The pretext for this short set of observations is a visit to the newly opened exhibit Poland: Land of Folklore? at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. The compelling, beautifully installed exhibit showcases the Communist-era “branding” of Poland as a modern yet deep-rooted land, a colourful vision of a united, forward-looking Polish peoplehood inspired by tradition. The image was at once ideologically appropriate, nationally celebratory, and globally exportable. From the performance of Poland at international youth gatherings through song and dance, to the patronage, mentoring, and marketing of its handicrafts and design via the institution of a state-run network of Cepelia stores at home and abroad, the exhibit takes a critical look at the whole-cloth invention of a new national imaginary in the early years of Poland’s People’s Republic (PRL).

The colourful array of “folk” products and performances is today a sign of all that was wrong with the previous regime.

All exhibits – even critical ones like those typical for an avant-garde institution like Zachęta – are of course arguments, and as such they betray the preoccupations of their social contexts and historical moments. Despite being a progressive institution, the show partakes in something of the general post-1989 backlash against all things tainted by association with the socialist era. Indeed, as the curator herself points out, the discredited socialist state, the “Polska Republika Ludowa,” held the notion of the “folk” (“Lud”) at the core of its identity. Thus, its colourful array of “folk” products and performances is today a sign of all that was wrong with the previous regime: culture reduced to propaganda, the superficial celebration of the peasantry by urban elites alongside the destruction of their way of life, and the replication of longstanding relations of patronizing inequality while making the accompanying social conflict invisible.

Fascinating and true though this view may be, the introductory text enables the exhibition to answer a broader set of questions – among them how the “people’s” government used folklore, and how its status changed when it moved into museums and galleries in the first decades of the PRL. It also states that the exhibit inquires about the “place of the folk artist – the other – in the art world.” But the breadth of both the exhibition’s exploration of the state’s use of folklore and its inquiry into “otherness” is curiously lacking, in ways that replicate some of the very silences it seeks to critique. Indeed, the curatorial gaze brought to bear on the PRL’s production of “the folk” in Zachęta’s gallery shares some of the same blind spots with the “countryside as seen by ethnographers” that is the partial subject of the exhibition.

If a key critique of PRL-era cultural production was the exoticisation and instrumental treatment of the peasant-workers it intended to celebrate, these central subjects of interest hardly make an appearance in the gallery. To make sense of their work, we are shown the structures imposed by the state and at times their clear influence (e.g. carpets hand-embroidered with tractors), but with no insight into the human agency that in part determined the outcomes. We get ideology, that is, but not experience. How did the provincial peasants who were being called on to produce “their” culture on an industrial scale react, engage, navigate, and negotiate with their new mandate?

The process by which peasants became and thrived as folk artists is too close to the PRL’s own celebratory narrative.

The best ethnography from the era captures humorous descriptions of rural woodcarvers trying to grasp precisely how to be “folk” enough to please the elites who encouraged and might purchase their works – a bottom up process of “self-folklorisation” catalysed by the state’s top-down version. Where are their voices? It is almost a truism that the new crafts encouraged by the state, and the new forms of artistic production like “design collectives” and academic-rural collaborations, not only imposed on, but also served those entrained to produce the desired “culture.” But how did they do this, and by how much? Beyond potential money or a modicum of fame, what did the new creative language and new aesthetic horizons for expression produce in existential terms? Even in authoritarian settings craftspeople put their personal stamp on what they produce – they make their worlds, even if not under conditions of their choosing. The process by which many peasants became and thrived as folk artists due to state encouragement is perhaps too anxiously close to the PRL’s own celebratory narrative to garner attention in this show. (A small photograph of the original 1966 “Others” exhibit partially replicated in the current exhibit, shows the central place given to the makers of the art on display – however instrumental – in form of life-size photo-banners. The one, fascinating nod in the present exhibit in the direction of acknowledging the artists as actors is the curator’s description of women weavers from Janów, who saw the new, specially-commissioned works they produced for city buyers as “folk”, while they continued to produce items for local use to their own taste).

Jewishness in Polish exhibition spaces

This over-emphasis on state ideology over individual experience re-creates any number of that ideology’s own exclusions, some of which peek through but are left unexplained. But rather than fault only communist-bashing, another silence in the present exhibit offers the opportunity to discuss a pervasive issue in contemporary Polish museology, namely the unspeakableness (to be distinguished from the absence sensu stricto) of the tangle of issues relating to the image and fate of Jews in Polish society.

Polska: Kraj Folkloru? approached its mandate of “presenting the complexity and ambiguity of this cultural phenomenon” by touching on issues of politics and social class, the global contexts of international relations and export markets, and even the nostalgic inspiration of modern art’s aesthetic appropriations. But it was strangely mute on a key category traditionally central to folklore-as-statecraft, namely ethnicity, particularly as the exhibit billed itself as dealing with “how the people’s government made use of [folklore]” as propaganda, and how “decisions were made [about] what is folk and what is not.”

