On International Women’s Day in early March, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) published a report stating there is an “urgent need” to increase HIV treatment and prevention for women and girls around the world. “Girls and women are still bearing the brunt of the AIDS epidemic,” Michel Sidibé, the Executive Director of UNAIDS, laments in the report’s introduction, pointing to stigma, discrimination and violence as factors that make women more vulnerable to HIV than men.

None of this is news to Svitlana Moroz, who heads up Positive Women, a Ukrainian NGO that advocates for the rights of women living with HIV across the country. Last month, Moroz and other activists filed a report to the UN, alleging violations of human rights of HIV-positive women in Ukraine.

Other women have been accused of being drug addicts, denied health care and had their children take from them — all because of their HIV-positive status.

Moroz and other activists have collected disturbing stories from women with HIV across Ukraine. Natalia, a pregnant HIV-positive woman in western Ukraine, was turned away from a maternity ward, being told there was no place for “people like her”. Another pregnant HIV-positive woman managed to get into the hospital, but was placed in a room with broken windows in winter — she was told they couldn’t put her with other women. Other women have been accused of being drug addicts, denied health care and had their children take from them — all because of their HIV-positive status.

Some women have lost even more. Vera, an HIV-positive sex worker, gave birth by caesarean section in hospital. When she awoke to ask the doctor, a woman, how the surgery had gone, the doctor replied by saying she’d performed a tubal ligation without Vera’s consent: “You have no right to build a family and have children.”

Vera, unfortunately, isn’t alone. She is one of many HIV-positive women in Ukraine who have had to deal with institutional discrimination.

HIV back on the upswing in Ukraine

Prior to 2014, Ukraine was putting up a strong fight against one of the worst HIV epidemics in Europe. Thanks to concerted efforts from government, civil society and international donors to provide treatment and prevention programmes to at-risk populations, by 2012 Ukraine had actually reported a decline in new HIV cases for the first time. It looked as though the country was about to turn a corner.

That’s all changed, following the outbreak of conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014 and the country’s turbulent political and economic situation. Ukraine’s Ministry of Health estimates that at the beginning of 2016 there were 220,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in Ukraine — a prevalence rate of 0.9%, with almost equal numbers of men and women testing positive.

The trends over the last year are worrying. According to the most recent statistics from Ukraine’s Public Health Center, part of Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, the number of new officially registered people with HIV/AIDS rose by almost eight percent in 2016; most (62%) of new infections came from sexual intercourse, while 22% from intravenous drug use. While deaths from HIV-related causes have been on a decline worldwide, the mortality rate from HIV-related causes increased in Ukraine by seven percent in 2016 – the majority (52%) caused by tuberculosis.

These official Ukrainian government statistics don’t include Crimea or the parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts not controlled by Ukraine (the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic”). This means these figures could actually be an underestimate, especially since Donetsk, says UNAIDS Ukraine country director Jacek Tymszko, has long been an epicentre of Ukraine’s HIV epidemic. More than half of all officially registered Ukrainians living with HIV live in Odessa, Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk oblasts as well as in Kyiv.

Stigma “is still very strong”

Ilona, a social worker in Kyiv who works with people who have HIV/AIDS, knows how tough it is to be a woman living with HIV in Ukraine — she tested positive herself for HIV ten years ago.

Ilona tells me about a time when, before she’d disclosed her status to many people, she and her husband had a group of friends over, including her mother-in-law. Some of these friends, Ilona says, were HIV-positive, and her mother-in-law (“a good, accepting person,” she made pains to stress to me) knew about the HIV status of some of these friends and had no problem with it.

“But when they left,” she tells me, “my mother-in-law asked me to help disinfect everything they touched,” all despite the fact HIV can’t be spread by touching shared objects like toilets or cutlery. With her mother-in-law at that time unaware of her HIV-positive status, Ilona helped her disinfect and scrub everything her HIV-positive friends had laid a hand on.

She’s able to laugh about it now, but it still hurt. “It was quite humiliating for me,” Ilona says.

