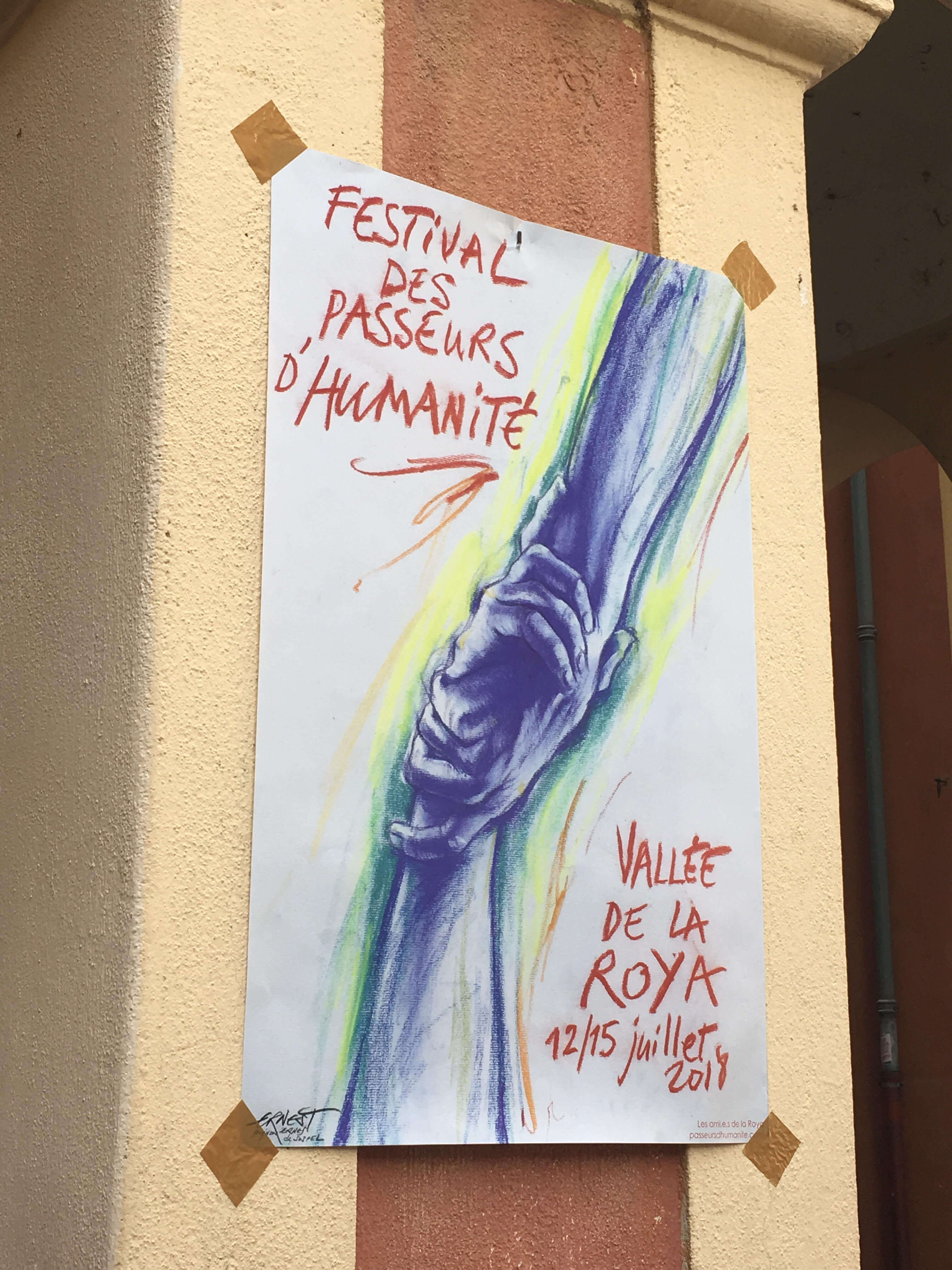

The summer festival season is underway across Europe. Over the course of a few days, people come together to share a common passion. While lovers of music were celebrating at Cruilla in Barcelona and Rock in Roma, lovers of humanity had gathered in the Roya Valley, where the first “Festival of humanitarian smugglers” took place in four villages along the Franco-Italian border. In this idyllic mountain setting, citizen activists debated, visited art exhibitions, and danced to live music, all related to theme of migration and welcome. The festival is evidence of how European citizens themselves are welcoming migrants and calling for new migration policies, and in doing so they are enacting a form of European citizenship as solidarity.

The event had all the trappings of a typical festival: a four-day festival pass (for a donation of any amount), souvenir t-shirts, beer in reusable plastic cups. But the celebrities featured were not the usual festival headliners. The crowd went wild for Cédric Herrou, a local farmer who has hosted hundreds of migrants and been brought to court for his actions; José Bové, a deputy in the European Parliament known for his anti-globalisation activism; Mireille Damiano, a lawyer who defends migrant minors in irregular legal situations. As Damiano said, “we’ve been treated as smugglers so often that for once claiming the status of smuggler is good!” They led lively debates along with festival attendees, who had come from the villages of the valley, across France, and some from across Europe. Still, notably absent from the festival were migrants and refugees themselves, with only a few in attendance. To show true solidarity with migrants, those assisting migrants must also make space for their voices.