More than simplifying, abstracting, and distracting, the images worked to graft a sense of Polish indigeneity onto foreign soil.

The Herderian idea of nations as homogenous ethnic collectivities possessing their own singular “spirit” or character (as manifested in folklore, dance, music, and arts) stands at the heart of 19th century national ideologies. “Lud,” in other words, equates to “Das Volk” – with all its anti-cosmopolitan, racialist potentialities. Among the seismic changes that Poland underwent in the early postwar years, perhaps the most striking was it having turned from a multicultural nation that had historically been no more than 6o% Polish Catholic, to one in which to be a Pole was an ethnic category synonymous with Catholicism (‘Polak to Katolik’). Poland lost its Jews, Germans, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Roma by way of an unprecedented genocide, followed by a series of ethnic cleansings, and a territorial shift involving hundreds of kilometres and a massive population resettlement. The great violence at the heart of the transformation of both multi-cultural Poland into ethnic Poland, and the former German Schlesien into the Polish “Śląsk” (to take only the exhibit’s prominent example relating to the “Recovered Lands”), was elided by the candy-coloured government-sponsored regional tourism posters on display in the opening gallery. Adorned with flowers and circle-skirted dancers, folklore here served to mask not only social disparities, but also wholesale demographic revolution. More than simplifying, abstracting, and distracting, these images worked to graft a sense of Polish indigeneity onto what was foreign soil.

If dwelling on the traumas of what Poles had suffered, witnessed, or perpetrated during or just after the war clashed with socialist optimism, the disappearance of Jewish neighbours, in particular, was a topic that no institution was keen to touch. Yet wooden sculptures of Jews – sometimes as subjects of Nazi persecution – emerged spontaneously as part of the new folk art canon across the country, as woodworking gave individual carvers means of expressing local and national memories. In the gallery that re-creates Aleksander Jackowski’s 1965 “Inni” (“Others”) exhibit, the curator anachronistically included clips from Andrzej Wajda’s 1978 black-and-white documentary film “Zaproszenie do wnętrza,” featuring German folk art collector Ludwig Zimmerer presenting his collection. The macabre close-ups of sculptures like Zygmunt Skrętowicz’s “Bełżec” cycle of wooden bas-reliefs (płaskorzeźby), depicting naked Jewish women herded into a gas chamber, or Władysław Furgała’s sculpture of Father Maxmillian Kolbe in a death-camp uniform (“pasiak”) surrounded by barbed wire and a Nazi guard, comprise the only suggestion of the constitutive violence underlying the very notion of “Lud” and its origins in “Das Volk”. The short film clip points to less colourful aspects of “otherness” that bled through cracks in state-sponsored cultural programs.

But why does the reproduction of the post-war socialist state’s narrow, sanitized framing of folklore by critical 21st century curators produce a sense of muteness? Zachęta visitors’ are given no tools to understand (or even notice) either PRL folklore’s monoethnicity, or the presence of both Jews and racialist violence that the exhibit subtly includes. It is as if both during the PRL and today, privileging the top-down voice of ideology allows cultural elites to avoid dealing with difficult topics that inevitably bubble up from below. Such silences around Jewishness can be found in many exhibitions treating Polish cultural history, where Jewish material may be present (by dint of its sheer inextricability). But it is un-, under-, or misinterpreted, leaving its unsettling resonances potentially readable (by an informed viewer) but seemingly publicly unspeakable.

The works imagined and destroyed riches in the attempt to express “Polish fantasies” during the transition to capitalism.

