Following demonstrations by the feminist movement against Donald Trump, Nancy Fraser, now Professor of Philosophy and Politics at New School for Social Research in New York, signed – along with many others such as Angela Davis and Rasmea Odeh – an appeal for a “99%” feminism, one that is transnational and anti-capitalist.

Her work tries to build an inclusive ‘majority’ feminism that rejects neoliberal cooption. With several decades of academic work, in which she has covered issues such as justice, capitalism and feminism, Fraser is today one of the most recognised intellectuals within critical thinking. A defender of Bernie Sanders’ political strategy, a critic of Clinton, and a fervent opponent of Trump, in this interview she analyzes the current political situation in detail, positioning herself in favor of a “left populism” that opposes both “progressive neoliberalism” and “reactionary populism.”

What is your assessment of the first hundred days of President Trump’s term? What can these months tell us about his project, its limits and possible resistance to it?

I would say that there are two aspects to note: on the one hand, the ease with which the more conventional factions of the Republican Party have managed to recover and disarm the populist dimension of the campaign. It is basically backing off on a number of issues, such as NAFTA, which Trump no longer plans to abandon, but to renegotiate. It is being drawn into a free trade agenda and low taxation. There are no half-serious indicators of infrastructure projects, which Trump included in his campaign as a formula for job creation. He is making all those dreadful media “gestures” (such as the veto of Muslims, etc.), knowing very well that they will be revoked by the judiciary system. But it seems to be his way of giving something to the workers who, on the other hand, he is deceiving in each of the economic measures that he takes. In fact, if we recall, we will see that he won 17 Republican Party primaries with a speech appealing to workers. The fraud may not be surprising, the speed with which it is happening is.

The biggest and most powerful part of the resistance to Trump is trying to get back to Obama or to Clinton.

