By targeting property, student activists can gain leverage in negotiations with university management to effect real change on an institutional level.

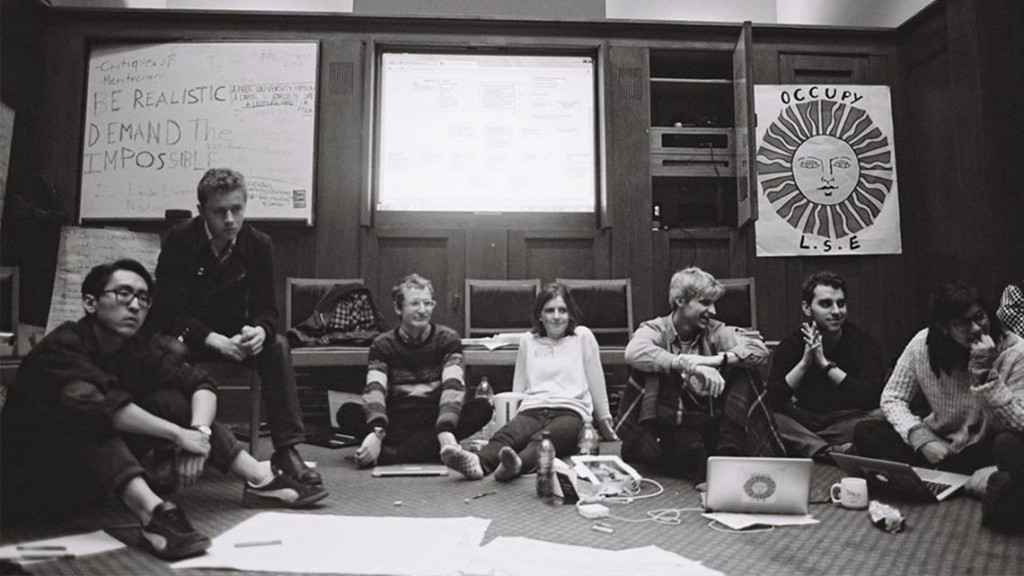

[On the 17th of March students occupied the Vera Anstey room of the Old Building of the London School of Economics (LSE). The LSE occupation thus joins a recent wave of occupations and protests at universities both in the UK (King’s College London, Goldsmiths, University of the Arts London) and abroad (including Amsterdam and Toronto). These actions are united by their rejection of the marketization of University education and a shared conviction that institutional change can only be achieved through direct action. The Occupation of LSE continued until the 2nd of April when it was suspended due to a fire in the vicinity. Between the 17th of March and the 2nd of April, the occupiers organized regular workshops in the Vera Anstey room dealing with pressing political and social questions. They engaged in constant dialogue with LSE management and held daily General Meetings to discuss these negotiations. The Vera Anstey room was re-occupied after the Easter break in order to continue deliberations on the direction of higher education in the United Kingdom and to resume negotiations with LSE management.

The LSE Occupation is demanding universally accessible education and a public commitment on the part of university management not to raise tuition fees. Further demands include public access to lectures and timetables, and the recognition of the Free University of London – an open and inclusive space for free education within LSE. The campaign also calls for improved working conditions of service staff, the de-hierarchization of academic structures, and an end to unethical investment on the part of the university. To achieve these changes, the occupiers are proposing to create an Independent Review Committee, formed of students, academic, and non-academic staff in equal parts, which will investigate the current system and propose reforms. The set of demands thus speaks to wider concerns about the commercialization of higher education in a neoliberal economic climate, which reach well beyond the borders of the UK, not least because non-UK students form of a significant proportion of the student body (nearly 20% of all students come from abroad, while at some high-demand institutions, such as LSE, this is up to twice as much). The challenges that universities in the UK face impact a much larger international community.

With the highest tuition fees, the UK is Europe’s most expensive public education system, significantly financed through student debt – a situation which calls into question the very purpose and meaning of public education.

Following the unpopular decision of the Conservative-led coalition government to raise tuition fees for a year of undergraduate study from £3,375 up to £9,000 per year from 2012, students in England in particular (education remains free or significantly cheaper for UK nationals in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) have increasingly expressed their disagreement with what they see as a privatization of education. Student protests have therefore focused largely on free education as a fundamental right and the abolition of tuition fees. Other rallying issues have included the disproportionately high salaries of academic management, the inherent elitism of the university system, postgraduate students’ working conditions and the casualization of academic labour, the marginalization of the humanities, and, more recently, divestment from companies involved in the exploitation of fossil fuels. Although the rise in tuition fees has not dramatically changed the number of university applicants as some predicted, the new system has significantly increased the debt burden of students, to the extent that many are now not expected to repay their student loans. The changes to the educational system caused students to take to the streets in mass marches, most violently in November 2010, when protesters smashed the windows of the Conservative Party headquarters.

