Although Greece has been at the forefront of media attention in the past week’s, Europe’s unprecedented migration crisis continues. Many Western European countries, who have decades of experience with incoming mass migration, feel they have exhausted their solidarity and EU member states in the former Eastern Bloc are equally, if not more, resentful towards potential newcomers. Ethnically homogenous Central European member states – Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary – have been particularly opposed to the idea of accepting European refugee relocation quotas and housing a small share of the masses of migrants attempting to reach Europe in the pat months. Hungary is building a fence on its border with Serbia, Islamophobic campaigns are on the rise in the Czech Republic, Poland continues to be unable to agree on the number of refugees it will accept, and anti-immigration sentiments have fuelled marches of extreme nationalist groups in Slovakia. In these countries where there is little experience with incoming migration, fear of the unknown easily breeds hatred. Yet it is precisely these countries that would benefit from reflecting on their own history and the emigration experiences of their citizens during the period of the Cold War, when countries in the West opened their doors to them.

Solidarity with migrants in the era of the Cold War masked other ideological projects of Western countries. But if the European Union has an ideology, it is precisely one of solidarity, equality, and respect as expressed in its founding principles. Yet the EU is unwilling to assert that ideology.

Here is a story: my parents emigrated from Czechoslovakia in 1981. With only a vague idea of how they would make it to the other side of the Iron Curtain, they departed on holiday to Yugoslavia with the intention of not coming back. After a few days of unsuccessful attempts at scaling the wall separating what is today Slovenia and Italy and crossing the border on foot, they finally made it to the other side in the boot of a kind Austrian student’s car. In Italy, after yet another unsuccessful attempt to cross the border to Austria, they were navigated to a refugee camp, from where after six weeks, through the help of the International Rescue Committee, they flew to the United States. There, they were granted the status of asylum seekers, were given temporary housing and assisted with looking for jobs. Within five years, they were US citizens.

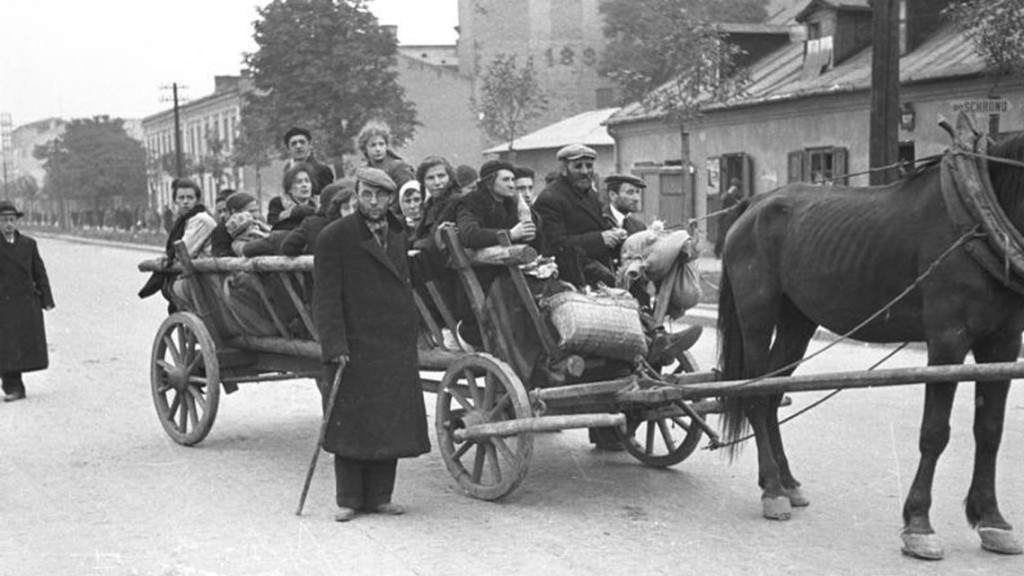

I mention this story here because it sounds incredibly straightforward compared to what is happening at Europe’s doorstep today. Even though many non-governmental organizations continue to help both refugees at Europe’s borders and within the EU itself, their efforts are being systematically thwarted by the lack of a European consensus on migration policy. The obvious objection here is that the political situation before 1989 was different and there is no denying that it was. Countries in the West at the time were much more willing to grant Eastern European migrants asylum as part of the ideological war they were waging with the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence. At that time, the citizens of those EU member states of Central Europe – the Visegrad Four – who are now so opposed to accepting refugees, were fleeing from countries where their freedoms were being curtailed, though not necessarily their basic material needs. They fled from being prevented from freely expressing their opinions, from practicing their religion, their profession, or expressing their sexuality. But the vast majority of them had a roof over their head and even a job, even if the conditions of both were not always dignified.

Today’s migrants often suffer from the same intellectual injustices, but what’s more, they are fleeing from conditions that are so abhorrent that they would probably accept living in state socialism, were it still around. What does this say about the current regime of values in Europe, which does not deem this a sufficient enough cause to extend its generosity? Firstly, it points to a basic prejudice whereby those who flee for intellectual reasons are often considered more worthy than so-called economic migrants. Helping victims of persecution and accepting “political migrants” validates Europe’s project of extending democratic values. The fear of economic migrants, on the other hand, is a form of denial, of refusing to think through what it means to live in a global economic system that produces gaping inequalities.

Solidarity with migrants in the era of the Cold War masked other ideological projects of Western countries. But if the European Union has an ideology, it is precisely one of solidarity, equality, and respect as expressed in its founding principles. Yet the EU is unwilling to assert that ideology. No one wants the return of the bi-polar world of the Cold War, where the word ideology stood for the tools through which either side tried to gain the upper hand over the other. But ideology is not something that disappeared with the collapse of the Eastern Bloc; it is not something we can opt out of. It is the very fabric of our daily existence, the system of values that organize society. What are European values if Europe does not stand for them? The problem that Europe faces is that it is experiencing first and foremost a crisis of its own values and non-European migrants are bearing the burden of the externalization of Europe’s internal conflicts.

By refusing to assist with resolving the migration issue, Central European countries are attempting to opt out of the European project they signed up for. These countries need to acknowledge how their own histories have been positively shaped by emigration. Before 1989, hundreds of thousands of citizens emigrated to the West from Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary. Both ordinary citizens and members of the opposition sought asylum in the West. Many then returned to their home countries after 1989 with valuable experiences that aided the building of more democratic societies. The figure of the exile has held an important place in the intellectual traditions of these countries and it was also the international connections and expertise of exiled opposition activists that aided those struggling for freedom at home. Significantly, one of the freedoms that dissidents strove for before 1989 was also the freedom of movement. When the media reported that the organizer of anti-immigration protests in Bratislava is himself an economic migrant living in Italy, the hypocrisy seemed nothing but comical. Central European countries which continue to refuse to share responsibilities in the migration crisis now find themselves in a similarly hypocritical and laughable situation.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

Problems with the ideological discrepancies of the new surge of migrants would be of foremost concern. With the introduction of an authoritarian theocratic ideology that is diametrically opposed to “western” democracy, and in fact wishes to overthrough/repace it, the unrest of the “host” populations will only increase. The friction caused by a clash of cultures should not be unexpected. The attendant crime rates are an expected consequence of a mixture that refuses to be homogenized. Although the altruistic motives should be commended, this should be seen as an utter failure in practice and a difficult situation that will take decades to remediate.