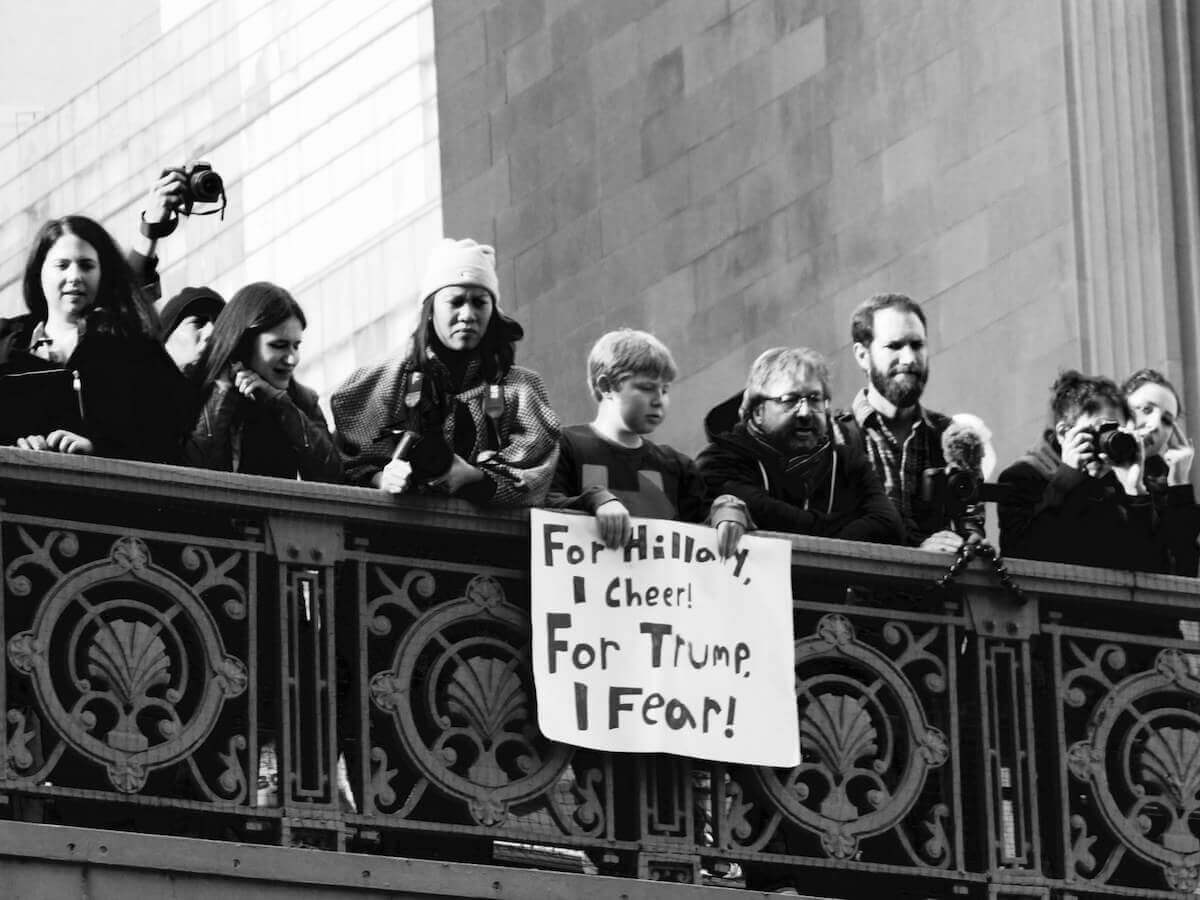

On the other hand, there is the question of opposition, because when you make all these gestures, you produce a lot of fear and anger at the same time. In fact I think we can say that there is a mobilised opposition against Trump, and that the country is more politicised than it has been in years. However, it is an incipient opposition, and I would say ambiguous. Probably the biggest and most powerful part of the resistance to Trump is trying to get back to Obama or to Clinton. This is an opposition that seeks to restore the status quo.

From my point of view, this is really insufficient and even highly problematic, since the previous status quo is exactly what produced someone like Trump. So there is a vicious circle: if we go back to that, we will have even worse Trumps. The other possibility is that the resistance moves in the direction of a left populism, like the one that Bernie Sanders effected in his campaign. In that case, it would not be a matter of restoring normality to Trump. I think the opposition is hovering around these two possibilities and that there has been an opening big enough for the voices of a left-wing alternative to be heard. Nonetheless, there is still a sort of inertia in our societies that pushes towards what I call “progressive neoliberalism.”

Feminist Organising and the Women’s Strike: An Interview with Cinzia Arruzza

You recently supported the candidacy of Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the French elections, but ultimately the vote had to be made between Le Pen and Macron. I would like to connect the French case with what you argued in a book published recently, where you explain that the dilemma between progressive neoliberalism and reactionary populism can be understood as a “Hobson election.” Could you develop this a bit more?

I think there are striking parallels between the last French elections and the 2016 presidential elections in the US. Here we had an apparent collapse of the two main parties, which resulted in the loss of control of the votes of the popular classes by the bureaucracies of these parties. There we had the spectacular victory of Trump, who came almost from nowhere, who had never held an elected position, without previous political experience, but who finally managed to decimate the candidates handpicked by the party leaders, who clearly wanted someone like Rubio.

In the French case Le Pen was our Trump, Macron our Clinton, and Mélenchon our Sanders.

Trump succeeds in articulating a reactionary populism, which is a combination of a rejection of a growing financialization of the economy, a defense of industry and its workers, and a more unpleasant use of the immigrant population, Muslims, Latinos, along with misogynist and racist rhetoric. Meanwhile, on the Democrat side, we had Sanders facing Clinton, the candidate chosen by the party apparatus, which we later learned that although it was supposed to remain neutral, favored Clinton over Sanders. In this scenario, Clinton embodied progressive neoliberalism, Trump reactionary populism, and Sanders, what I would call progressive or leftist populism. For Sanders, the idea was to mix an anti-racist, anti-sexist and pro-immigrant “recognition policy” alongside a “distributive” anti-Wall Street policy in favor of the working-class.

Mutatis mutandis, we can say that in the French case Le Pen was our Trump, Macron our Clinton, and Mélenchon our Sanders. In both cases, what was eliminated was the left-wing option, in part because many were stuck behind progressive neoliberalism out of fear and in opposition to right-wing populism. In that sense, the situations in France and the United States were quite similar and I signed, along with many others, a letter urging the French electors to avoid the same error that had been committed here.

Both progressive neo-liberalism and reactionary populism are terrifying options, which in turn mutually reinforce each other.