LSE students, together with their colleagues in other occupations, have adopted a different tactic. The decision to occupy has important implications. Recent years have seen a return to forms of direct action more often associated with political movements in the 1960s. This has meant a shift away from demonstrations as the go-to method for applying political pressure, and an increased readiness to adopt methods that have a greater emphasis on duration and more willingness to impede university management in a targeted way. In Amsterdam this has meant occupying physical spaces the university management had decided to sell off since February 2015. At LSE, the occupation has targeted a room used for management meetings.

There are significant advantages to this form of action over demonstrations. In the first instance, occupations intervene in a more direct way than demonstrations. Quite simply, they are more difficult to ignore since they are an ongoing presence as opposed to a one-day event. The site of the occupation itself becomes a base of operations, allowing meetings and workshops to be held more easily and over a longer period of time. In addition to these practical advantages, there is also a sense in which occupation trumps demonstration insofar as the latter no longer has the same traction in today’s political environment. More precisely, the danger with demonstration as a method is that it is universally accepted as a legitimate form of political protest. In such a situation, demonstrations that take place are ultimately impotent. Students take to the streets, perhaps university management makes a brief press release, but afterwards business-as-usual resumes. Moreover, management can even cynically refer to the demonstration in their prospectus as evidence of the vibrancy and political engagement of their student community.

Occupation as a method of direct action has the distinct advantage that it actually forms an interruption of university life. But perhaps more important than this, it is far more politically significant than a demonstration since it does not only aim to be visible (as a demonstration does) but it also explicitly sets out to target property by reclaiming physical spaces. As such, occupations strike at a weak link in the ideological edifice of the university as an institution. The occupiers demonstrate to themselves and others that property relations are contestable, that the question of who can legitimately enter a space can be reopened. The challenge is far more difficult for the university to absorb. From the perspective of university management, a demonstration can simply be ignored, whereas an occupation cannot be allowed to go on indefinitely, but equally cannot be stopped without a real risk of negative publicity. The shift from demonstration to occupation as a method of political action should be viewed as resulting from a recognition that it is insufficient to simply proclaim one’s message (be it objection to tuition fees, calls for divestment, or demands for more fundamental changes in the management structure of universities) from the street; rather, one begins by occupying a space and using it to create a parallel institution which embodies the values they hold. This has been a common characteristic of occupations in both Amsterdam and London which have led to the establishment of the New University and the Free University of London respectively.

The Free University of London currently criticizes the marketization of higher education and promotes the idea of an education system that is free for all. The space itself (the occupied Vera Anstey room) allows this model to be put into practice by the occupiers themselves. This is combined with decision-making practices based on participation and consensus that are inherited from the broader Occupy movement. The question currently faced by the Occupation is twofold: firstly, how can the concept of the Free University be fleshed out more fully, and secondly, the related challenge of making the occupation durable and influential. In a sense, these two concerns are connected. If the Free University is able to articulate a concrete positive agenda which is attractive to current students, this will in turn lead to greater momentum for the occupation and strengthen its position in negotiations with management.

What might this positive agenda look like? Given that the occupation is focused on reclaiming property from market interests, one possible intervention might involve targeting intellectual property specifically. A first step in this direction could be, for example, producing high-quality uncopyrighted PDF documents of all core texts on LSE modules. This could be the beginning of a wider project to make educational resources freely available. Distributing ebooks and software free of charge from the Vera Anstey room could provide a valuable service for students and win more support. Whether or not the occupiers actually decide to take this route, they will certainly need to escalate their activity in order to maintain pressure on LSE management. The worst outcome would be for fatigue to set in among the occupiers and for management to tacitly cede the Vera Anstey room without meeting the occupiers’ demands. The Occupation must avoid the twin pitfalls of, on the one hand, losing steam and simply dissolving, and on the other hand, allowing itself to become institutionalized by an unreformed and unrepentantly neoliberal LSE who would then shamelessly advertise the Occupation to prospective students as evidence of the thriving, politically engaged student community. The Occupation has the advantage insofar as it is able to escalate its action whereas LSE management’s fear of negative publicity prevents them from forcibly evicting the students. It is precisely the threat of escalation that allows the occupiers to resist being co-opted as ‘activists in residence’.

By Jack Reilly and Veronika Pehe.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)