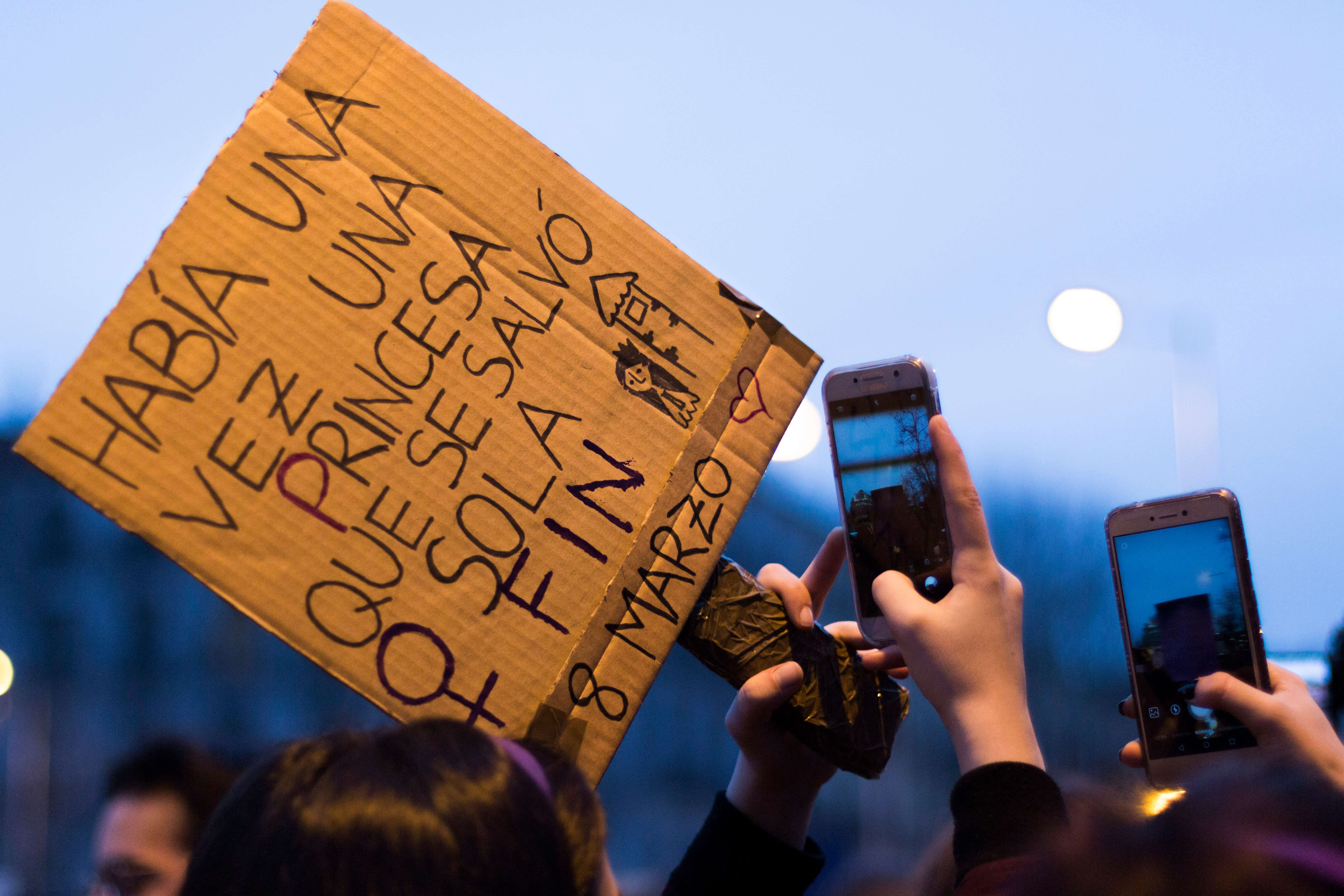

According to the BBC 5.3 million women joined the Women’s strike last 8 March in Spain. What started as a minor movement gathering a few women with slogans on the streets, ended up as an overwhelming social success covered by all mainstream media inside and outside Spain and with all politicians, including the President, speaking about the feminist march that made history. But is this all? Can we clearly and undoubtedly call this a historical success for feminism? When politicians and political parties from the Right, start appealing to feminism, alarms go off. When a collective of Black and racialized women in Spain refuses to join the national feminist actions organised for the 8 March, we need to review, as feminists, where the movement is and where it is heading.