I think we should break the circle. With “Hobson’s choice” – which is an idiomatic expression of English – I wanted to express that both progressive neo-liberalism and reactionary populism are terrifying options, which in turn mutually reinforce each other. While they are on the one hand different and opposing options, on the other hand, each one creates the conditions for the other to become stronger. Therefore, a third option is necessary that breaks the schema. I think at least in the US not everything is lost. Sanders is still one of the most popular and valued politicians. He does not seem to want to go anywhere and I hope that the forces he has been able to mobilise will not disappear either.

In an article published earlier this year in Dissent magazine, you argued, as now, that what we need is a progressive populism. Why do you think populism is the answer and what would the benefits and limitations of the populism as a political logic?

For me, ‘populism’ is not a negative word. Jan-Werner Müller published a book last year saying that populism is inherently undemocratic, excluding, persecutory, etc. I do not agree with this and I think it is a poor definition of the term. I feel much closer to someone like Ernesto Laclau, who saw populism as a logic that could be articulated in many different ways. It is true that there are reactionary populisms, but this need not always be the case.

On the other hand, for me, populism is not the last word, it is not a sort of ideal to be reached, but rather a transitional political phase, almost like what the Trotskyists called a “transition program.” What I want in the end is the emergence of a democratic socialism. That said, the language that emerged with the Occupy movement, and which now I attempt to adapt to feminism, is that of the 99% versus the 1%. This is clearly a populist rhetoric, it is a language different to the one we use when we speak of global capitalism, of the working class, although these terms are possibly more accurate in describing how our society works. I think there is a chance to win and convince more people now using populist rhetoric, but of course, it has to be a left-wing populism.

There was a point where Sanders and Trump overlapped a bit and it was in the discussion about what Sanders called a “rigged economy“, a term Trump appropriated, because it is obviously an expression that is understood immediately. If you start talking about the dynamics of exploitation and expropriation of capital, it becomes more complicated. So for me it is a great start to begin changing political culture, to make people think more structurally about what does not work in our society.

Progressive neoliberalism superficially articulates immigrants, people of color, Muslims, LGTBIQ as the “we” and turns the white man into a “them.”

The 99% is evocative, and its main function is to suggest that white worker victims of deindustrialisation and imprisoned and expropriated African Americans, are potentially part of the same alliance. And that there is an oligarchic group, let’s call it global financial capital or whatever, which is the common enemy. This is an immense re-organisation of the political universe, a different way of articulating a “we” versus “them”. Progressive neoliberalism superficially articulates immigrants, people of color, Muslims, LGTBIQ as the “we” and turns the white man into a “them.” This is a horrible way of dividing us, a form that only benefits capital. For me populism is a way of changing the game. What makes it progressive is that it is inclusive, the 99% is a very inclusive number. For the moment it is a great discourse around which to mobilise and organise.

In the construction of this counter-hegemonic populist and progressive force, there seems to be a tension between the national and transnational scale. Progressive neoliberalism is usually presented as open to cosmopolitan diversity, as opposed to the values defended by a reactionary populism. How should a leftist populism situate itself in this debate? How should the tension between its national-popular character and the transnational scale interact?

Any form of progressive populism has to be internationalist and work in building transnational coalitions and forces.

This is a very complicated question and I am not sure I have a fully worked answer, but it is one of the most important issues to deal with. I think that in the end what is needed is a greater internationalism on the left, we have to go back to the old idea of workers’ internationalism until we achieve transnational labor and environmental protection standards. It will not be possible to solve these problems in any other way. I would say that any form of progressive populism has to be internationalist and work, in that sense, in building transnational coalitions and forces, as well as working to protect the rights of territories as they currently exist.

You have also said that you believe that we are in a moment of ‘interregnum’, an unstable political situation but one also open to change. Starting from Jean-Claude Juncker’s statement when he said that “we know what to do, but we do not know how to be re-elected after doing so”, would you say that among the elites there is a lack of a solid narrative and that this somehow puts them in a more defensive than offensive position?

Yes, I agree with this diagnosis. Not only did the narrative of Reagan and Thatcher disappear, but also its continuation, that of Blair and Clinton. There was for a time an attempt at “new labor”, a third way, of which Obama was also part. Here, Bill Clinton was the principal founder and the architect of the Democratic Leadership Council, which took the Democratic Party in a different direction than the traditional one, linked to the New Deal. They had a narrative but, above all, a strategy: they said that the demography of the country had changed to such an extent that the white working class was no longer central, that elections could be won by appealing to the upper classes, the suburban middle classes, the technology and entertainment sectors, minorities and women. His narrative was progressive neoliberalism.

