No matter how disappointing or alarming the election results in Slovakia are, make no mistake, they cannot be treated as a real surprise. There are very few parallels, if any, between the rise of Marine Le Pen, UKIP and AfD in Western Europe and the rise of far-right extremists in Slovakia. The root causes of the election outcomes are logical results of local trends, some of them long-term, underlying the political scene since the division of Czechoslovakia.

The “threat of immigration” seems to have played a minor role in voters’ decision-making. No matter how good a populist you are and how much fear you can instigate initially, if the perceived threat does not materialize for a long time, the audience will not only stop fearing, but lose trust in you as a story-teller.

First and foremost, it is important to keep in mind that it was the Smer-SD party that won the elections for the fourth time in a row. No other party even comes close to such a colossal political presence, which is even more impressive when considering that since 2012, they have held power alone. Smer-SD is a nominally social democratic party and a member of PES, in reality more centrist and in many aspects closer to Chancellor Merkel’s CDU than SPD. The party that came second, the neo-liberal, pro-business, laissez-faire, LGBT-friendly though xenophobic and Eurosceptic SaS got less than half the amount of Smer-SD votes, although two months before the elections it was still unclear whether they would cross the 5% threshold to remain in Parliament.

Winner or loser?

Secondly, unforgivable and scandalous as it was, the Prime Minister’s Islamophobic rhetoric does not seem to have had much influence on the gains of right-wing extremists, and this is supported by exit-poll and post-poll socio-demographic data. The “threat of immigration” seems to have played a minor role in voters’ decision-making. The lesson is that no matter how good a populist you are and how much fear you can instigate initially, if the perceived threat does not materialize for a long time, the audience will not only stop fearing, but lose trust in you as a story-teller. The legendary master of suspense Alfred Hitchcock might have had a word or two of advice for Robert Fico’s campaign managers.

People ceased to be scared and they started to care about the reality of their daily lives again. Where there is the “invisible refugee” on one hand and the very real teachers’ and nurses’ strike on the other, the reality of which is driven home by the visibly struggling medical and educational system, it is not hard to guess which concern will take precedence. The biggest mistake Robert Fico seems to have made in his campaign was to ignore these people and treat their grievances as nonsensical. The 16% loss in comparison with 2012’s results, which was a lot more than anyone predicted, most probably occurred due to a botched campaign. It was national stability that the second Fico government brought, in stark contrast to the disorganized ensemble of right-wing coalitions, and which was highly valued among Slovak voters. This aspect of the campaign was communicated too little and too late, by a visibly exhausted prime minister in a defensive position, and only once the polls started showing rapidly waning support four weeks before the elections.