That said, there has been some progress in reducing stigma against people with HIV in Ukraine. A Democratic Initiatives poll from 2016 showed that 21% of people surveyed believed that people living with AIDS should be isolated from society, down from 36% in 2006 and 50% in 1991. “It’s moving in the right direction,” says Dmytro Sherembey from the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living With HIV/AIDS, “but it’s still very strong.”

Aside from her own experiences, Ilona’s worked with women of all ages and backgrounds who’ve tested positive for HIV. She’s seen how women of all backgrounds — particularly older women, she says — have a difficult time accepting their diagnosis. “They see [HIV] as a disease for those at the bottom,” Ilona says.

The findings from the survey suggest the likelihood of being the victim of violence increases after testing positive for HIV.

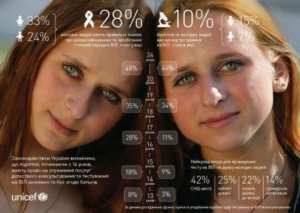

This type of attitude — that HIV is a disease just for “those at the bottom” — can manifest itself in violence against women with HIV. Violence against women is bad enough in Ukraine, but according to a November 2016 survey Positive Women conducted with 1,000 HIV-positive women across the country, more than a third (35%) of women living with HIV reported that they’d been the victim of violence from either their partner or husband, and almost half (47%) said they’d had no support afterwards. Worse still, the findings from the survey suggest the likelihood of being the victim of violence increases after testing positive for HIV.

Violence against women with HIV can even extend to their children, especially if they also have HIV. Olga Rudneva, Executive Director of the Elena Pinchuk ANTIAIDS Foundation in Kyiv, tells me about an incident in a small town in Dnipropetrovsk oblast, where a social worker started trying to raise money for a family with an HIV-positive child. The family, including the children, had stones thrown at them and were eventually forced to flee the town.

“It’s 2017, in the middle of Europe,” Rudneva sighs.

“For people like you, we have no place”

Outright discrimination against women with HIV in healthcare environments is a problem in Ukraine. The report Positive Women and other activists filed with the UN last month has several stories of HIV-positive women being denied access to health care because of their HIV status.

“In 2016, when it was time for delivery, I came to the perinatal center, but the administration refused to admit me, saying that ‘for people like you, we have no place,’” Natalia, a HIV-positive woman, is quoted as saying in the report.

Likewise, a social worker recounts how an HIV-positive client of theirs was placed in a hospital room with broken windows during the winter, on the grounds that there weren’t any other rooms available, and another spoke of how a client of hers was denied in vitro fertilisation (IVF) because of her HIV-positive status.

…the doctor started screaming at me and accused me of not telling her about my [HIV] diagnosis.

At her office in Kyiv, Svitlana Moroz walks me through the findings of the survey. The numbers tell a story of how health care providers can discriminate against HIV-positive women across Ukraine, and how many of these women don’t know where to turn for help. One-third (33%) of women, when asked whether they believed healthcare providers would keep their HIV status private, said they didn’t believe they would. Almost one-third (31%) don’t know their rights and don’t know who to talk to if they feel their rights have been violated.

In Positive Women’s survey report, one woman’s account stands out as an example of the discrimination women living with HIV can face at an institutional level.

Marina, a then-pregnant HIV-positive woman, recounted to the researchers at Positive Women that, at a gynecological clinic, “…the doctor started screaming at me and accused me of not telling her about my [HIV] diagnosis. She said she’d sue me because I could infect her, and added a few humiliating epithets… ‘So you’re a drug addict, right?’”

“I was afraid to go to the doctor for a long time because they’d judge me,” Marina says in the report. “Talking about my status was still humiliating. So I never asked for help, even when I felt pain that was getting stronger by the day. I was taken to the gynecological department bleeding, unconscious.

“It turned out to be an ectopic pregnancy. My life was saved but, sadly, I’ll never be able to have children.”

Women living with HIV aren’t always able to access the healthcare services they need. According to Positive Women’s survey, only 36% of HIV-positive women reported receiving regular cervical screening and only 32% had regular consultations with a doctor about breast cancer — even though women living with HIV have a greater risk of developing cancer.