What happened in 2016 was that the narrative was torn apart, so now they have neither the Reagan-Thatcher bloc nor the Clinton-Obama bloc. What do they have? Well, I would not say that they are incapable of proposing something new, they are very creative people, and I am sure that in their think tanks they are trying to foresee the next movement, but so far, it is not so clear. My intuition is that they will try to revive progressive neoliberalism under new, sexier figures. Hillary Clinton did not work that way, so they’ll try to find someone who can do that. And as I said before, the opposition to Trump is ambiguous and probably a part of it could be convinced again if a leftist, compelling and broad narrative does not materialise. But there is definitely a crisis of legitimacy and hegemony and they are looking at how they can reconstitute themselves.

They will look for something else and that something will not be another form of progressive neoliberalism.

It’s an opening moment, for the Le Pens and the Trumps, but also for the Sanders’ and the Melénchons. The second thing that makes this time one of interregnum is to see that someone like Trump has been unable to establish himself as an alternative. In this case, where he cannot or does not want to offer the working class what he has promised them, the question is for how long they will continue to be satisfied with his media gestures. They probably will not wait forever, they will look for something else and that something will not be another form of progressive neoliberalism.

Assuming that populism is a political logic that can lead us in an emancipatory direction, would you say that it should establish a theoretical and political dialogue with feminism? How should feminist movements participate in the construction of this populist logic? Is your commitment to “99% feminism” going in this direction?

Yes, that’s exactly the idea. I believe that every emancipatory movement today, not just feminism, has to acquire a populist dimension. Most social movements have been co-opted by neoliberalism. The dominant feminism in the US and in many other places has been to “break the glass ceiling,” known as “lean in feminism” (from the bestseller published in 2013 by Facebook’s Director of Operations, Sheryl Sandberg, called Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead), which, in fact, is the 1% feminism. Just as Sanders speaks to the victims of the rigged economy, and just as Occupy was speaking on behalf of the 99%, feminism and other social movements now have the opportunity to say: let’s break up with the 1%, we do not want that feminism, we want a feminism for migrant women, for domestic workers, for all those who take care of their jobs and home, for women with precarious jobs, for all those who try to find ways to take care of their children, their families and their communities at the same time, as they are forced to work more and more hours for less money.

I see 99% feminism as a feminism that moves away from neoliberalism and as part of a larger leftist populist movement.

I see the struggle for universal public healthcare, one that covers of course maternity leave and free abortion, as part of 99% feminism. I see 99% feminism as a feminism that moves away from neoliberalism and as part of a larger leftist populist movement. And I think that every social movement, from the LGTBIQ movement to environmentalism, must be re-thought in terms of the 99%, and abandon the co-opted versions, such as “green capitalism” or the defense of homosexual marriage with little or no interest in social rights. Any movement is a potentially allied in the construction of a counter-hegemonic bloc, but only if they abandon neoliberal rhetoric and move in a new direction. And of course the labor rights movements have to participate, the unions are not very strong in the US, but there are other fights like the Fight for 15 which are strong enough.

Last year in the New Left Review you published an article called ‘The contradictions of capital and care’, where you argued that we were going through a new mutation of capitalist society, and that there could be a possibility of reinventing the reproduction-production division and the model of ‘family with two providers’. Could you make some guesses about what specific demands the feminist movement should make in relation to the issue of care and social reproduction?

Yes, I think this is one of the main tasks of 99% feminism. I am convinced that a feminism that concentrates all its attention on production, on getting more women into the labor market, and neglecting what happens in the field of reproduction is moving in a bad direction. Both spheres are separate and yet intertwined, which is part of the difficulty. We need a new way of thinking about their relationship.

A good starting point would be not to put them in absolute contradiction, something that happens now and that can be seen in phenomena such as egg freezing or technology mechanical pumps to extract breast milk. Women are placed in situations where it is impossible for them to have a career and at the same time have children before the age of 45. It would also involve measures such as reducing working hours, decent wages that could support a household and not a person, since not all homes count on or want to have more than one supplier. The idea would be to formulate employment and welfare policies under the assumption that we are all supportive subjects and caregivers. If we make this the ideal of citizenship, then we will have a completely different set of policies.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)