Since mid-2015, France’s border with Italy has been closed, ostensibly as a security measure after several terrorist attacks in France. However, the consequence for migrants is that their journeys become even more dangerous, and they often have to rely on others for help to cross the heavily policed border.

For residents of the valley, the border does not exist, they are used to the valley being a space of transit and exchange.

At the festival, Herrou explained that “I didn’t go to Italy to pick up people, I went in my valley.” But for the state, the border is enforceable, so police are present throughout the Roya Valley, even on the mountain path leading to Herrou’s farm, where they check the ID documents of anyone going to his house.

Residents of the valley are assisting those who arrive with food, shelter, and help with legal processes. However, both EU and French law criminalize actions that facilitate the illegal entry, stay or circulation of foreigners. Violations of this law are known as a “délit de solidarité”, an offense of solidarity, and residents of the valley have faced legal consequences for their humanitarian actions to assist migrants. Despite this hostile climate, residents of the valley continue welcoming migrants in their capacity as individuals and through associations like Roya Citoyenne. Those helping migrants claim that doing so is their duty as French citizens, an act of fraternité to protect the human rights of vulnerable people.

The festival that took place in the Roya Valley celebrated these humanitarian smugglers as humanitarian citizens, and it was one among many European solidarity movements with migrants. During the same weekend as the festival, on the other side of the border, a demonstration took place in Ventimiglia denouncing the brutality of European migration policies and calling for a European residency permit for migrants. Such a permit is based on a conceptualization of Europe beyond the nation state, in the same vein as campaigns for European citizenship that is not based on a national identity. Ventimiglia was also the starting point of the Solidarity March for Migrants, which traversed over 1400 kilometers across France to Calais and on to London from April to July 2018. Hundreds of people joined the march, calling to welcome migrants, end the “délit de solidarité” and denouncing France’s closed borders with Italy and the UK.

A major victory these activists was the recent decision of the French Constitutional Court affirming “fraternité” as a constitutional principle. The ruling stated that “the concept of Fraternité confers the freedom to help others, for humanitarian purposes, without consideration for the legality of their stay on national territory”. While this is undoubtedly good news, there are some important concerns. First, there is the issue of compensation: the humanitarian action cannot have any direct or indirect benefit for the person performing it. However, compensation is not explicitly defined as financial gain, which leaves a grey area. One court in France has even ruled that if the humanitarian action contributes to a person’s activism that can be considered compensation. The court decision also leaves it up to the legislature how to balance the principle of fraternité with public order, which could still result in measures restricting assistance as part of the political agenda securitizing migration.

More troubling are the borders firmly in place that are evidenced in this decision. This principle of fraternité only applies in France, and it is not valid if one helps someone to cross a border. Not even two weeks after the court decision, on July 17th, four people were summoned to police custody in Briançon, accused of helping people to cross the border. Three other people in Briançon are awaiting trial on similar charges on November 8th. Despite the court’s decision on fraternité, it seems the délit de solidarité still exists.

Many European citizen activists claim that within Europe such obstacles to migration should not exist, and solidarity with migrants has become a Europe-wide struggle that goes beyond borders.

Although the 2002 EU Facilitation Directive that criminalises any act that facilitates the entry, transit or stay of unauthorised foreigners does include a provision for humanitarian exceptions, few states have put such measures in place. Activists across Europe have launched We are Welcoming Europe, a European Citizen’s Initiative calling for an end to the criminalisation of humanitarian assistance to migrants across Europe. The ECI is “the first transnational instrument of participatory democracy allowing one million citizens to invite the Commission to initiate legislation on a matter those citizens deem important”. It is a key example of people using their rights as European citizens to defend the rights of non-citizens.

The spiraling securitization of migration that is hardening Europe’s borders to external migrants also has perverse consequences for freedom of movement for citizens within the EU. Despite freedom of movement rights in the EU, citizens face difficulties when migrating to another EU country, and there are even more challenges when internal EU borders are closed. The ACT4FreeMovement initiative is campaigning to defend mobile citizen rights in Europe, which benefits Europeans and immigrants alike.

Regardless of how fraternité is eventually legislated in France, across Europe citizens are performing fraternité beyond borders in their acts of solidarity with migrants, proving that the citizens of Europe can be welcoming even when the state is not. Where politicians have failed, ordinary citizens are setting an example of what it means to be a European citizen.

Janina Pescinski is part of the ‘ACT4FreeMovement’ program in support of the free movement of EU citizens. She will participate at the Campus of European Alternatives starting this week in Florence. The Campus of European Alternatives 2018 brings together activists and opens a space for exchange, reflection and action for both the participants of the summer school and of European Alternatives’ training programs in 2017 and 2018: ACT4FreeMovement and Countering Hate and Far Right Radicalism in Central and Eastern Europe. It aims to be the first step to build a transnational community of activists and researchers which reflects on new political trends, shares experiences and strategies, explores what transnational activism is and plans next steps for cooperation, campaigns and actions for a joint response to counter the far-right in Europe and beyond.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)