Solidarity had its own ideology, its positions formulated during the first congress in 1981. This was an essential event, basically the first free and independent parliament in post-war Poland. The programme stated that Poland was to be ‘grass-rooted’: created and run “from below.” It might even have succeeded, but of course general Jaruzelski had a different idea, so he banged most of us up. The idea, though, remained very much alive. So when we were finally able to implant some of the changes we felt were needed, in 1989, there was an intention to return to these ideas and experience, to actually make use of them. But the idea of creating autonomous and self-governing ventures was no longer popular. People didn’t want that. There was one economic system we knew worked around the world, that of private enterprise. We didn’t have to estimate its chances of succeeding, we only had to look out the window and compare the view with that in, for example, Sweden.

In 1956, when I was a high school graduate, Polish government became temporarily more liberal. Gomułka said we could show the world that real socialism was a brilliant, effective system by implementing it in Poland as it was implemented in Spain. Back then they were on a similar developmental level. It was a sort of a competition – let’s see who will be better off in 20 years. And see that we did. Poland was still a sad dunghole and Spain kept flourishing. Experience showed us this system was ailing and deficient, and to make things worse it humiliated people. It had to be changed. And the only alternative that had actually proved itself effective was that of liberal economy. Changing that system wasn’t easy either! We were falling head first into an economic catastrophe, we couldn’t just experiment on a whim.

No one, no outstanding specialist or economist would take up the task of pulling our economy out of this malaise. Only one decided he could and would do it – Leszek Balcerowicz – a young economist from SGPiS (a former school of economy in Warsaw, now SGH). He was a member of Solidarity so we knew him, and he had the courage to try. But he was an abject adherent of the liberal model and that’s what he gave us. To make things worse, this system did work for some time! We were infatuated by the new possibilities. If you walked through the centre of Warsaw back then, you would keep tripping over cots and camper beds which people dragged into the streets and covered with goods for sale. Everyone had something to sell and wanted to sell it, because they needed money, but mostly just because now they could!

We were infatuated by the new possibilities.

Poland started to develop, but at a cost. And we didn’t know the cost would be so severe! Everyone thought it was just a necessarily rough transition period. As a result we now have the very basis of solidarity – the big factories and state-owned enterprises which employed thousands of people – shutting down. All because they do not fulfil the standards of the market. What was modern for us in the socialist period turned out to be archaic and useless when we realised we were 20 years behind Western industry. No one would buy from us, so the industry started to crumble. People lost their jobs. What followed were thousands of tragedies and lots of suffering. Some managed to find their place in the new system, but many had their lives destroyed by this situation. It’s horrible. Poland did go up in terms of economic development, it’s actually one of the highest in Europe, so we should be happy. But we are not. People want and need something more. And perhaps that lies at the core, maybe that is what we should try and analyse.

What is solidarity? Is it something different to transnational solidarity? Can Europe survive based far from solidarity values?

This time let me start with the last issue you mentioned. Poland’s prime minister and the ruling party’s leader stated they wouldn’t let a single refugee into the country, because they fear terrorism and diseases – those were the only reasons mentioned, so ones based on spreading fear. That attitude goes against everything solidarity stood for. It violates the constitution, Christian values which are sacred to many people in Poland, and even against our national traditions. This government follows a course of anti-solidarity. It is shocking, also for many ordinary people. Granted, many citizens agree with the government, they are glad to be safe from these attacks they were warned against and are constantly threatened with.

But it is not possible to live a life focused only on egoism and one’s own comfort! That’s not what we live for, it is our humane duty to care for others. Luckily there are still people and institutions who oppose this hostility. Surprisingly, the Catholic church in Poland opposes the government’s stance, mainly because Pope Francis is very open, very sympathetic towards refugees and their cause, and it was he among others who proposed to open humanitarian corridors through Europe which would allow for the transportation of those in greatest need who could then be hosted by European countries. And even that idea was rejected by our government, despite the fact that the church was ready to create them and host refugees in their parishes.

But it is not possible to live a life focused only on egoism and one’s own comfort!

Becoming a part of the EU was a huge accomplishment, we were proud of it. Now there are also many critical, even hostile voices against the union. Even the prime minister seems to be hostile towards it. When the European Parliament published a resolution decrying the damages to the Polish judiciary, Beata Szydło, the Deputy Prime Minister, said she felt offended, and that Poland was offended. Well, if you are a member of a community and everyone in the community tells you you’re doing something wrong you can’t just pout and say you feel offended, you need to stop and think what you’ve done wrong! That kind of behaviour is unacceptable! And of course it worries me. At some point even Kaczyński mentioned that their position of power is more important to them than keeping Poland within the EU. We are facing a threat of being ripped out of this community, but it’s not that easy. Still they try to marginalise our role in the EU. Perhaps they don’t intend to, but that’s what they’re achieving with their policies.

I’m still an optimist though. Poland is not an easy country to rule and I think PiS will fail in governing it as well. There will always be movements opposing the government who will not keep quiet. But it cannot be done individually. We need a community to work against these tendencies, against the populist and nationalist tendencies we’re facing. And as we look into their core, into the reasons their members have to follow them, we might actually find a remedy for their spread. Those people are heading towards a blind corner but we can’t just shout this fact at them. We need to find a common language.