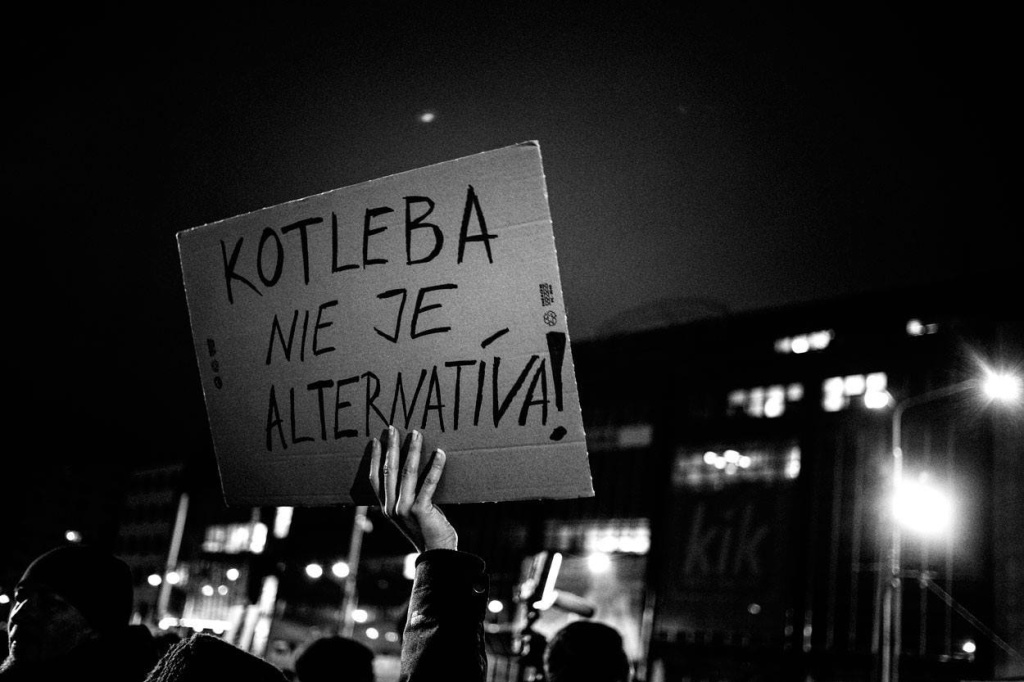

Coming back to surprises: it was assumed by many analysts that the neo-Nazi party Kotleba-LSNS would come close to the 5% threshold, although in pre-election polls they were fluctuating between 1-3%, because of the “hidden voter” phenomenon. This is a particularly nasty aspect of Slovak politics with its roots deep in the 1990s, when the supporters of the authoritarian and anti-western Vladimir Mečiar would not admit they voted for him. Such a vote was generally unacceptable in polite society and everyone supporting his party was considered a moron by the intellectual elites and the media. Therefore, the real surprise here is the large margin above the threshold: 8% in a relatively high turnout is frightening, 210 000 voters in pure numbers. It is important to understand that these are not nationalists like the Slovak National Party SNS. Kotleba-LSNS is a real neo-Nazi party. They consider themselves, and in fact they are, followers of the so-called Slovak state that existed during Second World War. In reality, this was Hitler’s puppet regime which willingly sent at least 60,000 of its citizens to their deaths, as Slovakia was the only non-occupied country that voluntarily took part in the Holocaust. The party legally exists due to a loophole in Slovak law which does not prohibit celebrations of the Slovak war state.

It is also worth mentioning that this party was not publicly visible. It had no significant media backing or a big campaign, in contrast with all other parties, even those deep below the 5% threshold. Therefore, with a great feeling of unease, we have to admit to ourselves that their voters decided truly freely.

Has discourse shifted voters to right-wing extremists?

The trend of radicalization and rising support for extremist parties has been developing gradually over a longer period of time, at least since the 2012 elections. These elections were completely overshadowed by the biggest (so-called ‘Gorilla’) protests in the history of Slovakia, taking into account that the 1989 revolution was a Czechoslovak, not a Slovak, moment. The publication of leaked secret service files proving beyond reasonable doubt corruption of monstrous dimensions among all the mainstream parties (except Smer-SD, which was not directly involved in the dealings described) triggered a wave of protests. Smer-SD took the elections in a landslide victory, but did nothing about the issues that brought people to protest all over the country in the freezing cold of February 2012. Adding insult to injury, some high ranking Smer politicians, such as the chairman of Parliament, were found to be involved in similar shady dealings of their own (the chairman resigned as a consequence). The logic of many people who ended up voting Kotleba-LSNS was therefore very simple, if flawed: when all the mainstream parties are so thoroughly corrupt, let’s look outside the mainstream. Unfortunately, there is no leftist party to speak of, nor a strong green movement; the only “alternative” is the neo-Nazis.

The election results must be seen through the prism of last-minute decision-making, where many voted out of anger over social affairs; they cast their votes in protest and as a “punishment” to mainstream parties.

This outcome was heralded by the neo-Nazi party leader Kotleba’s election as regional governor of Banska Bystrica in central Slovakia two years ago, a long time before any talk about refugees. There are no immigrants, no Muslims or other minorities in the region, but unemployment and other social problems abound. At the time, the reaction of the mainstream parties and also of most NGOs and the media to this early warning was a resolute “more-of-the-same” attitude, implicitly supporting the mainstream parties at all costs. Kotleba-LSNS had significant support among the so-called alternative media (online radio, Youtube, blogs), which caught the attention of young voters, who use the internet as their primary source of information. A third of Kotleba’s voters, however, were people who did not vote in the last elections, nor probably in those before, given that participation has been in steady decline since 1998.