In Spain, the collective Afroféminas decided not to join the women’s strike, arguing that, within the feminist movement, a privileged white majority neglects the problems of women of color. This observation has led to the development of a specific feminism of racialized women who look after their interests without depending on a supposed “global feminism.” “Feminisms like that of Femen do not seek the abolition of patriarchy or other systems of domination. Its goal is to raise white women of middle and upper class to the same level as white men, reinforcing racial and social division. Their feminist liberation is imperialist, western and colonialist,” says to Pikara Magazine Fania Nöel, a militant with the French Afrofeminist collective. What Nöel’s comment reveals is that the struggles faced by racialized women need to be considered a priority, as intrinsic claims in the feminist movement, and not a second level issue to be dealt with when the need arises, once the objectives of more privileged groups have been accomplished.

Now that the movement is acquiring the visibility that many of us were fighting for over years, it is our responsibility to reflect what this feminist visibility means from a neoliberal, western, white and capitalist perspective. On the debate about whether or not “mainstream feminism” can help the movement or instead, lead to emptying it of political and theoretical reflection, the past years have proved that more and more women are joining the movement to defend their rights and debate about it. The #GirlPower all around the internet, the #MeTooCampaign, the slogans on #TheFutureIsFemale, but also Femen as a collective. Even if one can see all of them as examples of great steps towards a greater feminist visibility, even if one sees this as a victory for the feminist movement, the fact that it’s acquiring this level of hegemony should also lead us to reflect about what the next steps should be, and review what and who is being left to the side. The problem of a mainstream feminism is not that it might lose social criticism in the process of becoming more visible, is that it risks alienating and failing to speak for groups considered as non privileged. And so? What needs to be done from a white, western, cis and heterosexual perspective?

Intersectionality is a buzzword that has been resonating recently in contemporary feminist activism to point out that a feminism that is mainly (or only) white, western, middle class, cis-gendered and able-bodied, represents just one faction or section of reality, excluding the experiences of all the multi-layered facets in life that women from different backgrounds face. The term was first coined in the late 1980s by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw with the purpose of bringing marginalised voices from the periphery to the center of the feminist movement by highlighting the coexistence of different types of oppression. However, even if there are many white feminists that identify themselves as intersectional, it is still difficult for them (for us) to get involved in anti-racist policies and they (we) tend to expect black or racialized women to choose between their identities of race and sex in what is proposed as an exercise that would prioritise both fights.

Solidarity and sorority are keywords in feminism, but they need to come not just in theory but in practices too. Prioritizing struggles does not go in the line of these words. Sisterhood cannot exist if white women do not realise that we cannot continue ignoring the impact of racism. This goes beyond acknowledging the importance of visibility and diversity in certain groups, collectives and actions. This means deconstructing a behavioral pattern of oppression that we have internalised as part of the patriarchal society we live in. Expecting racialized women to join the general strike for the sake of solidarity with other women and “Feminism”, is the opposite to sorority because it ignores the struggles of race. This is a battle that we need to work on at a personal level but also from our collectives: review where we situate ourselves in the existing intersections between privileges and oppressions, whether from a class, sexual, generational, racial, or bodily perspective. Within this there is also the need for greater reflection and self analysis of our own privileges, with awareness and responsibility.

The same processes we use to refuse misogyny need to be used to criticise racism within our own collectives and individual surroundings, because these are part of the same patriarchal society we are fighting. Asking ourselves in daily practices and not just in theory how we can avoid getting lost in the usual oppression structures that we reproduce. Collaborating with all feminisms and actively listening to what they call on as a solution. Reviewing often who is the protagonist and spokesperson of which story and which struggle.

Understanding that there is no such thing as a universal feminism, does not mean diminishing the importance of making it visible and hegemonic. It means trying to be more active and work more consciously towards a more transnational, inclusive and anti racist feminism that requires acknowledging our own privileges and the position from where we are standing. The feminist movement brings the possibility of opening up a process of creation of alliances and spaces for mutual listening, with the objective of learning and working together not just as equals because we don’t come from the same backgrounds and experiences, but acknowledging our starting position, our privileges and the consequences of our actions.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)