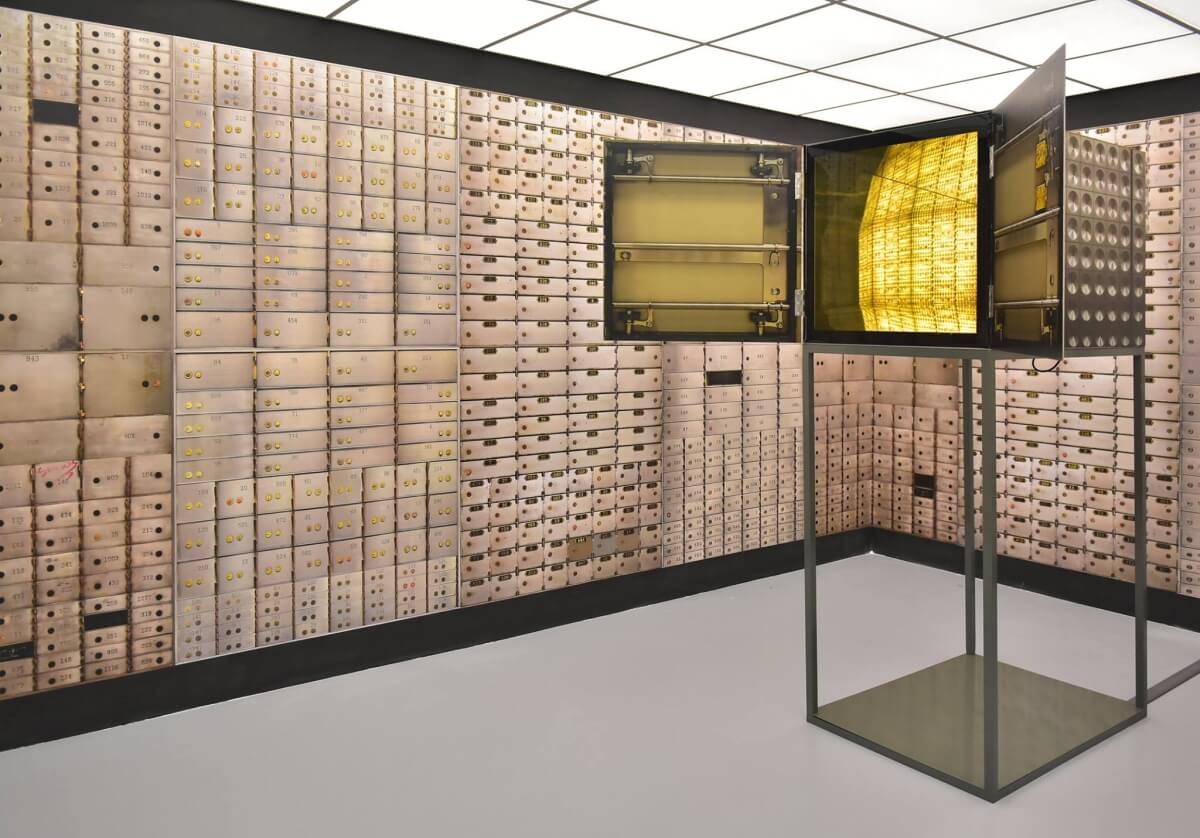

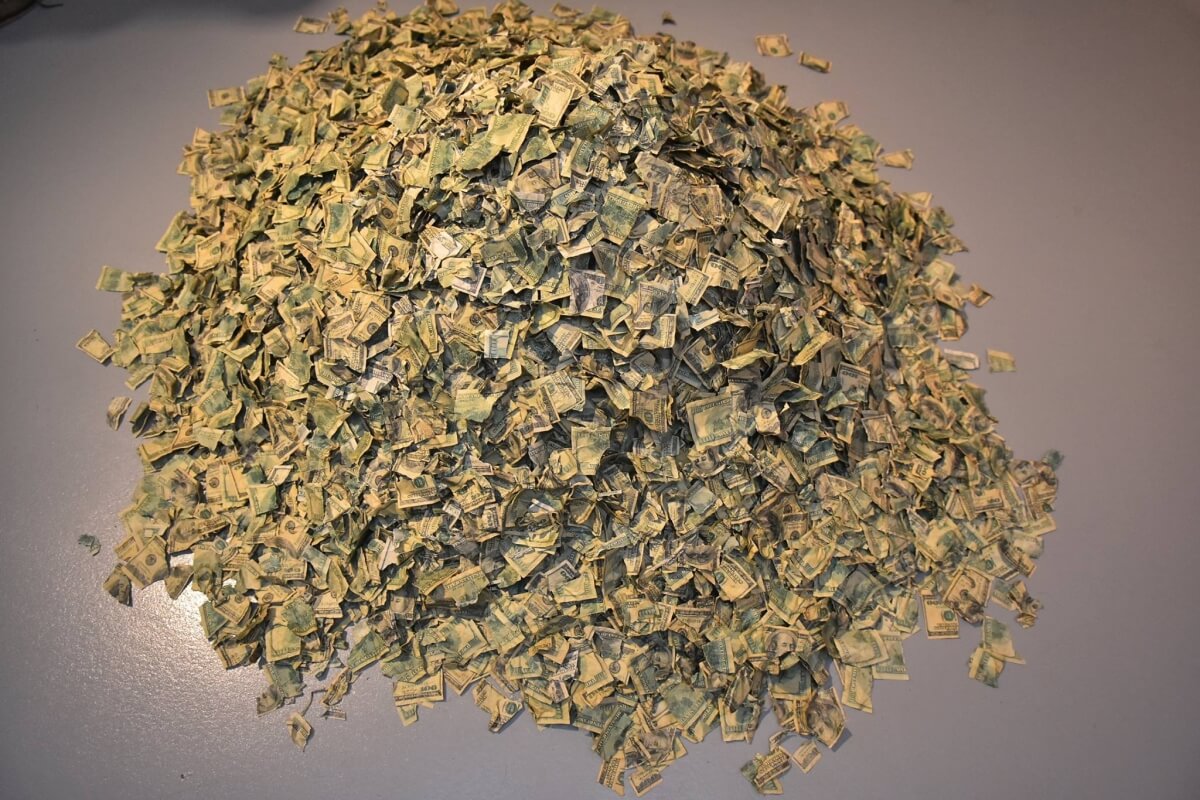

Leaving the Kraj Folkloru? exhibit, I decided to pop into one of Zachęta’s other galleries, and happened to catch the last day of the modern art show Bogatcwo/Money to Burn. Bogactwo featured visual representations, stereotypes, and symbols of wealth from the 1990s through the present that explore the experience of economic shock in a modern Polish culture in which, per the introductory text, “there has been very little affirmation of economic success or career as a life goal.” The cavernous rooms were filled with an array of shiny objects and bling-y slogans, showing how the “best” of the West was seen — alternately yearned for and despised by Poles. There were piles of chunky faux-gold chains served up turkey-dinner-style under glass, ceiling high black wallpaper repeating Gucci-like currency symbols in gold type, a cardboard version of a sports car, a room wallpapered with floor-to-ceiling photographs to replicate standing inside a bank safe, a striking pink-and-black slogan proclaiming “I want it all” (“Daj mi wszystk0”), and a massive “kebab” of Polish amber, waiting to be sliced off of its revolving skewer. The works imagined, grasped for, counterfeited, and destroyed riches in their attempt to express “Polish fantasies and notions of wealth” during the country’s transition to capitalism.

Yet one of the most interesting, and uniquely Polish cultural products of the period in question – and one I fully expected to find in this show where modern art approaches engage with “ethnographic” objects like Piotr Uklański’s first American dollar – is the proliferation of so-called “Żydki”: Jews holding coins or counting money, rendered in figurine or portrait (obrazek) form. Standing next to cash registers in shops, gas stations, and restaurants across the country, they are the consummate visual representation of what the exhibit’s curators call “Polish fantasies and notions of wealth.” Such “Żydki” are both an authentic folk tradition (accompanied by ritual practices that ensure their power to attract funds) connected to the ruralisation of cities mentioned in Kraj Folkloru?, and perhaps also a traumatic after-effect of what philosopher Andrzej Leder called Poland’s “slept-through” socioeconomic revolution in which ethnic Poles stepped into the space emptied by the country’s murdered Jewish population, the country’s original merchant class. It is hard not to read Jewish absence into Ewa Axelrad’s giant photograph of a gold tooth, which echoes Jan Gross’s detailing of Polish post-war profiteering from the Jewish genocide in his book Golden Harvest. Yet the suggestion that Jews have figured centrally and problematically in Polish economic fantasies (and realities) appears nowhere in the gallery.