Some recent surveys have shown that a majority of those in Denmark, France, Germany, Italy and Poland would vote to stay in the EU if a referendum were to be held. Why do you think this is the case in Poland?

I actually think Poland has the highest support for EU membership among all the member countries. It stems from our history. For ages we’ve lived in a hopeless system. We were locked in a camp – I think it’s an appropriate name for the communist country. If someone actually managed to get out, the difference was astounding. And you didn’t even have to go to a capitalist country. For example we’d go to Hungary which was more liberal and was even called a socialist showcase. It was enough to go there to see what freedom was in a capitalist sense – you could buy whatever you wanted, unlike in Poland. So even these few occasions were precious. When Edward Gierek was the first secretary (The Polish United Workers’ Party leader) we could go abroad every now and then, and we’d always see that Poland was an undeveloped, quaint country and that the reason for this was socialism.

The EU has large support because people have experienced what it means to be a member country. People may complain, but they have the freedom of choice. If there’s no work here, they can go somewhere else. They are not condemned to fluctuations of the labour market here. We’ve been a member since 2004 and during the referendum the support wasn’t so staggering, in fact I think it was just over 50%.

People may complain, but they have the freedom of choice.

The people who are now expressing their discontent by participating in these marches we talked about were also against the EU back then, claiming that Poland would lose its spirituality and that we’d have atheists destroying our religion and faith, that they would flood us with cheap produce that would impair Polish industry. Actually the opposite happened. It was the Germans who came shopping to Poland: our market is cheaper, the food is better quality and tastier. They came to buy, they paid and they were ready to pay a lot. And not only Germans. Poland became attractive to people from Ukraine, from Belarus and so on.

And yet this positive change that we are developing wasn’t accompanied by a sense of security for the individual. When I worked in a factory back in socialist Poland, I knew I would always work in the factory, unless I was politically active, in which case I could get laid off. But now it’s different, today you’re employed, but you don’t know what will happen tomorrow. It’s nerve wracking, people are uncertain about their future and perhaps that’s the reason for the discontent. You always have to be on the lookout. In my factory I didn’t even have to do much. Arrive, punch in, punch out, leave. Today I’d always have to worry about being discarded.

For me, though, the most important thing is that the European Union fulfilled many of our aspirations, and for this reason we will not reject it. Law and Justice knows that they cannot threaten our membership because it would cost them dearly. Unless they conduct a prolonged campaign slowly sowing doubt and hostility against the EU – that it brings chaos and malevolent ideologies – perhaps then, together with some church officials they can demand that Poland rejects this ‘devil’ and remains poor but proud and sovereign. That could potentially happen, but not now. I don’t think this is a moment for shutting Poland off. The world is more and more open, we can travel, we have access to the web and even if public TV is feeding us lies we don’t have to rely solely on it. There are other media, other sources of information. I think we can defend our membership of the EU.

Law and Justice knows that they cannot threaten our membership because it would cost them dearly.

I’m proud to live in a European country. Europe is a small continent, but it’s a continent which has changed the world radically. Its thousand years of history show that as long as you give people the possibility to develop, express and create, he or she can create great things – like scientific development. Our lifestyle is important to us, it is the basis for democracy which took time to grow but exists and is the only reliable concept of peaceful, prolonged autonomy and self-governance. This experience is also visible through the history of the EU. Thanks to it the status quo can remain intact even in times of crisis, such as we’ve seen in Greece. It means an active role faced with change and difficulties, it means empathy and the obligation to help others. I envy Angela Merkel that she was open enough to bring in the refugees. Our leaders cowered behind all that aid they get from EU without being willing to pass it on. That’s how they pushed us out of the main current of events in Europe. Europe mustered up a gesture of hospitality and kindness, and this is actually something traditional.

You might say I’m very Polish in talking like this. I come from the countryside, my father was a simple farmer – and I got to know the traditional Polish country and I like and respect it, together with the Christian tradition in songs and literature. But I also see Poland as an important part of the European mechanism and I know that searching for answers is necessary. As a former opposition activist I know we can’t just hope for someone to come and do this for us. That won’t change a thing, only getting up and acting up can work. There are people ready to fight for our European membership in this huge community. I’m old now, but I believe I can still help a bit too.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

A good interview, but it neglects to mention the impotence of the opposition in Poland, where the social democratic left has had an even more precipitous decline than in many other countries. The neoliberal transformation from communism in Poland coincided with globalisation. Poland’s economic position depends very much on a well-educated monocultural workforce which gets one third the income of workers in Western Europe and North America. The Solidarity union of today is a sick shadow of the original, and is mainly an appendage of Law and Justice, while the more independent union movement descended from the Communist-dominated one is not particularly militant. Since this article was written, the parliamentary opposition has demonstrated its total incompetence in not supporting Barbara Nowacka’s “Let’s Save Women” citizens’ initiative bill. One can only hope that something like New Zealand’s political miracle of the last few months can happen in Poland, and that despite the dismal polls a young leader (such as Barbara Nowacka) can bring a renewed left to power. Kaczynski has a self-destructive record of generating division and chaos, so I don’t believe in the inevitability of the far Right.