Part of the issue, Natalia Ruda from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) tells me, is that many HIV-positive women don’t know enough about their own health to know what they could be asking for. She says that her organisation, which provides HIV testing services and treatment across Ukraine, has seen more and more women over 40 coming in and getting tested for HIV — and testing positive.

“No one’s telling them about their health,” Natalia says, “about risks, about safe sex.”

“When you feel that coldness, indifference… you feel despised”

“It’s something I’ll never forget,” this is how Ilona, the social worker living with HIV, describes her treatment at a Kyiv maternity hospital several years ago.

Ilona was in a special unit of the hospital for women with pregnancy difficulties. There were a few other HIV-positive women on the unit with her and, because of her personal and professional background, she met up with the chief doctor to offer some help.

“He screamed at me,” Ilona says. “He said: ‘You sleep around, get infected! It’s a headache to deal with you, to treat you!’”

“I learned later this was his manner with all patients with HIV during first contact, basically telling them off,” Ilona says. She tells me that this story is “quite typical,” that an HIV-positive woman’s first experience with a doctor is often aggressive and accusatory.

Ironically, Ilona laughs, she’s now friends with the doctor, but the memory of this incident still bothers her. “When you feel that coldness, indifference,” Ilona tells me, “you feel despised. You feel they’re not ready to pay to attention to you, not ready to give any time for you.”

“This is our last window of opportunity”

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, by far the largest international donor to the HIV/AIDS fight in Ukraine, had originally planned to significantly cut funding in 2017 to Ukraine. Activists were concerned that the situation in Ukraine could be a larger-scale rerun of what happened in Romania, when a cut in Global Fund money contributed to a sharp increase in HIV infection rates among at-risk populations.

Fortunately, as several activists and officials were keen to point out, the Global Fund has since stepped up with more than $120m in continued and emergency funding over the next three years. More funding has come from other sources — the Ukrainian state is fully funding opioid substitution therapy in 2017 for the first time ever and the US government recently announced it will providing almost $40m in emergency funding.

But, as Dr Natalia Nizova from Ukraine’s Public Health Center tells me, “for us it’s absolutely clear that the situation of huge donor support will not last forever,” given that Global Fund is expected to withdraw most of its funding from the country in 2020. Effectively tackling and turning around Ukraine’s HIV epidemic will require transition planning and cooperation with advocacy groups like Positive Women.

Above all, it will require working closely with Ukraine’s politicians and the country’s cash-strapped state to ensure HIV remains high on the agenda so that Ukraine, in just a few years, can take over and effectively fund its HIV treatment and prevention programmes. “This is our last window of opportunity,” says Dr Nizova.

But Svitlana Moroz says women with HIV are still struggling to have their voices heard. Ukraine’s current national AIDS council and other committees have no HIV-positive women on them, she says.

“It’s very important to mobilise and empower women living with HIV,” Moroz tells me. More women living with HIV, she says, need to be invited into policy and programme discussions across Ukraine, at all levels of government.

Moroz, for her part, sounds determined to be part of the conversation, whether HIV-positive women like her are invited to the table or not.

“We say: ‘nothing for us without us.’”

The piece was originally published on opendemocracy.net

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

The fight against HIV. One more victim of Maidan, together with Ukraine’s economy which is half the size it was in 2013.

The Ukrainian economy is growing despite the ongoing war and despite losing a huge portion of its industrial base in the Donbas. Compared to Russia, Ukraine’s economy is a shining star. I am convinced that the Ukrainian government will increase funding for the fight against HIV, as the economy becomes even stronger.

Jeff, you are one totally delusional guy! The Ukrainian economy is in total shambles and not even billions of dollars of bailout from US imperialism and its allies is not helping much at all.

I suggest that you google the increase in the economy. There are plenty of articles chronicling the percentage growth.

The opposite is actually true. The per capita income is continuing to incline downward.

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/ukraine/gdp-per-capita-ppp

The loans from the IMF and US government distort the figures a lot and are used to give the distorted illusion that Ukraine’s economy is actually slightly growing, when it truly is not. The war against Donbas has itself alone destroyed billions upon billions of dollars of infrastructure there. That is no sign of a growing economy.