Who is Kotleba and is he alone?

The party is full of Holocaust deniers and Hitler fans who have repeatedly been in conflict with the law for attacking foreigners, Roma and LGBT people. It is highly improbable that they would become part of any coalition and, as in Slovakia the opposition is generally sidelined by the ruling coalition, they will wield no real power. The problem is that Parliament will provide a very good stage for their propaganda performances, which is an especially worrying fact considering that MPs have full immunity for their statements. Another matter of concern is what will happen outside of Parliament, in the streets. It is very probable that attacks on anti-fascists, foreigners and minorities will rise as the fans and voters of this party feel emboldened by the election results. Let’s hope the police, judiciary system, the other parties and the media will treat this situation for what it is and not as an excuse to score points for themselves. Scepticism, based on experience, prevails.

Nevertheless, let us not forget about yet another “anti-system” party: Boris Kollar – Sme rodina (Boris Kollar – We are family), which got into parliament with almost as many votes as Kotleba. The leader, whose name the party bears, has 9 children with 8 different women and is a former middle management mobster (shortly after the election, police files documenting his involvement in large-scale drug trafficking surfaced); although he never wore a Nazi uniform and probably knows very little about the wartime history of our country, his opinions are similar to Kotleba’s. He is fiercely xenophobic, Islamophobic, anti-EU and pro-Putin. The so-called alternative media “created” and supported him no less than they supported Kotleba, so his voters are coming to a large extent from the same “source”. Although the leaders of these parties with no internal democratic structure would deny it today, they are natural allies, and let us hope we do not see the day when they realize it.

Some good news

There were some positive outcomes after all. Firstly, after almost two centuries, the Slovak trauma of Hungarians seems to have been brought to an end, at least on the political level. The Slovak national party SNS has no problem working with the main Hungarian minority party Most-Hid (“Bridge”). The fundamentalist Christian democratic movement KDH – with its own blend of sympathy for the wartime fascist regime and strong ties to the local Catholic church – is out of parliament for the first time since the 1989 revolution. Moreover, it seems their voters didn’t migrate to Kotleba, according to the available data. #Siet (#Net, hashtag included), a new pro-business neo-conservative party, fell dramatically short of expectations and barely crossed the mandatory threshold, despite a huge and expensive advertisement campaign running long before the elections. It was embroiled in accusations over unknown sources of financing and has a leader with limited appeal. The party itself is already falling apart, with three MPs left just a week after the elections, and it is almost certain that the party will never return to Parliament again.

What is this party? Where did its money come from? Given the very large funds available for its day-to-day existence and campaign that its leader was unable to declare the origins of, (a not unfounded) rumour has it that the party was an attempt to create a new leading party out of the ashes of the decomposed right. The party was meticulously planned as a pet project for the business interests of one of the richest and most corrupt local oligarchs. Why did this plan fail? For the same reason Smer-SD lost so many votes, and why so many ordinary people voted for the neo-Nazis. An important part of the electorate decided whom to vote for only in the final weeks before the elections, or even on Election Day itself. Had Fico been more “social democratic”, had he shown some emotion towards the people struggling to provide for their families, including those on strike, instead of pretending that everything works just fine except for the “Muslim threat”, the party would have scored higher. The election results must be seen through the prism of last-minute decision-making, where many voted out of anger over social affairs; they cast their votes in protest and as a “punishment” to mainstream parties.

It therefore seems that the time is ripe for leftist ideas to take root in Slovak society, chronically resentful of anything connected to the former communist regime. To put it bluntly, when you have people willing to vote for open neo-Nazis, is it really likely the right-wing establishment could discourage people from voting for the left by invoking the mantra of the “red scare”?

Photo by Peter Leto Škodáček.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)