A closer look at museums reveals both stark absences and awkward “otherings” of Jews.

Given the number of significant new museums in Poland dealing with Jewish subject matter it would be preposterous to argue that Polish curating is silent on the theme of Jews. To the contrary, as exemplified by the world-class Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, the Jewish theme is a core component of Poland’s new museological landscape. But a closer look at museums that deal with key narratives of “Polish” history, culture, or art (e.g. the Warsaw Rising Museum; the Ethnographic Museums in Warsaw and Krakow, the National Museum) reveals both stark absences and awkward “otherings” of Jews. This raises the question of whether the “boom” in Jewish museology may contribute to an unwitting new ghettoization of Jews, recreating a situation where both curators and publics assume that Jewish material belongs in “their” museums, not in institutions seen as telling “really” Polish stories.

I visited Zachęta with an Israeli friend. Like me, he had Polish Jewish grandparents, and has been drawn back to the country in recent years out of a desire to rediscover our ancestral places in this society. The galleries’ absences and silences were obvious to us. As I tell my students, museums are democratized largely from the outside, in claims, complaints, and incursions by members of those groups whose cultures have often been either absent from or (mis-)represented by members of dominant cultural groups. In pluralist societies in the West it has been the activism of Aboriginal “source communities” or marginalized minority groups like African-Americans or British Blacks that have led the most profound innovations in the last thirty years. In Poland the pluralising gaze has not reached a confident critical mass. I am reminded once again of the creative vision embodied in Sławomir Sierakowski’s speech from the collaborative film co-production Mary Koszmary undertaken with Israeli artist Yael Bartana – a work that was also shown at Zachęta in 2011 – in which he called for Jews to return to Poland. Because “with one culture, we cannot see.”

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)